MEDICAL AND MENTAL CARE

NURSES

When the war broke out, Canada started recruiting nurses for all three branches of the army for the first time. In those early years, thousands of women were recruited and deployed in Europe to help the troops. The first Canadian nurses arrived in Sicily just days after the start of the invasion, and their numbers only increased during the campaign as the wounded began piling up.

On missions in active combat zones, the nurses had to do extremely dangerous work and therefore had to wear helmets, combat uniforms, and heavy backpacks at all times. However, any place they were deployed could be dangerous. On September 2, 1943, in Catania, Sicily, an enemy shell fell on a hospital and wounded 12 nurses. Two months later, on November 6, the Luftwaffe attacked an Allied convoy and sank the Santa Elena, which was carrying 1,848 soldiers and 101 Canadian nurses. Fortunately, the ship’s passengers were rescued, and the women survived.

In Sicily and Italy, nurses were sent to different field hospitals. These mobile facilities were set up in tents or ruined buildings as close to the front line as possible to take in the wounded. Unfortunately, resources were scarce to treat the many patients. In December 1943 alone, one clinic in Ortona received over 2,000 patients, including 760 serious cases!

Nurses at the front worked long hours to get as many soldiers as possible back on their feet. However, they also found themselves with the unexpected responsibility of providing comfort. For many men, this attention was a great source of solace that helped them overcome even the most serious of injuries. By listening to them, encouraging them, or joking around with them, the nurses at the front made a difficult situation a bit more bearable.

Maxine Llewellyn Bredt: A Canadian in Italy

Maxine Llewellyn Bredt enlisted in the army in January 1944 and was soon sent to the Number 14 Canadian General Hospital in Perugia, Italy. After her unit set up shop in an old tobacco factory, she said, “You just had to make do,” noting that she and her comrades never “[…] complained about it.” Bredt was stationed in Italy until 1945, when she was transferred to Great Britain to a unit for burn victims. This was one of the most difficult experiences of her life. For 43 years, Bredt continued to work with veterans and volunteered at St. Anne’s Hospital. In recognition of her service, she became the face of the Veterans’ Week campaign in 2019 to commemorate the anniversary of the Italian Campaign.

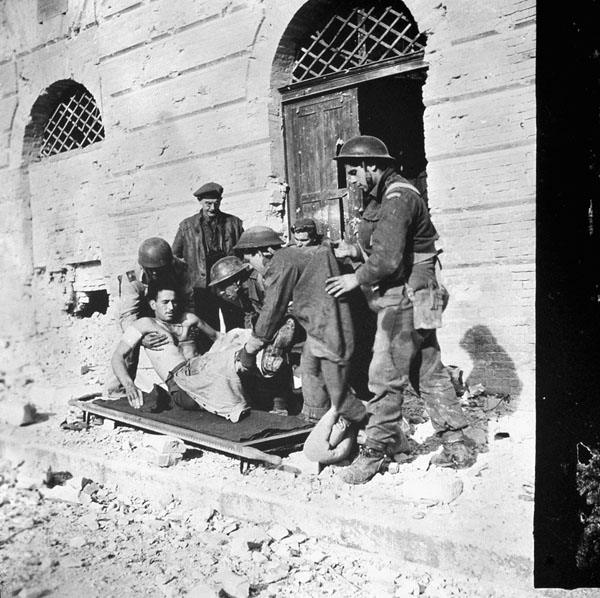

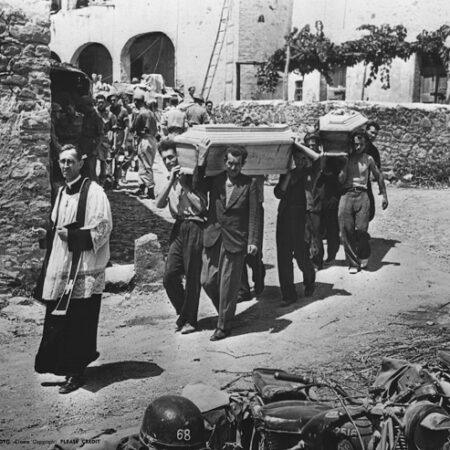

THE PATIENTS

As the campaign wore on, the death and injury toll kept mounting. Overall, the Canadian army suffered over 26,000 casualties, including almost 5,300 fatalities, by the campaign’s end. Since most of the fighting took place in urban centres, the risks of injury were even greater. Buildings were booby-trapped, the roads were blocked, the enemy could hide anywhere, and every bullet and shell could turn into injury-causing shrapnel. For example, during the Battle of Ortona, the Canadian army suffered its greatest casualties, with 1,375 killed and 964 wounded.

The injuries sustained were not just physical ones. While terms such as “battle stress,” “battle fatigue” and “shell shock” were coined as early as the Great War, the effects of combat on the soldiers’ mental health came greatly to the fore during the Italian Campaign. For example, over a three-week period, Canadian army psychiatrist Major Arthur Doyle saw almost 600 patients! However, mental illness was not always taken seriously, despite the intensity of the fighting. The campaign took longer than expected, and the Canadian army constantly needed soldiers at the front. It became customary to send many traumatized soldiers back into battle after just a short respite.

