LIFE AFTER THE WAR

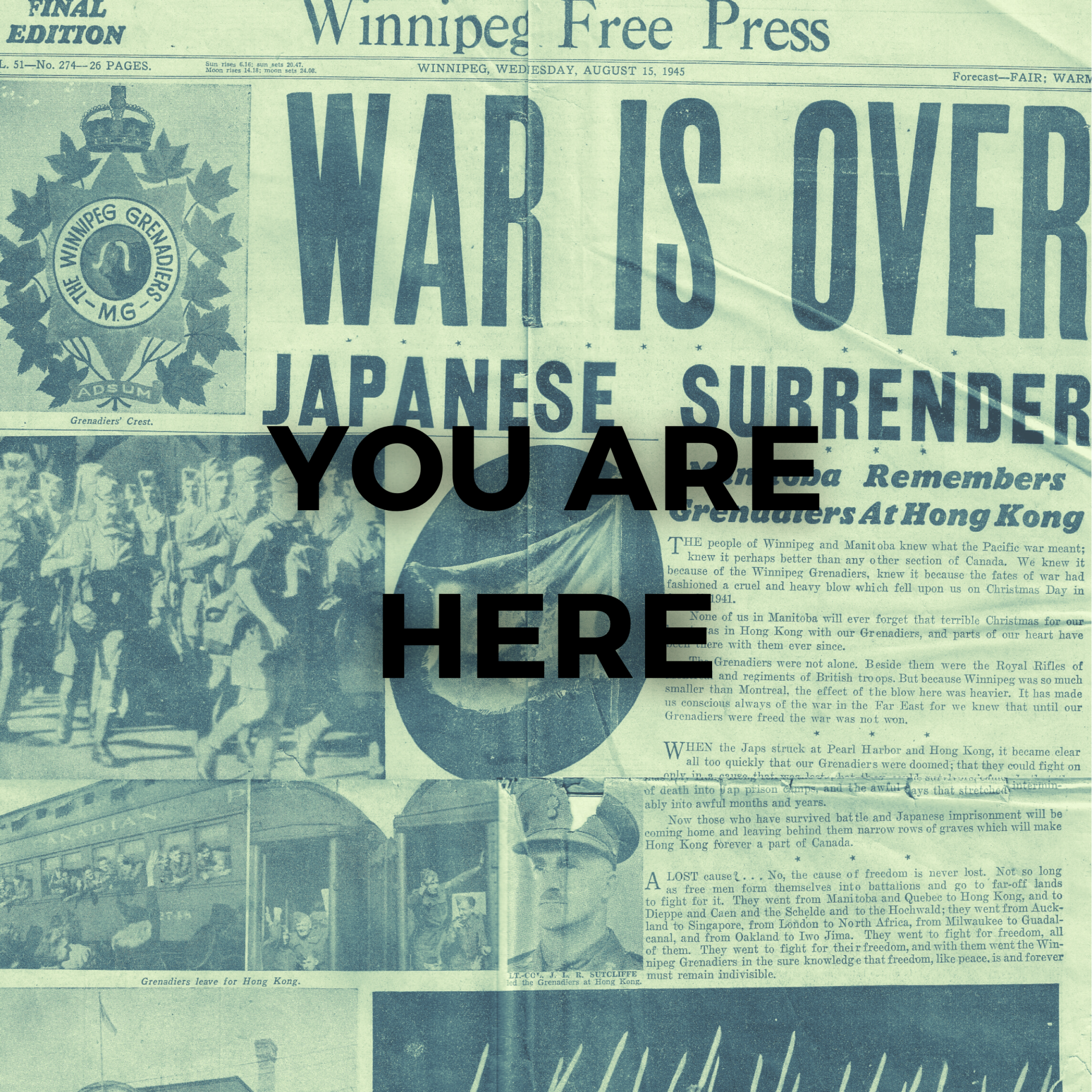

JAPAN SURRENDERS

The American army advanced rapidly on the Japanese positions. In 1945, Japan’s army was pushed back into its archipelago, and the Allies massively bombed the country’s main cities. This operation culminated in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the beginning of August, a show of force that convinced Japan to surrender a few days later on August 15th. Their capitulation was officially signed on September 2nd.

