THE END OF THE WAR

AND BEYOND

“The same indomitable spirit which made [Canada] capable of that effort and sacrifice made her equally incapable of accepting at the Peace Conference, in the League of Nations, or elsewhere, a status inferior to that accorded to nations less advanced in their development, less amply endowed in wealth, resources, and population, no more complete in their sovereignty, and far less conspicuous in their sacrifices.”

— Sir Robert Borden

The Treaty of Versailles

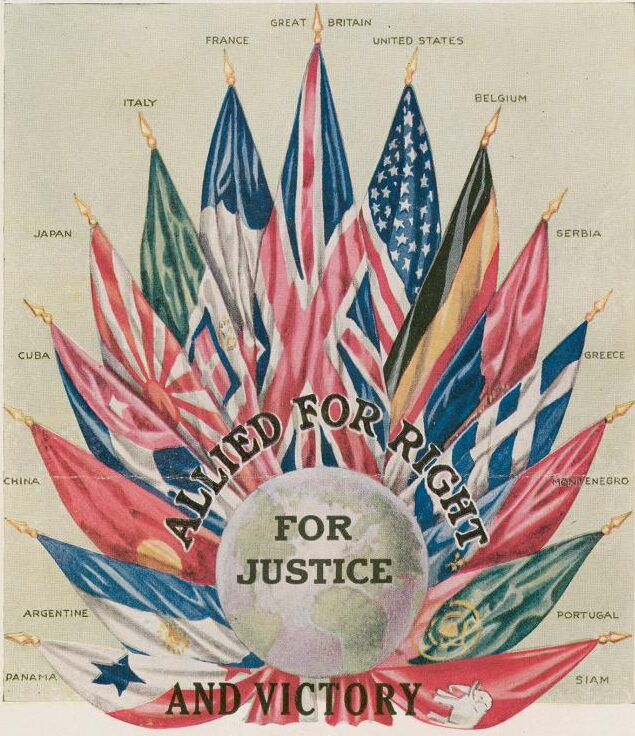

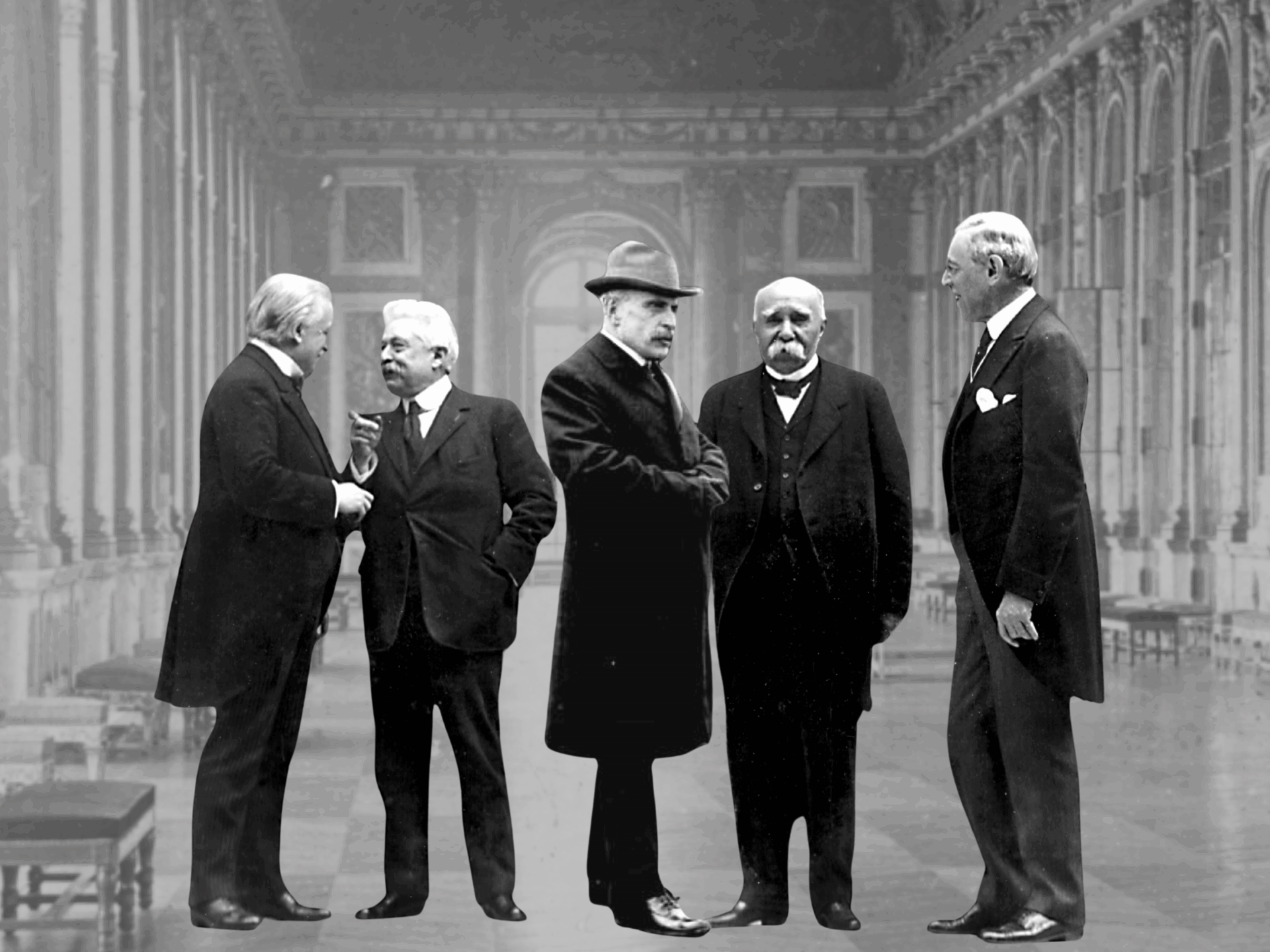

In 1919, Allied leaders and diplomats came together in Paris to negotiate a long-lasting peace. Reflecting a true “world war,” 32 countries were invited to discuss the conditions of peace and to decide a conclusion to the war. The peace treaty was, for the most part, written by the “Big Four”: leaders from the United Kingdom, France, the United States, and Italy. These leaders were joined weekly by the plenary conference, wherein other, smaller nations, including Canada, could give input. Germany was not invited and could not negotiate against the harsh terms imposed by the treaty.

Discover: Use the image to learn about some of the important representatives of the Treaty of Versailles.

(Composite image: Library and Archives Canada/Library of Congress)

Canada’s Coming of Age

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919. The terms of the Treaty of Versailles did not directly impact Canada aside from receiving a small portion of the war indemnities. Because Canada was a Dominion and not a nation independent of the United Kingdom, Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden had to fight to ensure that Canada had representation at the League of Nations and could sign the treaty independently.

Ultimately, the actions of Canadians throughout the war proved to the British Empire and to the rest of the world that Canada, as a nation, deserved to participate in international affairs independently of the British. Canada gained the right to sign the Treaty of Versailles separately from the United Kingdom and was awarded its own seat in the League of Nations, despite the fact that it was still a Dominion of England. For Canada and the other Dominions, these were important steps towards gaining control over their external affairs.

