ON THE HOME FRONT

The First World War did not only affect Canadians who were serving overseas. The war also significantly impacted Canadians at home.

The Economy of War

The First World War was an enormous economic strain on the country. By 1918 the Canadian government was spending over $1 million a day on the war effort. The government also redirected large quantities of resources abroad to help supply the Canadian military and Britain.

Discover: To properly equip the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the military required many resources. Explore the supply box to see some examples of the required resources.

To help alleviate Canada’s economic strain, the government placed taxes on certain commodities, including railway tickets and telegrams. In 1917 they enacted the Income War Tax Act (a precursor to today’s income tax laws). Many patriotic Canadians voluntarily helped support the Canadian economy by buying victory bonds or war saving stamps. The victory bond campaigns raised over $2 billion for the war effort.

Supporting Canadian Farms

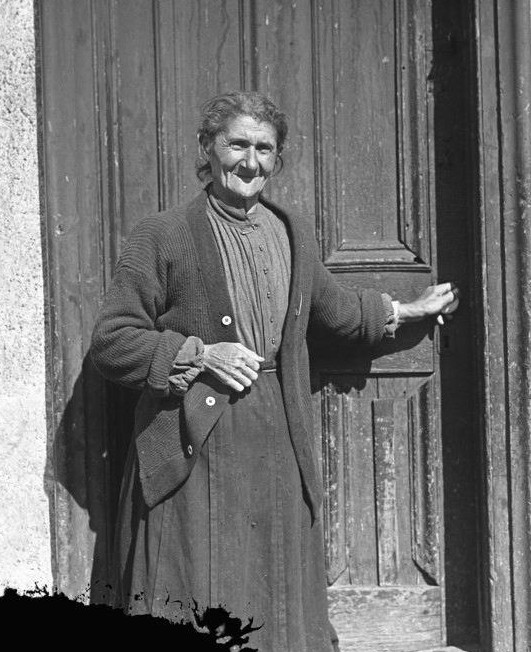

Beginning in 1914, the Government of Canada and provincial governments pledged foodstuffs to the war effort. Farms needed to produce more food to help with the demand, but many farm workers were leaving to fight overseas. Thousands of high school children, who were still too young to fight, stepped up and became part of the Soldiers of the Soil program. This national program sent students from cities to help in farms across the country. In Ontario, many women joined the Farm Service Corps. These “farmerettes” worked on farms, doing everything from picking vegetables to canning fruits.

Rationing also became an important aspect of daily life. Canadians limited their consumption of certain foodstuffs, including red meat, white flour and white sugar in order to ensure that there was enough of these products to send overseas. Many families and local organizations created vegetable gardens, commonly referred to as victory gardens, to help supplement their food supply. As production of wartime goods increased, Canadians also began rationing other commodities including wool, wheat, iron, and coal.

Many Ways to Serve

Many Canadians wanted to aid the war effort but were not eligible to fight overseas. Canadians found many different ways to serve their country at home. For example, some men who were deemed medically unfit to participate in the war overseas could still join the military for home service duty. Others joined local civilian home guard groups. These local guards aimed to protect their communities from potential threats while the military was busy overseas.

Fundraising was another important way for those on the home front to support the war effort. Women’s groups held bazaars and sold homemade products to raise money for military members and their families. Women and children knitted socks, scarves, and other clothes for organizations like the Canadian Field Comforts Commission, who distributed them to military members on the front lines. Other goods, from soap to canned foods, were sent along with the clothing. Sometimes, people even tucked inspirational messages in the packages to keep up the morale of those overseas.

Although there were many war-time organizations across Canada, most of the money raised by Canadians went to one of three organizations: The Patriotic Fund, the Red Cross, and the military branch of the YMCA.

Think: How were these organizations helping the war effort? Why might someone chose to support one over another?

The Patriotic Fund

Toronto Public Library

Spearheaded by Montreal philanthropist and Member of Parliament Sir Herbert Brown Ames, the Patriotic Fund was a private organization that aimed to help the families of Canadians serving overseas. Besides providing financial support, the organization also had volunteers that acted as social workers and provided direct social assistance to these families.