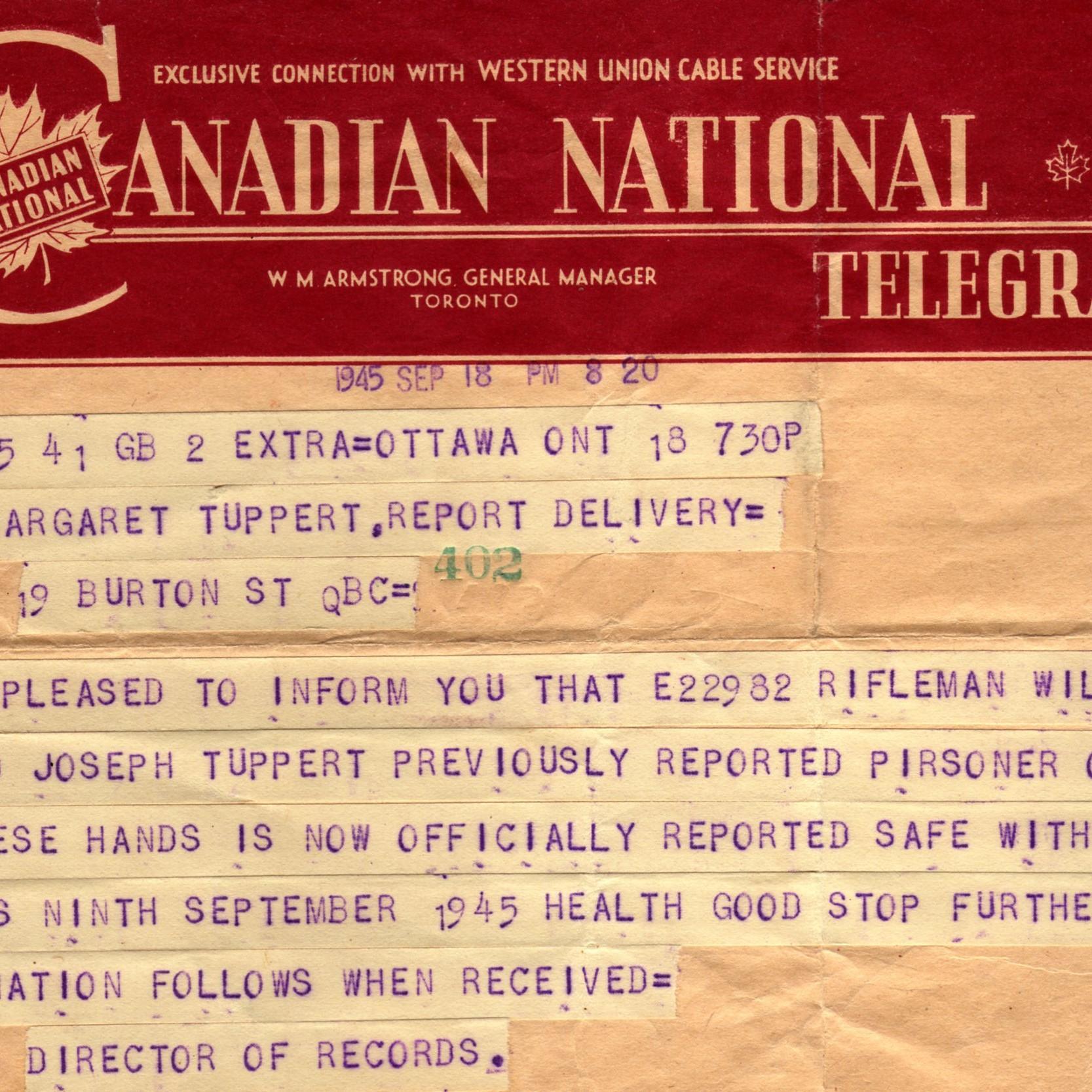

Starting in 1944, the prisoners started seeing many signs that the war was coming to an end. At the camps, many Canadians reported seeing American aircraft, which indicated the proximity of the U.S. Navy to their positions. In Japan, civilian internees, who were put with the military prisoners in the labour camps, started looking like “walking ghosts” according to Rifleman William Tuppert.

