MEANWHILE IN CANADA

THE KING GOVERNMENT IS CRITICIZED

The news of the defeat made waves in Canada. Criticism was rife: many condemned the high cost in men and their lack of combat experience. The Conservative Party accused Mackenzie King’s government of neglecting the training of soldiers and argued against further Canadian military participation in the war, stating that “perhaps there will be more Hong Kongs.” The newspapers called “C” Force a “suicide squad” and called on the Government to stop sending men to be sacrificed.

THE DUFF

COMMISSION

In response to the criticism, the Canadian government set up a commission to study the circumstances of how the two regiments were sent to Hong Kong. Tabled in 1942, the report concluded that Canada had made a sound decision in their choice of the two regiments and that there was no negligence in terms of their training or equipment. While new assessments in 1948 refuted this claim, they concluded that more training and access to more equipment would not have changed the outcome of the battle: “C” Force would never have been able to withstand the Japanese onslaught.

Photo of the Canadian House of Commons taken on September 7, 1939, during the deliberations concerning the declaration of war against Germany. At this point in the war, the Canadian government had not yet declared war on Japan. As soon as Hong Kong was invaded, Prime Minister Mackenzie King declared, over the heads of Parliament, that Canada was now in a state of war against the Japanese Empire. The status was only put on paper when Parliament returned on January 21, 1942 (source : Canadian War Museum).

