REALITIES OF WAR

The War Begins

The war on the Western Front was fought in trenches – long, narrow, deep, and muddy ditches. The trenches were extraordinarily uncomfortable and soldiers in the trenches were under frequent enemy artillery fire. The soldiers lived with vermin such as rats, lice, maggots, and flies which created serious health risks. The trenches were also constantly exposed to the weather. Canadian Infantry soldiers were rotated in and out of the trenches, as it was the most dangerous place on earth to be.

Explore: Examine these images of Canadians in the war. What were the conditions like? What type of training, or equipment might you need to prepare for life on the front?

“[…] there was a line up of trenches, you know, 1, 2, 3, 4 as you went and you got, you gradually moved into the line with the mud. Things weren’t too good, we had to squat lots of times and dig a trench under the ground just enough, a foot deep, you know, so you could lay there. The shell fire, the Germans weren’t that far away and it was clay, I remember you hit clay. You were working fast, bullets were flying around, you were working fast to get some shelter, see, and that clay, my God, we cursed it.”

— Harry Routhier (source)

In August 1914, at the beginning of the war, Canada’s army had barely 3 000 regular troops. That fall, just over 30 000 volunteers trained for deployment in Britain, and then deployed to the front lines in France. This first contingent of 32 000 soldiers made up the 1st Division of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). Additional men were recruited thereafter and became part of the second, third, and fourth divisions of the CEF.

In addition to the soldiers and nurses recruited, the Canadian Army also deployed thousands of animals to the front line. For example, horses were used for logistical support to bring supplies to the front because they were more reliable than vehicles, especially in the mud. In fact, approximately 256 000 horses and mules perished alongside the Commonwealth armies on the Western Front.

A New Age of Warfare

WWI was a new type of war, transformed by new technology, specifically new types of weapons. Bolt action rifles replaced the standard musket as the primary weapon for infantry forces in all armies. In the first few years of the war, the Canadian Army used the Ross rifle, which often jammed when exposed to dirt and dust, rendering it useless in trench warfare. Demonstrating a capacity to adapt to the unexpected, the Canadians replaced the Ross rifle with the British Lee-Enfield, which was more suitable for the harsh conditions in the trenches.

“We had the old Ross rifle. Well it was clumsy. It would shoot alright but you pull the bolt straight back and at a certain point as you pull it back, the head of the bolt twisted about 90 degrees and when you pulled the bolt, went straight back and straight forward, it was a clumsy rifle but the Lee Enfield was a nice rifle.”

— John Babcock (source)

The switch from muskets to rifles meant that armies had to change their tactics on the frontlines. In other words, soldiers no longer stood still in lines shooting at each other! Instead, they used cover and moved in small groups. These tactical changes also led to uniform changes. Known for wearing bright red uniforms in past conflicts, soldiers of the British Empire switched to a standard khaki uniform. Indeed, wearing a drab color was a good way to camouflage on the battlefield.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force soldiers wore the same uniform, which was made from thick wool and dyed in khaki. Each soldier carried around 60 pounds of equipment, transporting such necessities as munitions, a flashlight, a sewing kit, a compass and, most importantly, a gas mask. The officers were also allowed to carry certain objects with them such as a whistle, a camera and a handgun. Adding to that, the weight of mud collected on uniforms and equipment typically added another 60 pounds, which made their lives more difficult!

A First World War replica uniform held by the Queen’s Own Rifles Museum. This uniform was designed to adapt to the new type of war delivered in Europe. Notice the webbing which served to hold ammunitions, canteen, tools and personal objects.

As the war dragged on, combatting nations developed new weapons in an effort to gain the upper hand. Examples include artillery cannons, bombs and poison gas, which famously caused a great number of casualties among the soldiers deployed. WWI also saw the creation of a new type of vehicle: the tank. Known at the time as “land battleships”, tanks were mechanically unsound and often broke down. They were also rudimentary and slow, but given that they were approximately the size of a modern school bus, they still created panic amongst the German soldiers.

