THE HOME FRONT

CONSCRIPTION

In June 1940, Mackenzie King’s government passed the National Resources Mobilization Act to legalize the conscription of young men for military service. Derisively called “zombies,” these first conscripts were not allowed to serve outside the country. Instead, they protected Canada’s coasts against a possible German or Japanese invasion. As the war progressed, some thought it unlikely that these soldiers would serve any real purpose.

King hesitated for a long time before allowing the zombies to be sent outside Canada. In April 1942, the Government launched a referendum about opening up the conscription system even more. To appease the two opposing camps of the debate, the Prime Minister then declared “not necessarily conscription, but conscription if necessary.” Across Canada, the population voted overwhelmingly in favour of conscription, with the exception of Quebec, which blamed the federal government for going back on its promises. Conscription was also not unanimously supported in many French-speaking regions of New Brunswick and Ontario or in many German and Ukrainian communities on the prairies.

The Italian Campaign and the invasion of the Normandy beach in September 1944 prompted the Government to extend conscription in November of the same year. The shortage of new troops was particularly acute in Italy, with many wounded or mentally distressed soldiers being sent back into combat almost immediately after receiving care from medical personnel. On the other hand, conscription did not improve conditions at the front, and its contribution to overseas troop numbers was very small, with just under 2,500 soldiers sent to Europe. The conscripts also engaged in riots, desertions and open revolts prior to being sent off.

INTERNMENT OF ITALIANS IN CANADA

After Italy declared war on Canada, the Italian Canadian community was targeted by the Government’s War Measures Act. Mackenzie King’s government designated 31,000 people as “enemy aliens,” or people from a foreign nation deemed a threat to their host country. The Government’s measures were largely discriminatory, as they included all Italian Canadians naturalized since 1922. In fact, Canada began to take action against Italian Canadians on the very day war was declared.

Across the country, many prominent members of the community were suspected of having ties with the Mussolini regime. By this time, the majority of Italian Canadians had abandoned their support for the Mussolini government and saw it as authoritarian and imperialist. Yet many social and community groups maintained superficial ties with the Italian consulate, which added fuel to the Canadian government’s suspicions. In British Columbia, for example, a social club asked its members to sign a declaration of loyalty to Mussolini. For the Canadian authorities, these people represented a potential threat. The same story played out in other parts of the country, and various Casa d’Italia organizations were raided and their members were arrested by the police.

All Italian Canadians considered “enemy aliens” had to report to the authorities every month, but between 600 and 700 of them were interned in camps across Canada. Most Italian Canadians were interned at the Petawawa camp in Ontario, but some were also transferred to the Kananaskis (Alberta) and Fredericton (New Brunswick) camps. Although many internees were released during the war after proving their innocence or receiving clemency, the internment only officially ceased when the war ended in 1945. In 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau officially apologized for the internment of Italian Canadians during the Second World War.

THE WAR ENDS

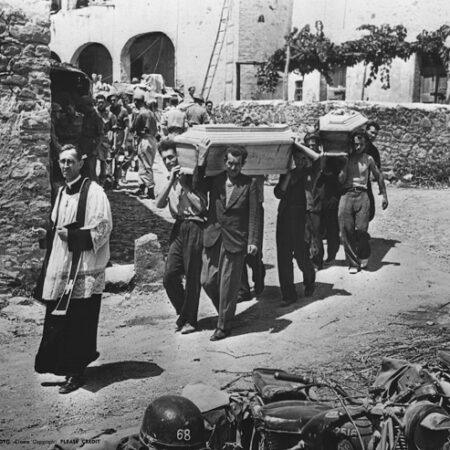

In April 1945, the Allies launched a general offensive against the last remaining troops of the German and Italian armies in the north of the peninsula. At the same time, groups of Italian partisans joined the assault and attacked positions held by the Axis forces. On April 29, following the Brazilian army’s victory at the Battle of Collecchio, the German army officially signed its surrender. This ended the Italian Campaign.

As some historians have noted over the years, the Italian Campaign possibly did not have the hoped-for impacts compared with the efforts deployed. Opened as a second front before a full-scale landing in France, the campaign was always seen by the Allied generals as a diversionary tactic. There is no doubt, however, that this very long campaign had positive impacts and that its effects went beyond simply distracting the enemy army.

For Germany, the start of the campaign was the beginning of the end. This became all the more clear at the end of the campaign when the Mussolini regime was dismantled and the peninsula was liberated. In fact, just one day after the end of the campaign, the Allies had completely surrounded the Nazi regime. A defeated Hitler died by suicide in his bunker on April 30, 1945, and the war in Europe ended almost immediately.

The Ballad of the D-Day Dodgers

The “Ballad of the D-Day Dodgers” is a song written by British soldier Harry Pynn that satirically describes the conditions of the Italian campaign. Since the Normandy landings, many commented that the fighting in Italy was less intense than elsewhere in Europe. In response, the song was sung all over the front line, highlighting the camaraderie of the soldiers mobilized in Italy, their battles, their daily lives and, above all, their losses.