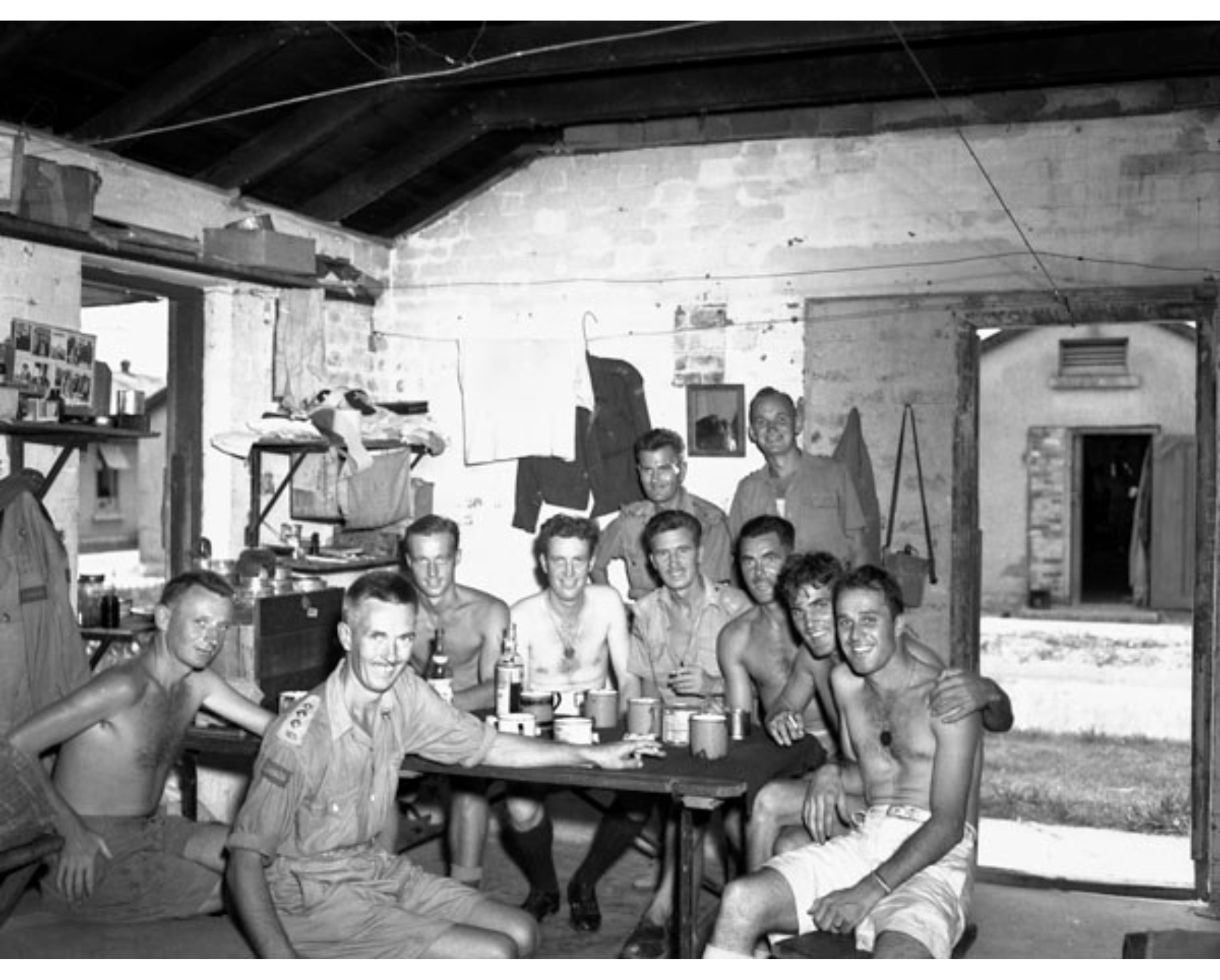

The prisoners were quickly informed that the war was over and that they would soon be released. Allied aircraft regularly passed over the camps and dropped packages with supplies. The Canadians lived in the camps with some sense of peace until they returned home in September.