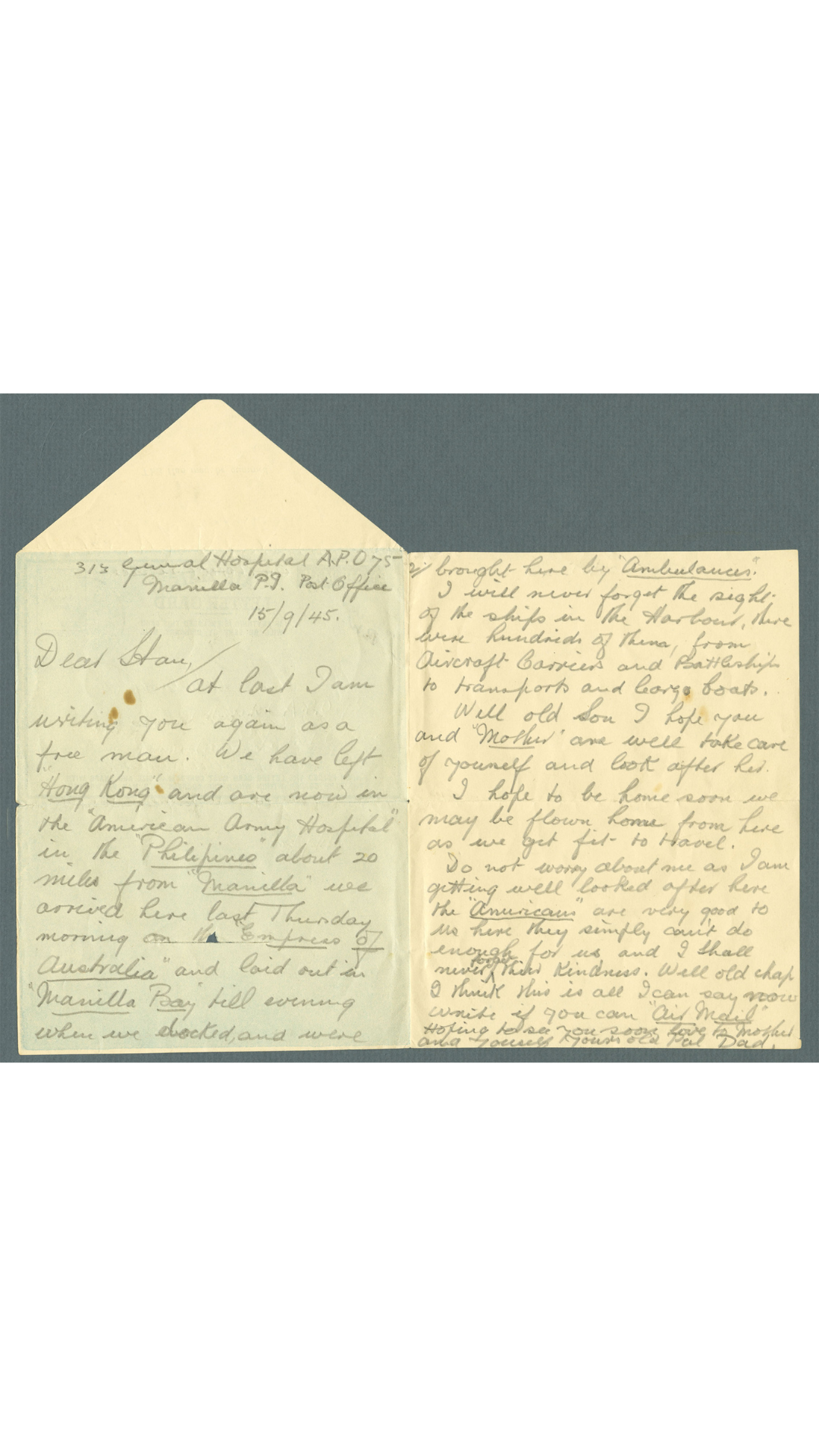

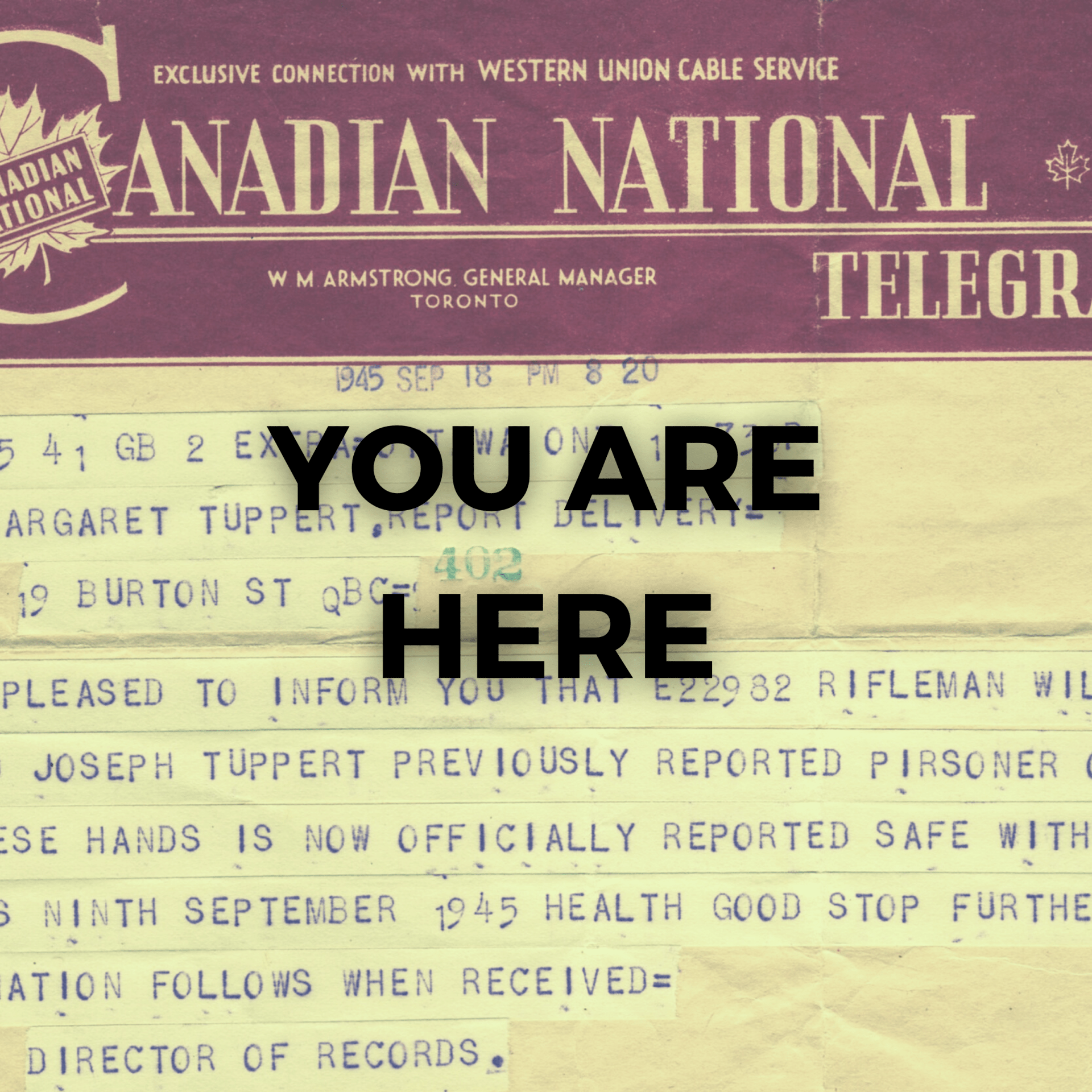

HOW POWs COMMUNICATED WITH THEIR FAMILIES

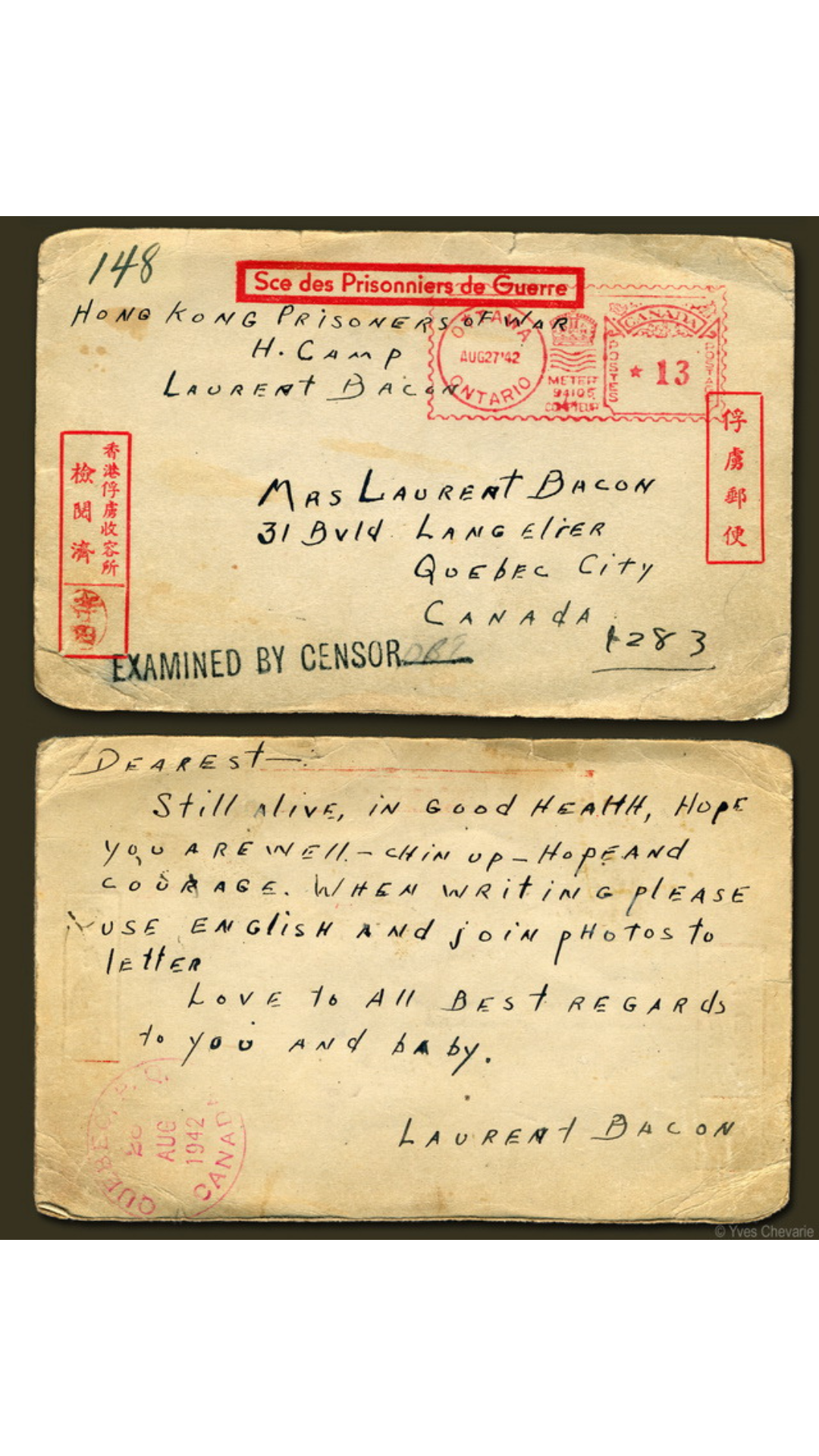

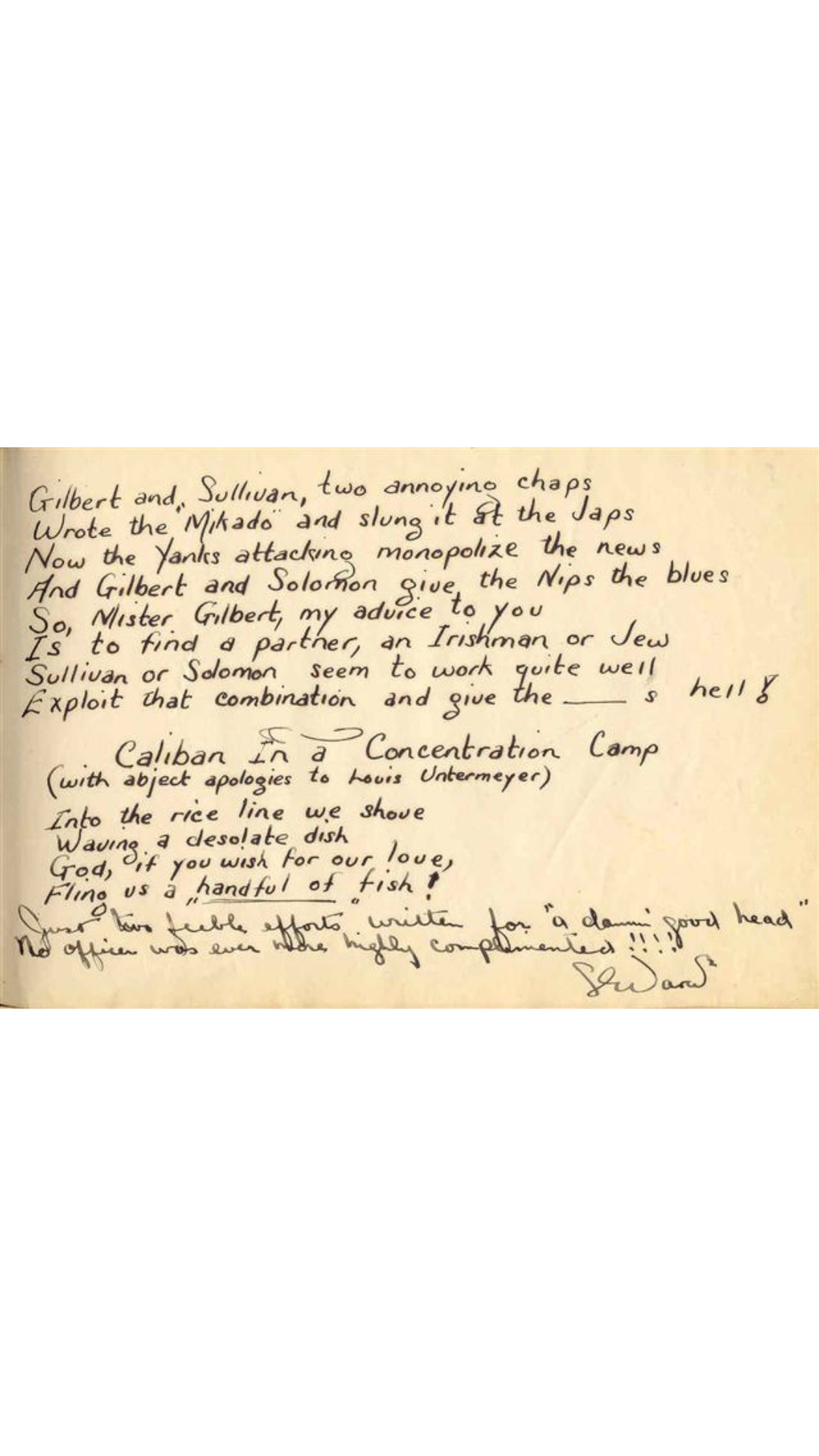

It was difficult for prisoners to get news to their families. The Canadians could send one letter a month, but with many restrictions imposed by the guards. Eventually, prisoners were given pre-printed cards to prevent them from writing letters directly, and they simply had to cross out the incorrect statements. For example, a card might say: “I’m fine… I’m working hard… In the hospital.” Sending and receiving letters was another matter altogether. Letters from Canada took about 14 months to get to the camps, if they were not lost on the way there.

The Japanese censored every letter to ensure the prisoners did not talk about the war or their conditions in the camps. In fact, the letters sent by the prisoners contained few details. Starting in 1942, the Canadian government advised families about what they could write to their imprisoned loved ones. The messages sent to the camps could give news of family and friends, or mention sports. They were of course forbidden to write about politics or the war.