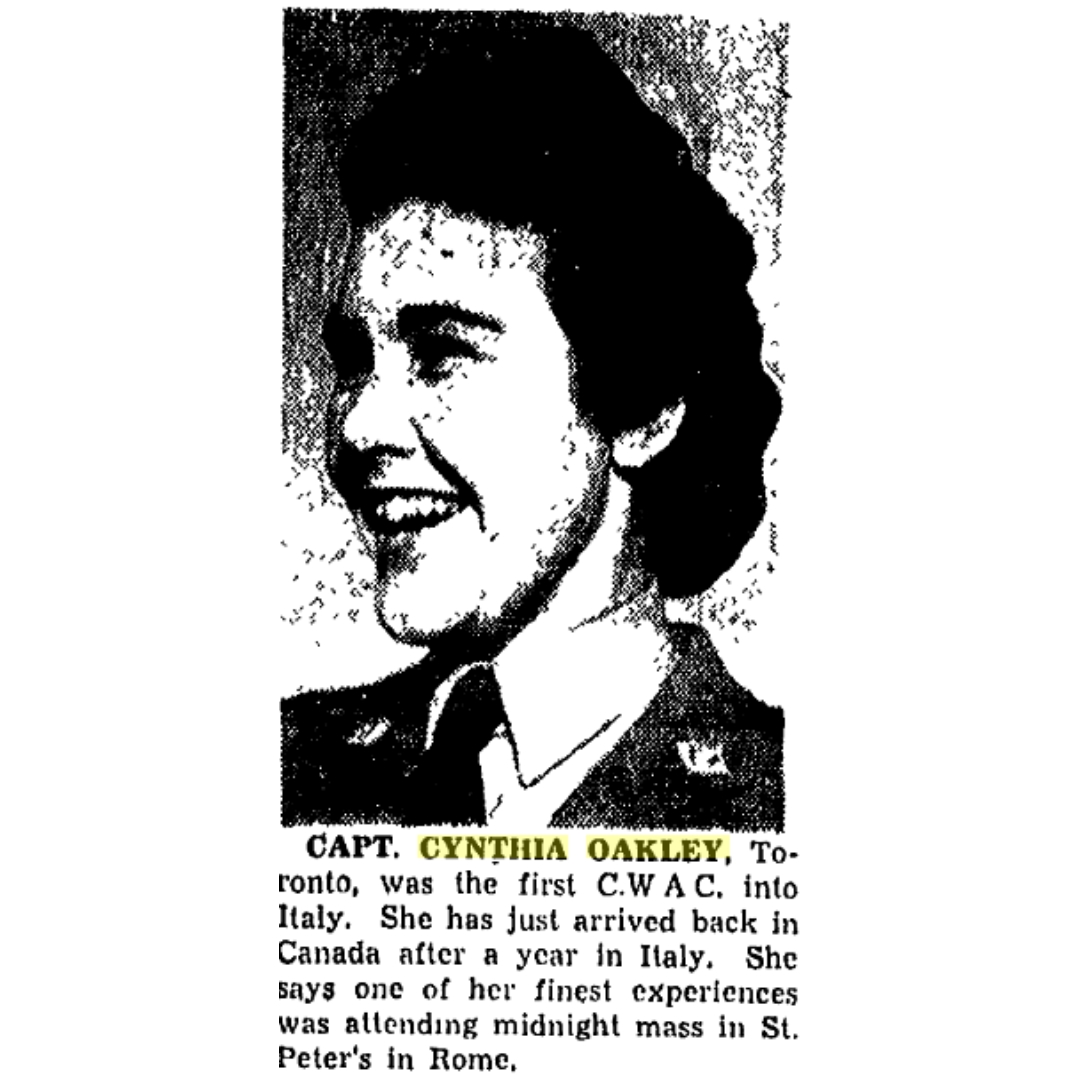

The Canadian Women’s Army Corps

On August 13, 1941, after pressure from women across the country, the Canadian government formed the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) to train Canadian women in a number of auxiliary roles as mechanics, administrators, cooks and performers. Although Canadian women had participated in military campaigns as nurses since the North West Rebellion (1885), this was the first time they were allowed to play a more prominent role in military operations. Women were trained to work in 55 different trades and were often assigned to administrative work or domestic tasks so that men could be sent to the front. The vast majority of the nearly 21,000 women recruited stayed in Canada; however, 3,000 served in England and a few were sent to the front in Europe. The first four women sent to the front to perform in shows organized by the army landed in Italy on May 16, 1943. On June 22, 1944, 39 more women landed in Naples, where they worked in the offices of the Canadian General Staff.

Photo 1 : Des femmes de la base d’entraînement du Service féminin de l’Armée canadienne à Kitchener, Ontario, le 16 avril 1944 (source : Bibliothèque et Archives Canada).

Photo 2: Service members land in Naples (source: Library and Archives Canada).

Photo 3: Cynthia Oakley was one of the few Canadian women to be deployed to Italy during the war. There, she and her group worked on various tasks to support the campaign (source: February 16, 1945 edition of the Toronto Daily Star).

Photo 4: Service members sometimes worked on propaganda projects. Cynthia Oakley’s first task, for example, was to tear down pro-Mussolini posters in Italy. In this photo, we see an exhibition organized in Catania (Sicily) by the United States Office of War Information to present the Allied mission (source : Library of Congress/8d34221).

Photo 5: Some Service members were also entertainers hired to entertain troops at the front. Here, artists get ready in their caravan in Ortona, February 3, 1944 (source: Library and Archives Canada).