In the years that followed, Canada gained even more independence in its international relations. In 1931 the United Kingdom passed the Statute of Westminster, which officially allowed Canada and the other Dominions to take control of their own foreign policies and to decide independently whether to enter war. When World War II began and Great Britain declared war on Germany, Canada waited one full week before also declaring war, in part to demonstrate that they were joining their own initiative.

New Borders of an Old World

As the war came to an end, many nations had their borders modified. Empires disappeared to make space for more nation states. Victorious nations made territorial gains and the unstable political landscape brought about by the war prompted revolutions and declarations of independence in some parts of Europe.

Discover: Compare the 1914 map of the world (left) with one from 1938 (right). What changed? What stayed the same?

Map Data: Kropelnicki, Jeffrey; Johnson, Grace; Kne, Len; Lindberg, Mark. (2022). Historical National Boundaries. Retrieved from the Data Repository for the University of Minnesota, https://doi.org/10.13020/146x-1412.

A Lasting Legacy

The First World War impacted all aspects of life for Canadians. When the war finally ended, Canadians felt the need to commemorate the immense sacrifices made by citizens across the country. Battlefield tours to France and Belgium began soon after the end of the Great War. People went for many reasons: to find a grave, to accompany a veteran, or simple curiosity. In September 1920 the government created the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission with the purpose of creating war memorials dedicated to Canadians at eight overseas battlefields in France and Belgium. In 1922, the French government gifted 250 acres of land to Canada for the purpose of building one such memorial at Vimy Ridge. Paying tribute to those who gave their lives for their country during the four years of conflict, the monument bears the names of 11,285 Canadians who were killed in France during the conflict and have no known grave.