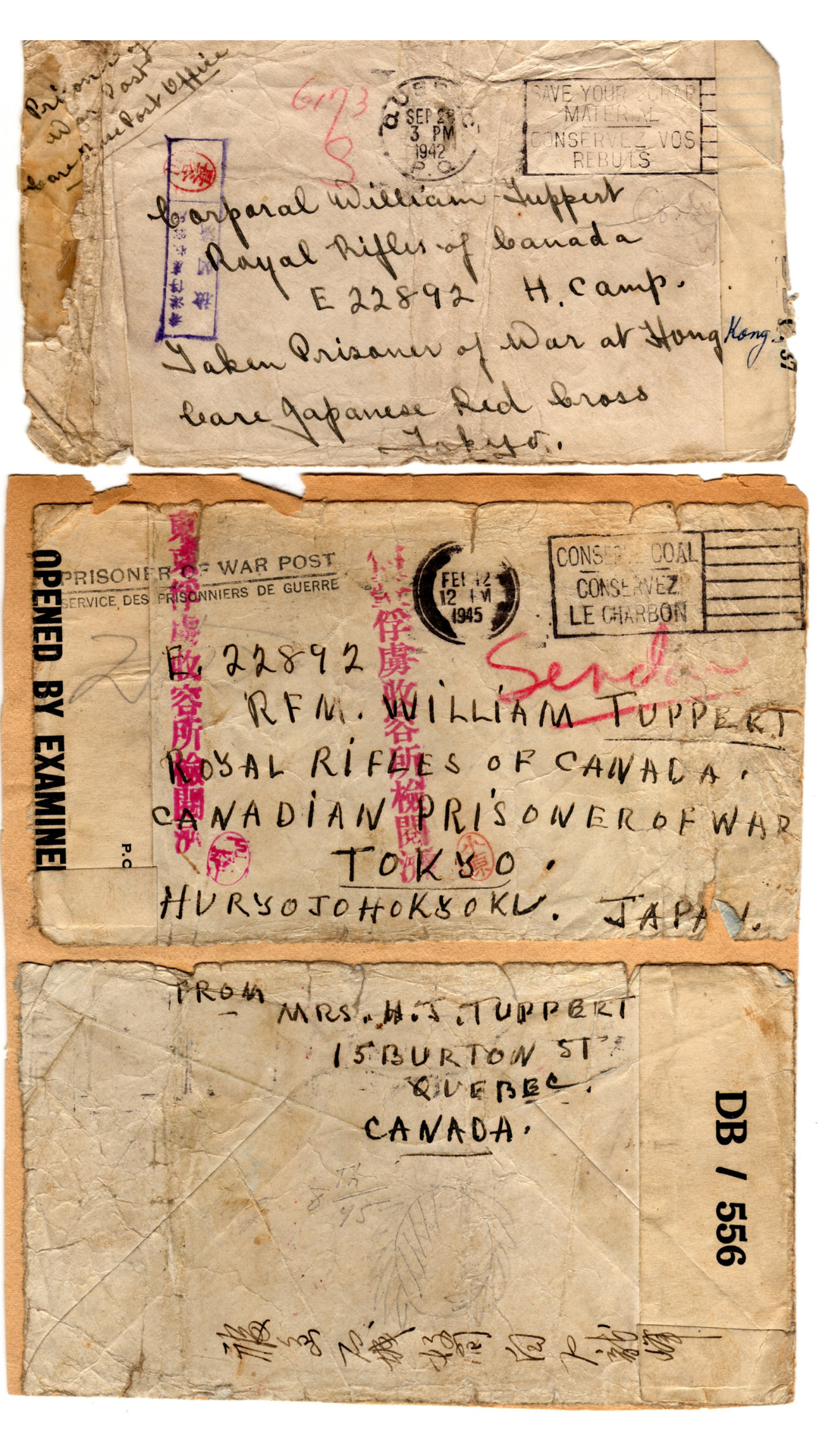

Right: Letters sent by Canadian POWs from the camps to their families. According to the guards’ instructions, the letters were to be very brief and not reveal too many details of daily life in the camps (source: Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association).