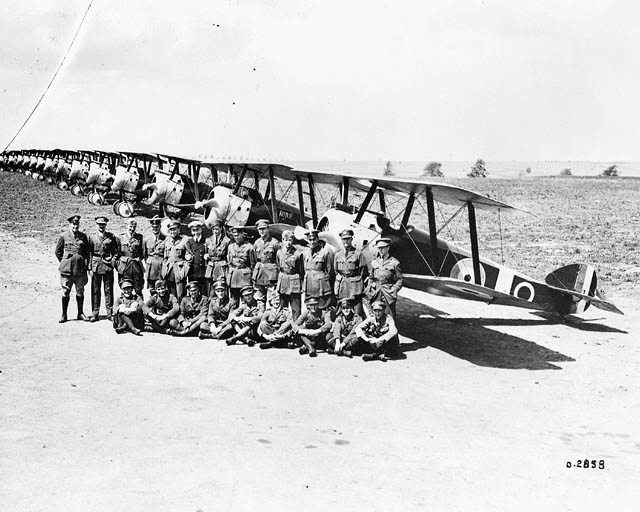

The use of submarines was another innovation for the Canadian Navy. In 1914, the Navy acquired two submarines to protect their coast. While they were never used in combat, these two ships were the first of this type to be used by Canada.

The MacAdam Shield Shovel

Canadian Minister Sam Hughes inspect a MacAdam Shield Shovel at Valcartier Camp, in Quebec, in September 19, 1914 (Imperial War Museums).

Not all inventions were successful, and some were even quite goofy. In 1914, Canadian minister for the Department of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes, introduced the MacAdam Shield Shovel. Based on an idea from his secretary, Ena MacAdam, the MacAdam Shield Shovel was intended to serve as both a shield… and a shovel. Featuring a large hole in the middle for the barrel of a rifle, the metal sheet was intended to protect a soldier from enemy gunfire while taking aim. It was also intended for use in digging trenches and holes. The Canadian Government quickly ordered 25,000 shield shovels. Unfortunately, they soon realized that the invention was nearly useless: the metal was not thick enough to serve as a shield and the gaping hole in the middle made it pointless as a shovel. Embarrassed, the Canadian Army quietly discontinued the Shield Shovel and moved on.

What is a soldier?

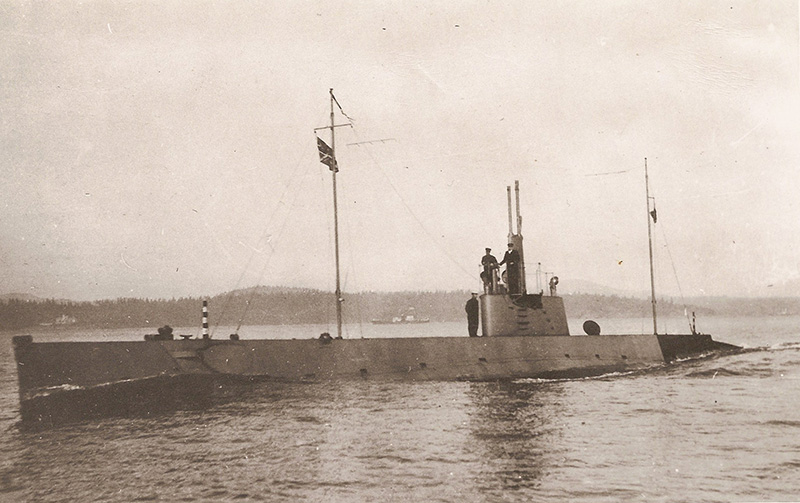

At the beginning of the war, thousands of young men joined the military. At the time, the military was composed of three branches: the army, the air force, and the navy. All of these branches had both combat and non-combat roles.

Combat roles imply that the recruit directly engages enemy forces whether in the sea, in the air or in the trenches. Equally important but less often recognized, many other people took on various non-combat support roles working as administrators, cooks, or drivers. Many of these individuals were deployed near the frontlines and their roles were not without danger.

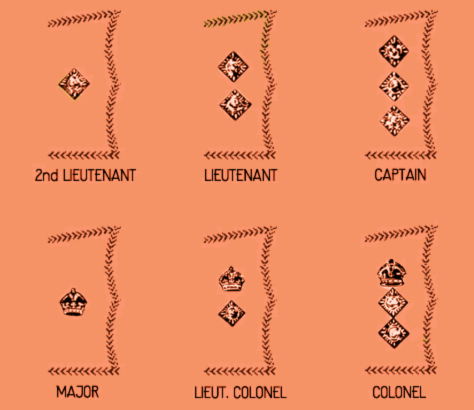

All branches of the military, combat and non-combat, follow a similar hierarchy and are led by officers. An officer has a wide range of responsibilities, such as coming up with plans and overseeing operations and daily activities.

