ON THE FRONT LINES

The young Canadian Army fought in numerous battles throughout the four years the war lasted. While they were victorious in many cases, victory came at the cost of many lives.

Think: Notice the casualties numbered under each battle. What do you think caused such high numbers?

The Battle of Vimy Ridge

Early in 1917, the Canadian Corps was tasked with the capture of Vimy Ridge. Several previous unsuccessful and costly attempts by the French and British Armies proved that Vimy Ridge was well defended by the Germans – who clearly intended to hold onto it.

The Canadians had to apply the lessons learned from their own battle experience and that of their Allies in order to carefully plan an operation that would succeed.

Air reconnaissance helped to locate vital enemy locations. Allied forces largely destroyed German artillery emplacements and trench systems before the arrival of the infantry. This was due to the close coordination between the pilots and the gunners. Preparations for Vimy also included extensive underground excavations. This included placing large amounts of explosives near or beneath the enemy’s position in “mines” at the end of underground tunnels. The plan was to detonate the explosives just before the attack began.The explosions would destroy part of the enemy’s trenches, and allow the attacking troops to rush into the newly-formed gap.

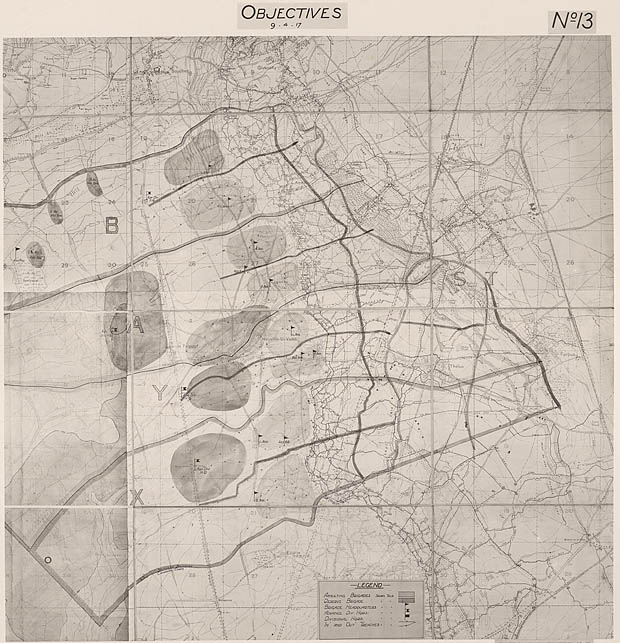

The next step was to have assaulting infantry battalions locate the enemy to better engage them. For the first time ever, all soldiers, not just the officers, received details about their objectives. A total of 40 000 trench maps were printed and distributed to the attacking Canadians. The final preparation was to properly coordinate their artillery and their infantry. A “creeping barrage” was a method of coordinated artillery fire designed to create a “wall of steel” that moved forward slowly at a predictable rate ahead of the advancing troops. Soldiers practiced their timing to perfectly coordinate with the artillery barrage. This rate of advance became known as the “Vimy glide”.

The battle, which lasted from April 9 to the 12th, was a success for the Allies, but 3 598 Canadians gave their lives to take the ridge and nearly 7 000 others were injured. Many Germans also died trying to defend the ridge, suffering approximately 20 000 casualties in total.

Some argue that the Battle of Vimy Ridge was instrumental in the creation of a Canadian identity. Although it was indeed a proud moment for the young Canadian army, this battle did not end the war. In fact, the battle of Vimy Ridge was part of the larger French offensive of 1917, which was in fact a failure.

The true end of the Great War only arrived more than a year and a half after the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

For Lancelot Joseph Bertrand, Vimy Ridge was the first major battle as an officer in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Lancelot enlisted in 1914 and was named Lieutenant in 1916 in part because of his exceptional leadership skills. At Vimy Ridge, all the other officers of his company were killed or wounded. With great determination and courage, he organized his troops and led them to their objective. For his actions at Vimy Ridge, he was awarded the Military Cross in July 1917 and became the first Black Canadian officer to receive a medal for bravery.

Lancelot Joseph Bertrand (Canadian Virtual War Memorial).

November 11, 1918: The Armistice and the End of the First World War

From October to November 11th, 1918, the Canadians and other Allied troops marched steadily forward, liberating Belgium town by town. Eventually, the Germans had to surrender. In the last days of the war, the Canadian troops liberated Mons, Belgium: a town of symbolic importance, as it had been lost by the British at the beginning of the war in 1914.

The Armistice was signed on November 11th, 1918 and at 11:00 am the fighting stopped. It took a further six months to negotiate the Treaty of Versailles.

Sacred Honours

As the dust of war slowly settled, military units celebrated the end of the war and commemorated their fallen.

Even before they demobilized many regiments updated their colours to bolster their pride as a military unit. Regimental colours date from ancient times and serve as a rallying point for soldiers during battle. Today, they mostly serve as a symbol of their regimental identity. Regimental Colours are embroidered and carefully woven by skilled craftsmen and can only be approved by the reigning Monarch.

The Royal Montreal Regiment received their first set of colours in January 1919 at Unter Eschbach, Germany. This was the first time that a Regiment had been presented with Colours on foreign conquered soil at the end of a victorious campaign.

The second regimental flag was officially presented to the 22nd Regiment in March 1921. However, it was not until 1929 that the Regiment received its First World War battle honors. The flag was then sent to England to have the battle honors embroidered on it.

It was also important for the British Empire and the government of Canada to honour their deceased soldiers. Starting in 1919, the government issued Memorial Plaques to the next of kin of all servicemen and servicewomen of the British Empire who died during the Great War or afterwards as a result of their injuries. These plaques were popularly known as the “Dead Man’s Penny”, because of their shape and colour. Each included the name of the individual killed, along with the inscription “[They] died for freedom and honour.” The British Empire issued over 1 355 000 of these bronze memorial plaques from the end of the war until the 1930s.