From December 20 to 28, 1943, the Canadian Army experienced its “little Stalingrad” in Ortona, Italy. Famous for its strategic impact, the Battle of Ortona remains one of the Canadian Army’s greatest victories of the war, albeit at terrible cost.

After a successful campaign in Sicily from July 9 to August 17, 1943, the Allies landed in Italy with the aim of finally dislodging the Axis forces and overthrowing the regime of dictator Benito Mussolini. On September 3, the Canadian Army was deployed alongside British troops in the subsequent operations in the east of the peninsula. Indeed, throughout the autumn, Canadian soldiers fought their way up the country, racking up victory after victory – most notably at Campobasso.

The Battle of Ortona was the culmination of the Moro River Campaign, which ran from December 4 to January 4, 1944. The overall aim of the campaign was to break through the German defensive lines and eventually reach Rome, the Italian capital. Ortona is an important strategic position, thanks to its position among the German defenses. What’s more, its port had the potential to offer interesting access for the Allies. So, when the Canadian Army was tasked with capturing the town, the entire 1st Infantry Division was mobilized.

The drive into town

The Canadian Army has been making a lot of mileage in the Italian peninsula, since their landings at the tip of the “boot”, in Reggio Calabria. Italy is a country dotted with many rivers that cross its territory from one end to the other. Thus, these rivers provided ideal fortifications for Fascist and Nazi troops. As a result, the Allies encountered increasingly fierce enemy defenses as they pushed northwards. In fact, when the Canadian, British and Indian armies attempted to reach Ortona via the Moro River, they encountered a particularly difficult and dangerous route.

The German defense line at the Moro River was extended over several kilometers, and the Allies launched assaults on various important points. On December 6, Canadian troops attacked Villa Rogatti, San Leonardo and San Donato, with the aim of crossing the river and forming a bridgehead. Success was variable: the regiments they sent succeeded in capturing a few positions, but the German counterattack was intense and forced the Canadians to alter their plans.

The initial plan having failed, Canadian, New Zealand and Indian units renewed their attacks around the river until December 9, opening up a passage for tanks. Over the following days, the Allies crossed the river and tried to secure the other bank.

One of the obstacles before Ortona was a ravine fortified by the Germans near San Leonardo: the Gully. In order to succeed, the Canadian troops spent several days crossing the ravine. On December 14, the Allied General Staff decided that the best course of action would be to take the German defenses from the rear through the village of Casa Berardi. Supported by the tanks of the Ontario Regiment, the Royal 22e Régiment was tasked with capturing the village and forcing the enemy to retreat. Capturing the village was much more difficult than expected, however. Despite the support of Allied artillery and tanks, the German soldiers were well entrenched and did terrible damage to the members of the 22nd. Officer Paul Triquet persisted, however, and continued his charge until he reached his objective: the Casa Berardi manor house. From there, Triquet mobilized his troops and held his position in the face of enemy counter-attacks.

Victory at Casa Berardi enabled the Allies to capture the ravine preventing them from advancing any further. Shortly afterwards, the main objective was revealed: the town of Ortona.

The Battle

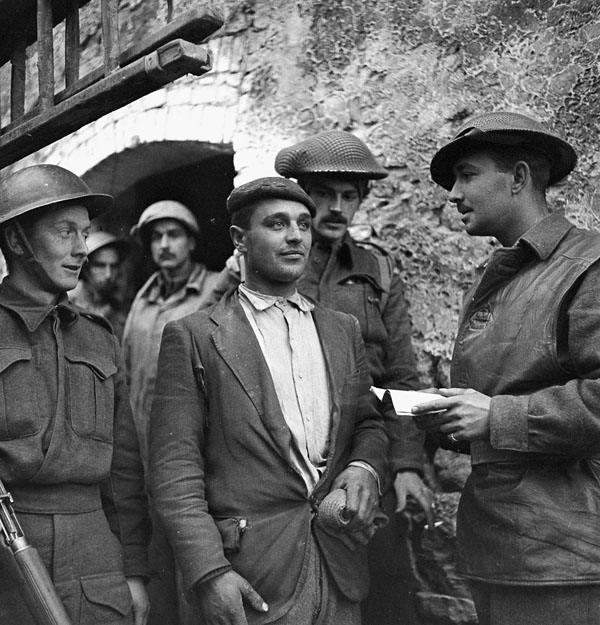

After intense fighting on the banks of the Moro River, the Canadian army finally entered the town of Ortona on December 20, where the hardest part was yet to come. The 1st Fallschirmjäger-Division, the German 1st Parachute Division, was responsible for defending the town from Canadian troops. While the latter had already built up some combat experience since the Sicilian campaign, they were not as experienced as the German division, which had fought all over Europe: in Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece and the Soviet Union. Nor are the paratroopers strangers to violence, having already accumulated several horrific war crimes against Italian civilians since their mobilization.