The Red Cross

Toronto Public Library

Founded in 1863, the Red Cross looked after the victims of war (both military and civilian). This included supplying medical aid and supplies to military hospitals, providing care packages to soldiers on the front, and helping civilian refugees. The Red Cross also checked on injured soldiers, brought aid to prisoners of war and searched for information on soldiers missing in action.

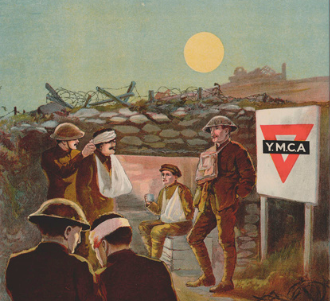

The YMCA

Library and Archives Canada

The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) created its Canadian war service branch in 1866 to help support troops during the Fenian Raids. During the First World War, the YMCA provided spaces overseas for soldiers to rest, learn and enjoy entertainment. The YMCA also organized care packages and gave out stationary so that soldiers could write letters home.

Shifting Roles for Women

The years surrounding the Great War were also a tumultuous time for women. Women began to gain greater economic independence and political opportunities. Legal changes allowed women to own property, control their own finances and sign contracts and wills. Furthering their education became widely possible and many women seized the opportunity to work outside the home.

Snapshots of service

Lois Allen

Farmerette

Biography

Lois Allen was a student at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario when she decided to join the Farm Service Corps in 1918. She was one of 100 women who worked at E.D. Smith and Son’s Jam factory in Winona, Ontario, shucking berries in the spring of 1918. The work at the factory was long and hard. A typical day for Lois and the other farmerettes consisted of ten to twelve hours working at the factory. However, she felt that being a farmerette was a way of “doing her bit”.

Gerald S. Andrews

Soldier of the Soil

Biography

Gerald Smedley Andrews was in Grade 9 at Kelvin Technical High School in Winnipeg, Manitoba when officials came to his school to recruit students as Soldiers of the Soil in 1918. Wanting to serve, but too young to enlist, he took the opportunity. For over five months he worked as a farm labourer at the Grain Family’s farm in Purves, Manitoba. At the end of his service, he received a bronze badge and a certificate of service and good behaviour. During the Second World War he enlisted in the military and worked with the Royal Canadian Engineers conducting field surveys. After the war, he eventually became the Surveyor-General of British Columbia. Later in life he reflected on his time as a Soldier of the Soil and stated “my experiences at Purves…surely contributed to any success in later life.”

Mary E. Plummer

Canadian Field Comforts Commission

Biography

Mary Elizabeth Plummer was an early supporter of the war effort. Only a few weeks after the war began, Elizabeth and the other committee members of the Canadian Women’s Hospital Ship Fund raised over $100,000 to finance a hospital ship. That October, she sailed to England with the First Canadian Contingent to run the newly formed Canadian Field Comforts Commission. Working out of Moore Barracks in Shorncliffe, Elizabeth organized the creation and distribution of care packages to members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. In 1916, She became an Honorary Captain and continued serving with the commission until 1919.

Opposing the War

Obviously, support for the war was not unanimous in Canada. In Quebec, in particular, a large segment of the population strongly opposed taking part in a conflict that seemed far removed from their interests. Opposition to the war was not limited to Quebec, however. In fact, many spheres of Canadian society, both French-speaking and English-speaking, opposed the war and, more specifically, the potential use of conscription as a means of recruitment. This was especially true for union workers, farmers and suffragettes.

