WAR BREAKS OUT

What Caused the First World War?

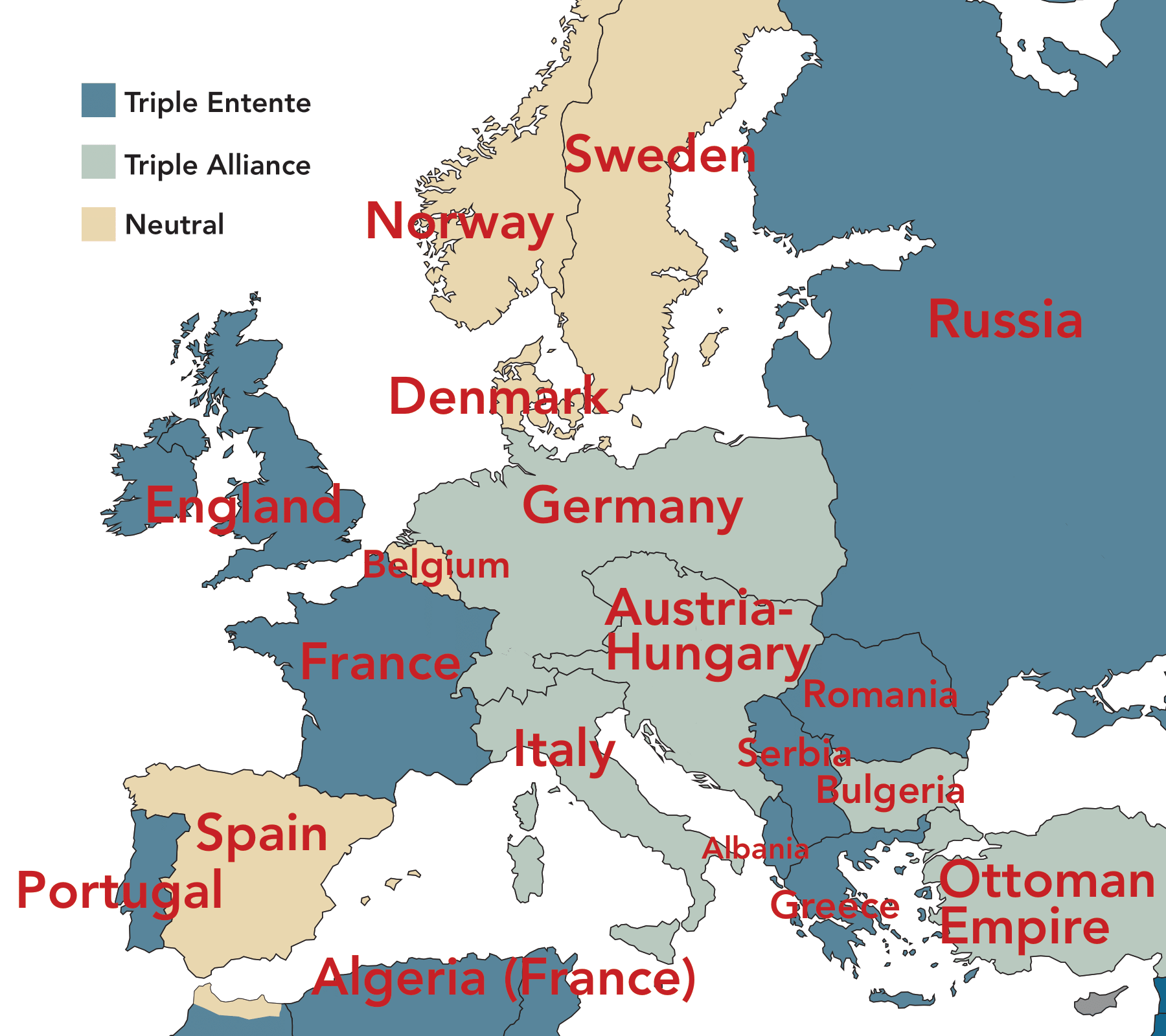

Discover: Explore the map to see what Europe looked like in 1914.