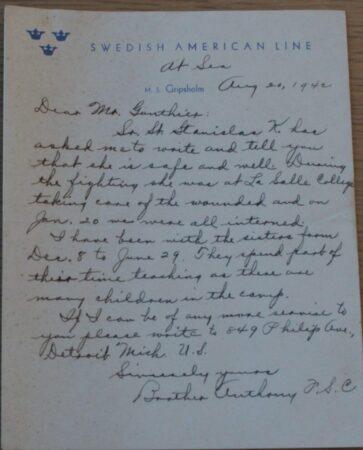

“Dear Mr. Gonthier,

Sr. St. Stanislas K. [Germaine Gonthier] has asked me to write and tell you that she is safe and well. During the fighting she was at La Salle College taking care of the wounded and on Jan. 20 we were all interned.

I have been with the sisters from Dec. 8 to June 29. They spend most of their time teaching as there are many children in the camp.

[…]

Sincerely yours,

Brother Anthony […].”

– Letter adressed to Georges Gonthier, father of Germaine Gonthier, who was interned at Stanley Camp, dated August 20, 1942.

THE INTERNMENT OF

THE JAPANESE CANADIANS

DETENTION

Japanese Canadians have lived in Canada since the late 19th century. After mainly settling in British Columbia, issei (first generation Japanese) and nisei (second generation Japanese) were often subjected to racism. During the war, tensions escalated.

After the Battle of Hong Kong, a wave of xenophobic and unfounded rumours spread against Japanese Canadians, who were portrayed as spies and saboteurs. The Canadian government decided to incarcerate them under the War Measures Act, although the army warned that this detention was unnecessary.

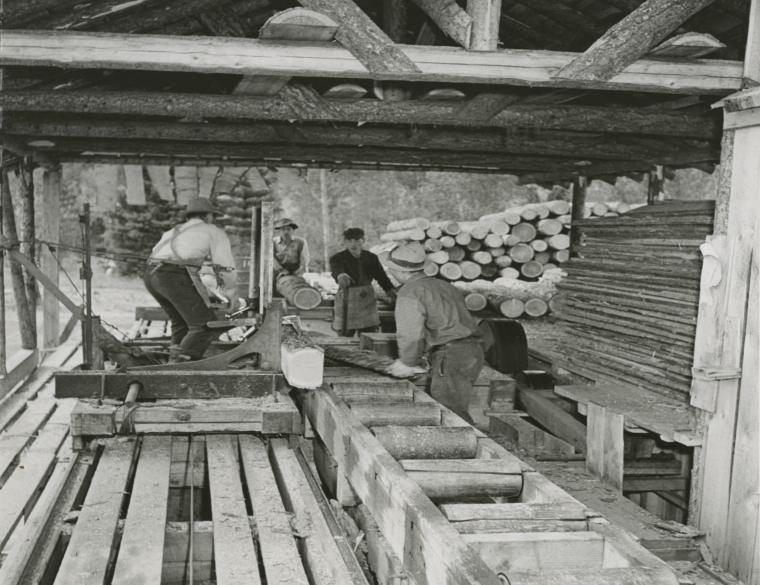

In February 1942, the Government forced the evacuation of all Japanese Canadians from the West Coast and created camps along the highways where the men would be forced to work. They were separated from their families, who were housed in camps set up in old farms and stables.

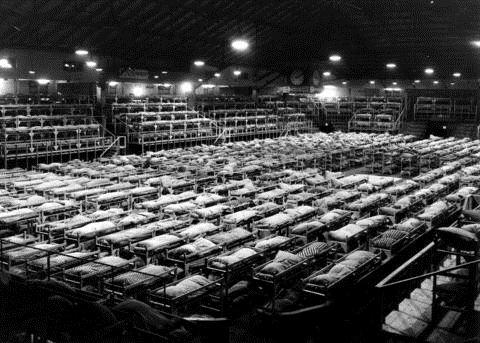

CONDITIONS IN THE CAMPS

After deporting the Japanese Canadians to the camps, the Government seized their property and sold it at very low prices. The prisoners did not get any money from these sales, as the proceeds were placed in government-controlled accounts to pay for their internment. The prisoners had to buy their own clothes, food, and anything else they needed to live at the camps.

The prisoners had to spend their first winter in tents. They later built huts, but these had no insulation to protect against the climate. At some camps, the living conditions were harsh and humiliating: men and women were separated and crammed into stables that still smelled of horses. There was very little space between the bunks and no privacy to speak of. In the first few weeks, they had to use the animal feeding troughs as toilets, and there was no running water.

It took the Government a long time to make reparations to Japanese Canadians after the war. It was not until 1988 that the Government offered a formal apology and financial compensation of $21,000 per victim of the detentions.