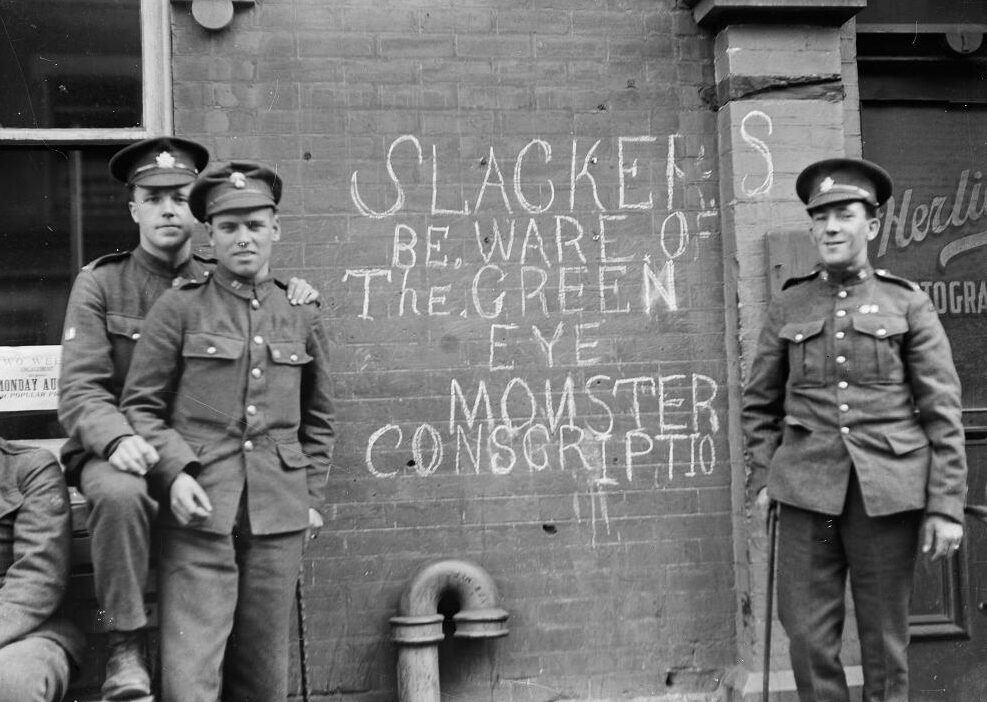

Outright opposition to the war was not, however, a common or popular position. Indeed, even the greatest critics of conscription were, for the most part, in favor of military participation in Europe. Many Canadians even vehemently supported the war. In Toronto in 1917, wounded veterans who regularly congregated at an area called “Shrapnel Corners” near a local military hospital began writing pro-conscription graffiti: “DOWN WITH THE SLACKER” – “slacker” being a negative term for young people who hadn’t enlisted for war.

Despite popular sentiment, the recruitment rate dropped as news of the terrible battles in Europe reached the population. Many young people saw working at home to support the war effort as preferable to risking their lives in Europe.

The Conscription Crisis

Faced with a pressing need for new recruits, Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden broke an important promise that he had made to Canadians and authorized conscription with the passing of the Military Service Act on August 29, 1917. Many protested the decision, especially in Quebec, where support for the war was lower than elsewhere in Canada. To shore up support, Borden called a new election in 1917 on the theme of conscription. Although he won the election easily, defeating his rival and the leader of the anti-conscription movement, Wilfrid Laurier, it became one of the most controversial elections in Canadian history.

Conscientious Objectors

When conscription became compulsory, hundreds of young people openly protested and refused to become soldiers – they are what we call “conscientious objectors”. For these people, the reasons for opposing conscription were diverse. For example, some were motivated by religious convictions. In Ontario and Western Canada, Mennonite, Quaker and Seventh-Day Adventist communities asked the federal government for exemptions from service for their members. Others opposed the war for political reasons: out of pacifist conviction, or in opposition to what they perceived to be an imperialist war.

With a new government and strong support across English-speaking Canada, Borden was able to move forward with conscription. However, the issue was not entirely settled, and tensions were higher than ever in Quebec. On March 28, 1917, in Quebec City, police arrested Joseph Mercier for failing to report to the recruiting office. A crowd of 2 000 gathered at the site of his arrest and demanded the young man’s release. Although the police released Mercier soon thereafter, tensions in the city remained high.

Over the next few days, citizens organized several rallies to protest against conscription. The demonstrators, as well as some vandals, particularly targeted pro-conscription newspapers, police stations and military buildings. Fearing a province-wide outbreak, the authorities sent in the army. Faced with a hostile crowd, the army opened fire on April 1, 1917 causing four deaths and over thirty injuries. The government declared martial law a few days later, putting an end to the demonstrations.