Map Data: Kropelnicki, Jeffrey; Johnson, Grace; Kne, Len; Lindberg, Mark. (2022). Historical National Boundaries. Retrieved from the Data Repository for the University of Minnesota, https://doi.org/10.13020/146x-1412.

A map of Europe in 1914 would look very different from a map of Europe today. Eastern Europe, especially, was divided amongst a series of empires: the German empire, the Austro-Hungarian empire and the Ottoman empire. These empires, along with Western European countries, were in constant competition with one another. Indeed, decades of imperial rivalries, economic competition, nationalism, and instability all led to a very fragile and unstable peace in Europe at the turn of the 20th century.

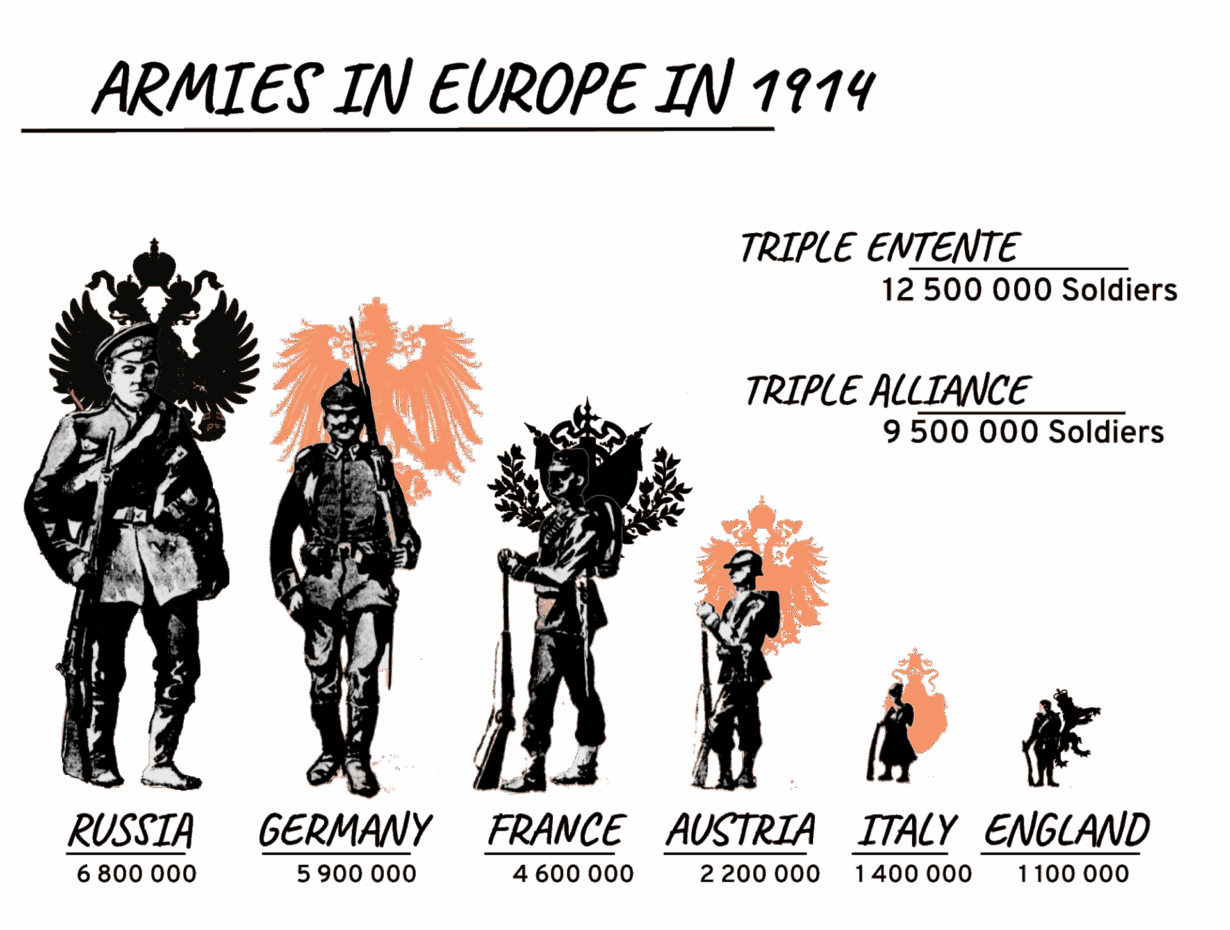

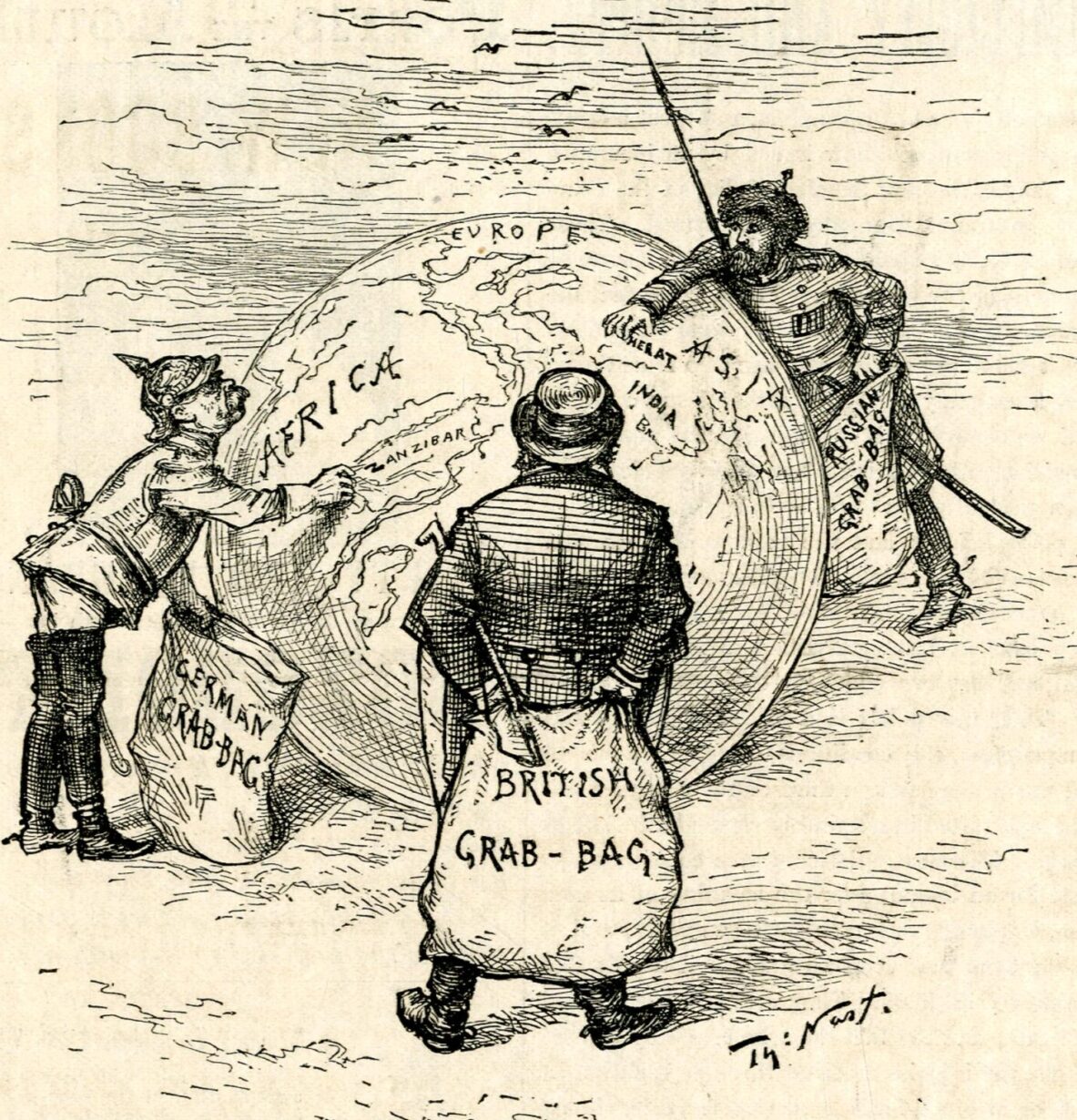

We can refer to the following as the MAIN causes of WWI: Militarism, Alliances, Imperialism and Nationalism.

