KABUL

The War in Afghanistan, known by many as Operation Enduring Freedom began on October 7, 2001 with American troops landing in Afghanistan. Canada provided support from other bases in the Middle East from the very beginning and Canadian Commandos joined the fight on the ground in December 2001. After only two months, Al-Qaeda had fled to Pakistan and the Taliban was reduced to small pockets of resistance, many having fled to remote areas to regroup and rebuild.

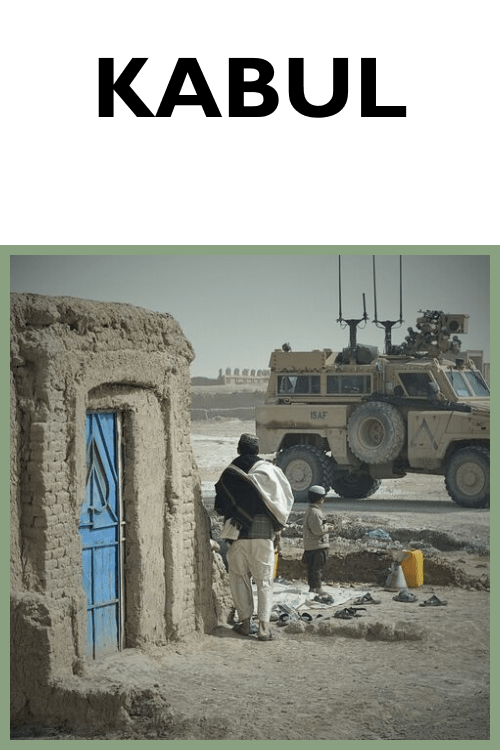

Canadian forces arrived in large numbers in Kabul in 2003 under the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission. Kabul, the capital city of Afghanistan, was much more religiously and socially liberal than most other places in the country, and was far more welcoming to foreign forces than other parts of the country.

An important part of ISAF’s mandate was to assist in the organization of Afghanistan’s first election since the fall of the Taliban. After the initial US-led mission removed the Taliban in 2001, a transitional government was put in place under the leadership of Hamid Karzai. Karzai was then officially elected in 2004. International forces helped to ensure a secure environment and worked with the new government on projects aimed at improving the quality of life in a country that had been devastated by decades of war.

Thus, the mission of the Canadian troops in the early stages of the war was to build stability in Afghanistan. Influence activities were key in this effort.

What is a reservist?

When Canada sent forces over to Afghanistan, it filled each rotation with soldiers from the regular forces, who work full-time for the military. When a regular force unit was deployed, those in the unit were required to go. Some positions, however, remained open due either to the need for specialist or to lack of personnel.

Reservists, who work part-time for the military and usually hold civilian jobs or go to school, could volunteer and apply for these positions. When a reservist was added to a mission, they were called an “augmentee”.

Reservists, therefore, volunteered to serve in Afghanistan. They made up about 20% of the soldiers deployed. Many developed special skills and areas of expertise that helped them qualify for a mission. Reservists were heavily deployed in Influence activities.

Influence activities

Psychological Operations (PSYOPS) is one of the two types of “influence activities,” which are intended to win the “hearts and minds” of the civilian population, and to gain their support. PSYOPS does this through messaging and communications, whereas the other branch of influence activities, CIMIC (Civil-Military Cooperation), does so through concrete actions.

Psychological Operations (PSYOPS)

In Afghanistan, small PSYOPS units were attached to NATO combat battalions. They would work with their battalion to support their needs in combat and would also work to execute their own specific PSYOPS plans and objectives. These units were usually composed of 5 to 6 people, some of whom were tasked with talking to locals and others who watched for and assessed non-verbal cues. They brought their observations back to Headquarters where analysts could create an informed portrait of the needs and interests of the population.

The main communication methods used by PSYOPS were radio broadcast, leaflet distribution (sometimes via air-drops) and face-to-face meetings. PSYOPS teams always kept specific goals in mind when planning their communications.

Long-term support-building programs

In addition to combat support, PSYOPS teams hoped that helping to provide education and promoting democracy would build a basis for long-term stability and support for the Afghan government. They distributed hand-crank radios and provided locals with access to suggested stations, such as local stations where they had contacts and to NATO’s and US forces’ own stations. PSYOPS also developed the Radio Literacy Program which promoted education in rural areas and instilled a positive image of the Afghan government and what it was doing for the country.

Civil-Military Cooperation (CIMIC)

Civil-Military Cooperation (CIMIC) is another type of influence activity. CIMIC units work with local leaders, businesses and non-governmental organizations to build relationships with and provide assistance to the local population.

Building relationships with locals and working on humanitarian aid projects was intended to help the population to better understand the military presence and potentially to see the armed forces as allies. CIMIC teams assess the needs of the local population and how resources can be distributed to both improve the local quality of life and support ISAF’s needs. While in Kabul, Canadian CIMIC teams worked on hundreds of projects. For some projects, contracts were awarded to local businesses to complete the work, thereby creating jobs and forming connections.

Examples of quick impact projects include: building wells and providing access to drinkable water, providing medical supplies to clinics, delivering supplies to schools, repairing roads, implementing sanitation projects, advising on agricultural questions and assisting the local government. Larger development projects provided access to important services for a large number of people and included building roads, fire stations, hospitals and schools. Canada was also developing long-term aims, including improving literacy and access to education, particularly for girls, the eradication of polio, and the completion of a ring road in Afghanistan.