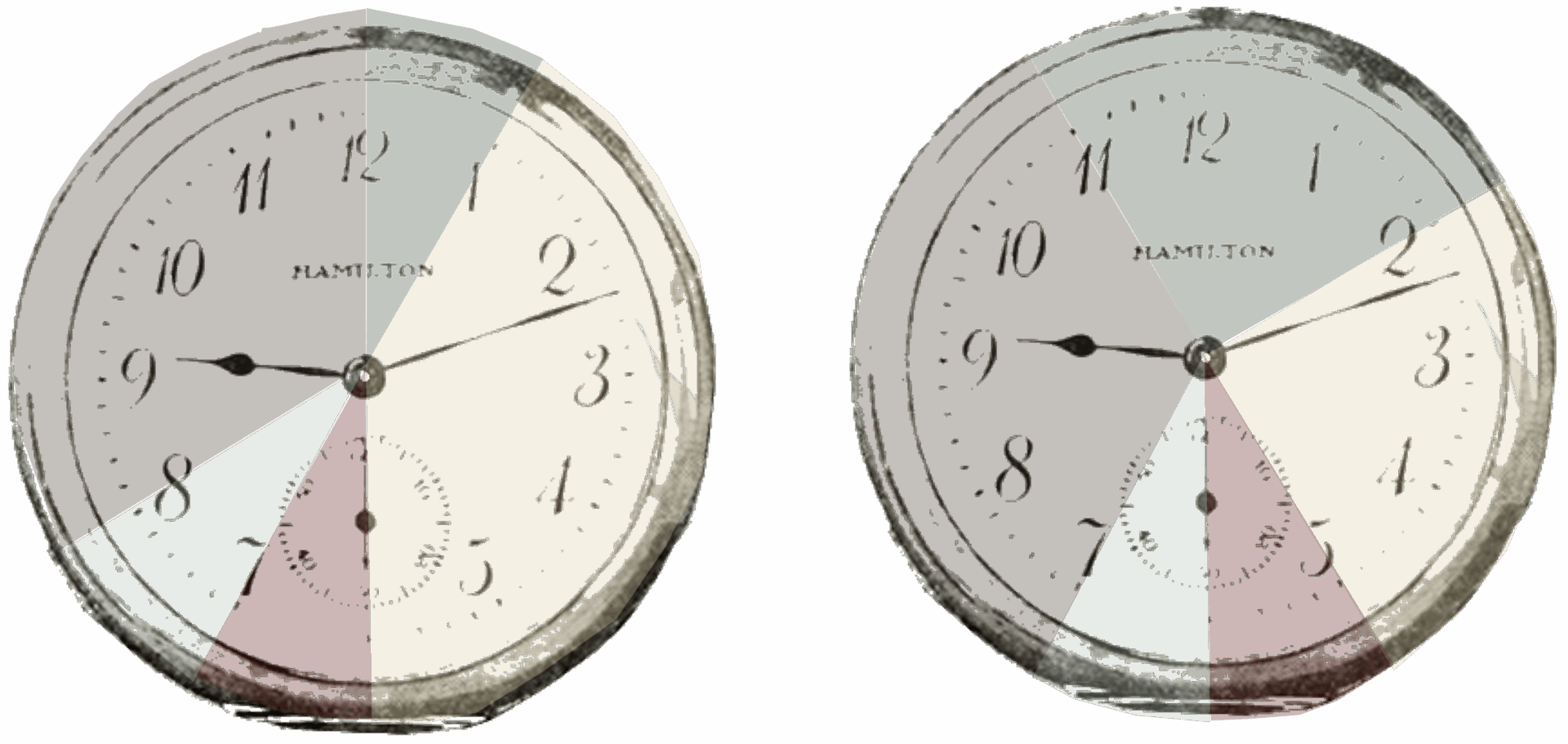

Discover: Click on the clocks to see what a typical combat soldier’s day looked like. Did you find anything surprising?

A typical Officer’s Kit

Aside from responsibilities, the biggest difference between a soldier and an officer was their pay! In August 1914, the daily pay rate for a Private was $1.00 a day – according to the Bank of Canada inflation calculator, which is approximately $27.40 in 2025! In comparison, a Corporal would get a raise of ten cents (equivalent to $2.74 more today) and a Colonel, the highest-ranking senior officer (but below General ranks), would earn $6.00 (equivalent to $164.40 today) as their daily pay rate.

Think: Would you fight for a dollar? Do you think this was enough money for soldiers at the time?

The Nursing Sisters

Thousands of Canadian women enrolled as military nurses at the start of the First World War. These women were usually deployed in Europe, whether in field hospitals or hospital ships, and cared for the many injured soldiers. The average daily rate for a Nursing Sister attached to the CEF was double that of a Private, earning $2.00 a day, equivalent to $54.80 today. This was quite a lot by the standards of the time, but quite low for today’s!

To learn more about the role of Canadian military nurses, visit our exhibition They Cared: the Origins of Military Nursing!