The fighting in Ortona was particularly brutal. In anticipation of the Allies’ arrival, German defenders booby-trapped every corner of the town with mines, grenades, machine guns and snipers. The aim is to slow and bog down the Canadian advance as much as possible. Using the streets to advance into the city was therefore impossible. The Canadian soldiers thus opted for an innovative urban combat tactic: mouse-holing.

Mouse-holing involves using explosives to force passages between the walls of adjacent buildings. Once part of the wall has been demolished, soldiers then throw grenades to secure the area from any enemies. Devastating tactics, however, come with their share of risks as they force soldiers into close combat in very restricted areas or on different floors. Not to mention the collateral risks to civilians sheltering in the city!

As stated in a report written years after the battle, the art of urban combat is sometimes mastered the hard way. Despite their years of training in Britain, Canadian soldiers were not trained for such an urban battle. In fact, in addition to mouse-holing, their methods of dislodging the Germans were developed on the spot, as the fighting raged on. After a week of fierce house-to-house fighting, the Germans decided to leave the city. The Canadians were victorious on December 28, 1943.

Above: On December 27, Officer Roy Boyd of C Company, Loyal Edmonton Regiment, was buried under ruins in Ortona, where he remained for more than three days. He was finally found and rescued on the 30th (source: Library and Archives Canada).

Ernest “Smokey” Smith (1914-2005)

Born in British Columbia, Ernest Smith enlisted in the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada in 1940 to try and make a living. It was in Sicily that Smokey saw his first action, as his regiment fought at Leonforte, Agira and Regalbuto, among other places. In Italy, Smokey took part in the fighting around the Savio River at the end of October 1944. During a German counter-attack on October 22, Smokey mobilized his colleagues and single-handedly took down a tank and several soldiers, while protecting the life of one of his wounded comrades. For his actions, Smokey was awarded the Victoria Cross. Listen to what he has to say about the battle of Ortona:

Conclusion

In total, the Canadian Army suffered 2,339 casualties (1,375 killed and 964 wounded) during the fighting around the Moro River and in the Battle of Ortona. The battle was also disastrous in terms of civilian casualties, with 1,314 Italians killed. The city of Ortona was completely destroyed in the aftermath of the fighting, as mouse-holing may have been an effective military tactic, it was also a very destructive one! During the war, the town served as a stopover for the Allies before continuing the campaign further afield. However, it took several years before the city was completely rebuilt.

After the battle, many reports were written assessing the Canadians’ performance and the different strategies adopted. Indeed, at this point in the war, Ortona was the largest Canadian engagement that also ended in victory. In fact, Ortona became widely studied by the Canadian military years later to assess its contributions to organization, communication, troop movement and weaponry, among others. Ortona’s capture exacted a heavy toll in human lives, but became a formative experience for the Canadian Army.

Cover photo: Lance Corporal E.A. Harris of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment fires on Germans at Ortona, December 21, 1943 (source: Library and Archives Canada).

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. To find out more about the battle of Ortona and the experiences of Canadian soldiers during it, we recommend Catherine Dion-Gagnon‘s article, which recounts the story of her great-uncle Gérard Pelletier, who passed away there.

Sources:

- “Battle of Ortona“, L’Encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “Christmas in Ortona“, Gouvernement du Canada/Government of Canada.

- “Christmas in Ortone“, Valour Canada.

- “Mouse Holes in Italy“, Valour Canada.

- “Sergeant (Ret’d) Ernest “Smokey” Smith, VC“, Gouvernement du Canada/Government of Canada.

- “The Battle of Ortona“, Liberation Route Europe.

- ““Smokey” Smith, V.C.“, Valour Canada.

This article was published as part of our exhibition on the Italian Campaign: Through Vines and Mines. Visit our exhibition to learn more about the history of the Canadian soldiers and nurses sent to Italy!