MAIN Causes of the First World War

How did Canada get involved?

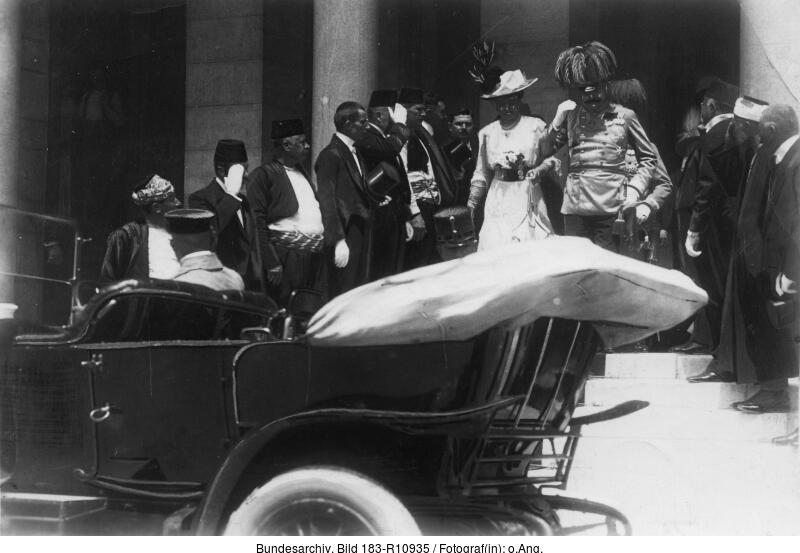

When the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on Serbia, many countries were bound by treaties and thus obligated to join the conflict. Russia, allied to Serbia, declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Germany, allied with the Austro-Hungarians, then stepped in and demanded a promise of peace from Russia and its ally, France. When the Germans received no reply, they declared war on Russia on August 1, 1914, and on France on August 3, 1914.

On its way to France, the German army invaded Belgium on August 3rd, 1914. Britain, an ally of France and supporter of Belgian neutrality, demanded that the Germans withdraw from Belgium and that Germany observe the Treaty of 1839 which declared Belgium a neutral country. Despite the ultimatum from the British, the Germans continued their invasion and Britain declared war on Germany on August 4th.

Many European countries were major colonial powers at the time. Their involvement in the conflict therefore meant that their colonies were automatically at war as well. As a result, the First World War involved people from all over the world. Although the fighting mainly took place in Europe, Africa and the Middle-East also saw their own theatres of war.

Canada was a self-governing Dominion of the British Empire, but did not fully determine or control its own foreign affairs. Therefore, Canada was obliged to enter the War alongside Britain, which asked Canada to deploy 25,000 soldiers. The Canadian Government thought that the might of the British Empire would make for a short-fought war with Germany. Little did they know it would last four long years and enlist 619 636 Canadians, almost 13% of Canada’s population of 8 million.

Enlistment

When war broke out, Canadians rushed to enlist in large numbers. Many chose to enlist out of feelings of patriotism and the desire to fight a just war against German aggression. Some also wished to enlist for adventure and travel. Newspapers, posters, clergymen and politicians encouraged men to enlist as a duty to King and Country.