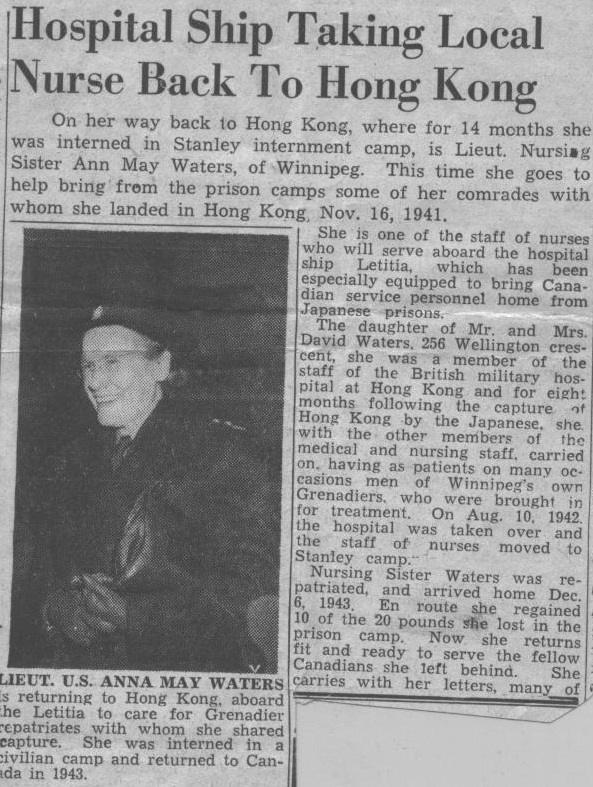

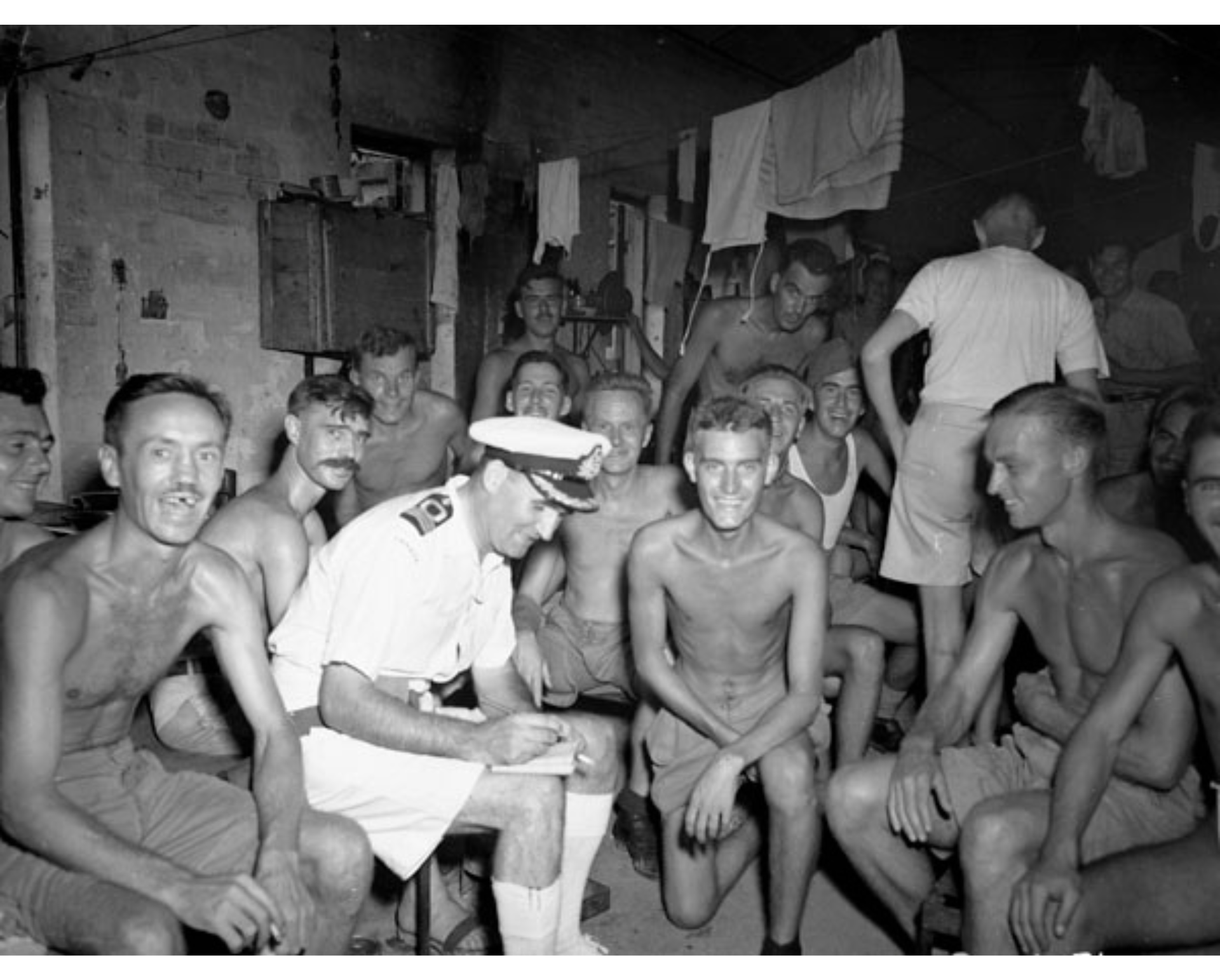

The liberation of the prisoners of war took place gradually, as soon as Japan surrendered. Upon the liberation of the camps, military personnel visited the prisoners in the camps to assess their condition before repatriating them (source: Library and Archives Canada).

BACK HOME

The prisoners began their slow journey home starting in September. Many had to spend long periods in military hospitals in Guam, the Philippines, or San Francisco before returning to Canada. They then arrived in Vancouver, where they could call their families for the first time. The veterans then took the train home and were greeted like heroes at each station. Most were lucky enough to spend Christmas at home with their families, but they then had to report back to the Canadian Army for further hospitalization, as their malnutrition required months of treatment.

Most soldiers returned to Canada with illnesses directly related to the lack of food at the camps. All former prisoners suffered from vitamin deficiencies and had varying degrees of sight problems. Others bore physical scars from battle wounds or from being attacked by guards. Many veterans came back with psychological scars that were never diagnosed. Unemployment, chronic illness, dependency, blindness, and shortened life expectancy were all consequences of the months of abuse, malnutrition and forced labour that would last a lifetime.

WAR CRIMES TRIALS

In keeping with U.S. policy, in 1952 Canada absolved Japan of any responsibility for wartime atrocities. With the rise of communism in Asia and the Cold War becoming a reality, the United States needed Japan to be a reliable ally. The trials of war criminals were therefore governed by politics rather than justice. In Hong Kong, however, the colonial administration held 60 trials against Japanese war criminals. Colonel Esao Tokunaga, who was in charge of all camps in Hong Kong, was arrested and sentenced to death.

REPARATIONS