It took 14 years for architect and sculptor Walter Allward to complete the Vimy monument. The monument was unveiled on July 26th 1936 by King Edward VIII. More than 50,000 veterans and their families from both Canada and France attended the ceremony. The Royal Canadian Legion asked Charlotte Susan Wood, who lost five of her sons in the war, to represent all Canadian mothers who lost a child in the conflict during the pilgrimage. Wearing her Silver cross (a medal given to wives or mothers of deceased soldiers), she laid a wreath at the tomb of the unknown soldier in Westminster Abbey and another at the ceremony at Vimy Ridge. Every year, the Legion continues this tradition by selecting a National Silver Cross mother to lay a wreath on the National War Memorial on Remembrance Day.

The Vimy Oaks

Did you know that while fighting in the battle of Vimy Ridge Lieutenant Leslie Miller collected some acorns from the battlefield and sent them back home to Scarborough for planting? The acorns grew into oak trees now known as the Vimy Oaks. Over 100 years later, the oaks and their seedlings, which are planted throughout Canada and at the Vimy Memorial, act as a living tribute to the sacrifices of Canadians who fought in the battle.

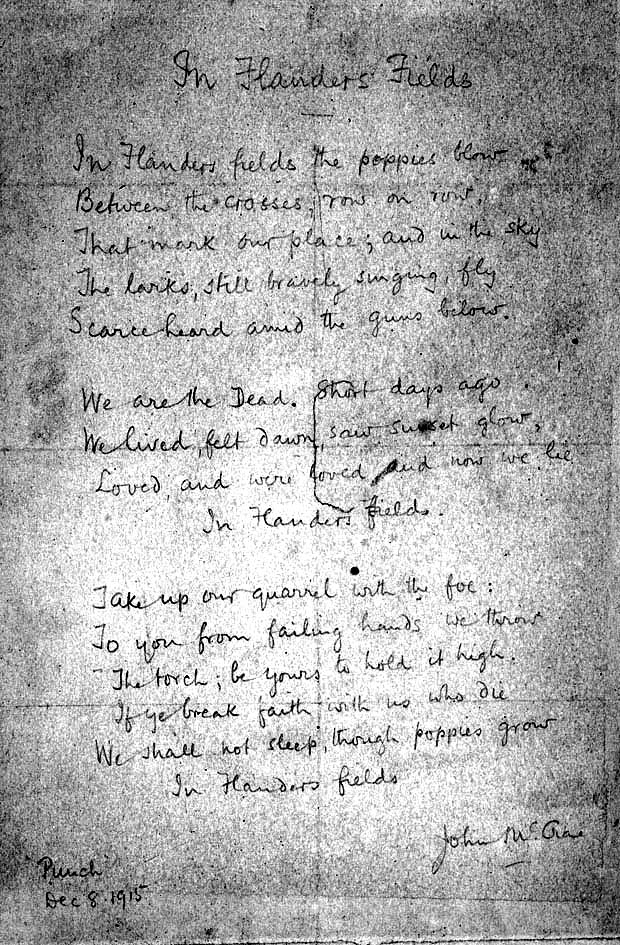

Case Study: How the Poppy became Canada’s Symbol of Remembrance Day

The Historical Significance of The First World War

The impact of the First World War on the lives of Canadians is undeniable. Thousands of Canadians risked their lives overseas to help Britain and its allies. During their service, new medical and technological advancements occurred that continue to help Canadians today. Through their actions in the war, Canadians proved their place on the world stage and earned Canada a name for itself independent of Britain.

On the home front, the war significantly altered the way Canadians lived and worked. Sadly around 66,000 Canadians never returned home from the war, leaving many families without providers. For the military members who were lucky enough to return, they had to reintegrate into a socially and politically transformed society. Canadians rallied together to not only support returned military members, but also families who lost loved ones because of the war. Organizations, including the Canadian National Institute for the Blind and the WarAmps emerged to help returning members of the military and many have since grown to help civilians as well.

Although it occurred over a century ago, the legacy of the First World War continues. Each year over 800,000 individuals pay their respects at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial to honour those who fought during the war. Canadians also continue to honour these individuals on Remembrance Day, held every year on November 11th— the same day that the war ended in 1918.

Think: How did you imagine the First World War before reading the exhibit? Did your views change after?