Hong Kong veterans fought for a long time to receive reparations for the conditions of their incarceration. It was not until December 11, 1998, that the Canadian government agreed to compensate the victims with approximately $24,000 each. On December 8, 2011, 70 years after the battle, Japan formally apologized to the Canadian POWs but did not offer any financial compensation.

KEEPING THEIR MEMORY ALIVE

Out of the 1,975 Canadians who left in October 1941, about 550 never returned home: nearly 290 fell in battle, and about 260 died at the prison camps. Most of the fallen are buried at the Sai Wan War Cemetery in Hong Kong; 137 others, most of whom died in captivity, are buried in the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Yokohama. All physical evidence of the fighting is gone, and most of the camps have been demolished.

Canadian troops who helped defend Hong Kong have been honoured in different ways. Many received medals and awards. In 2015, China even gave Canadian veterans a medal to recognize their combat contributions. In Ottawa, a memorial wall in their honour is engraved with the names of all members of “C” Force: the 1,973 soldiers, the two military nursing sisters, and even the dog Gander. Although these two regiments no longer exist, their memory remains alive.

Photo #1: The Sai Wan Military Cemetery in Hong Kong was erected in 1946 in memory of the Allied soldiers who died in battle and in prisoner of war camps. The Cross of Sacrifice aims to honour Canadian soldiers (source: Canadian War Museum).

Photo #2: Graves of Canadian soldiers buried at Sai Wan Cemetery (source: Canadian War Museum).

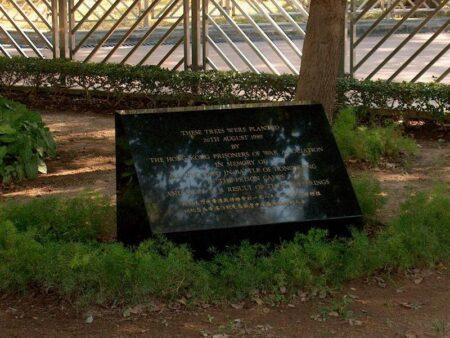

Photo #3: One of the two commemorative plaques placed at Sham Shui Po Park. The only trace remaining of the fighting in Hong Kong, this plaque was installed in 1989 by the Hong Kong Prisoners of War Association in honor of the men who died in Hong Kong during the war (source: Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association).