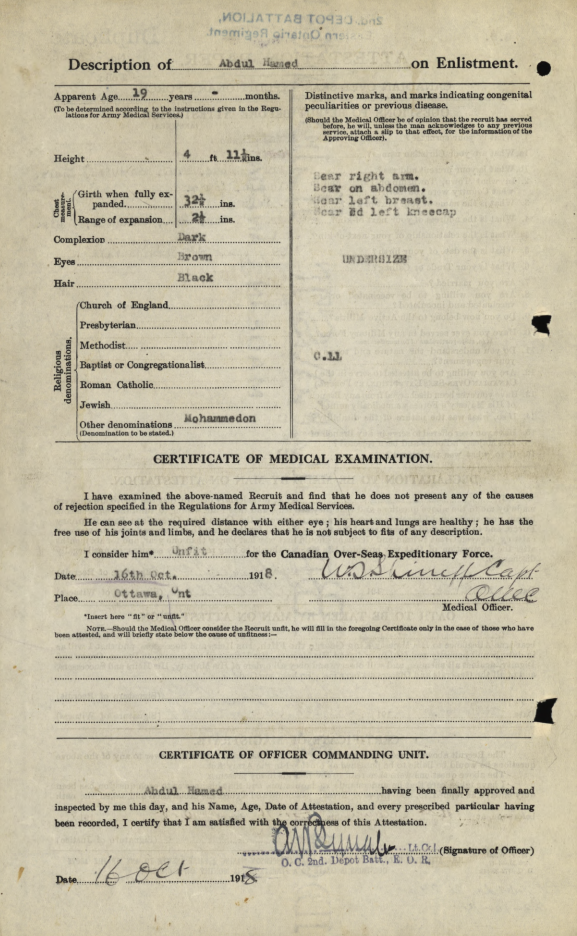

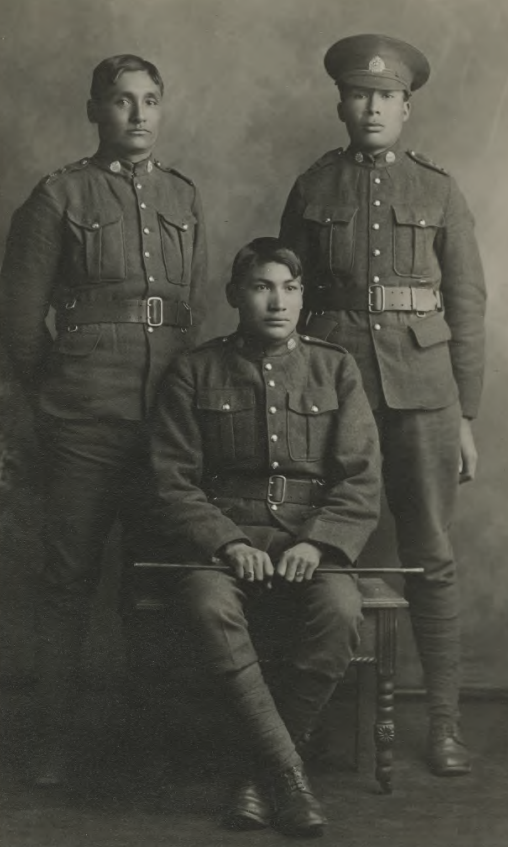

Early in the war, volunteers overwhelmed Canadian recruiting offices. Recruiters followed government-mandated medical requirements and turned away numerous men whom they deemed “unfit” or “undesirable” whether due to their age, height, medical history or even the colour of their skin. While there was no government policy on the ethnicity of volunteers, many recruiters ascribed to the belief that this was a “white man’s war” and turned away Asian, Indigenous and Black Canadians. This decision was, however, frequently left to the discretion of the recruiting officer and some recruiting officers accepted all eligible fighters, including Indigenous, Black and Asian Canadians, amongst their ranks. As the war progressed and the troops overseas faced heavy losses, Canada needed more soldiers and loosened its restrictions on recruitment.

Did you know?

The youngest recorded age of a Canadian soldier that enlisted in the CEF was 11. The oldest was 78. In both cases, they lied about their age.

Discover: For some, enlistment was a simple process. Others went to great lengths to enlist, showing a powerful determination to fight for what they felt was right. Explore the stories below to learn more

Regimental Case Studies

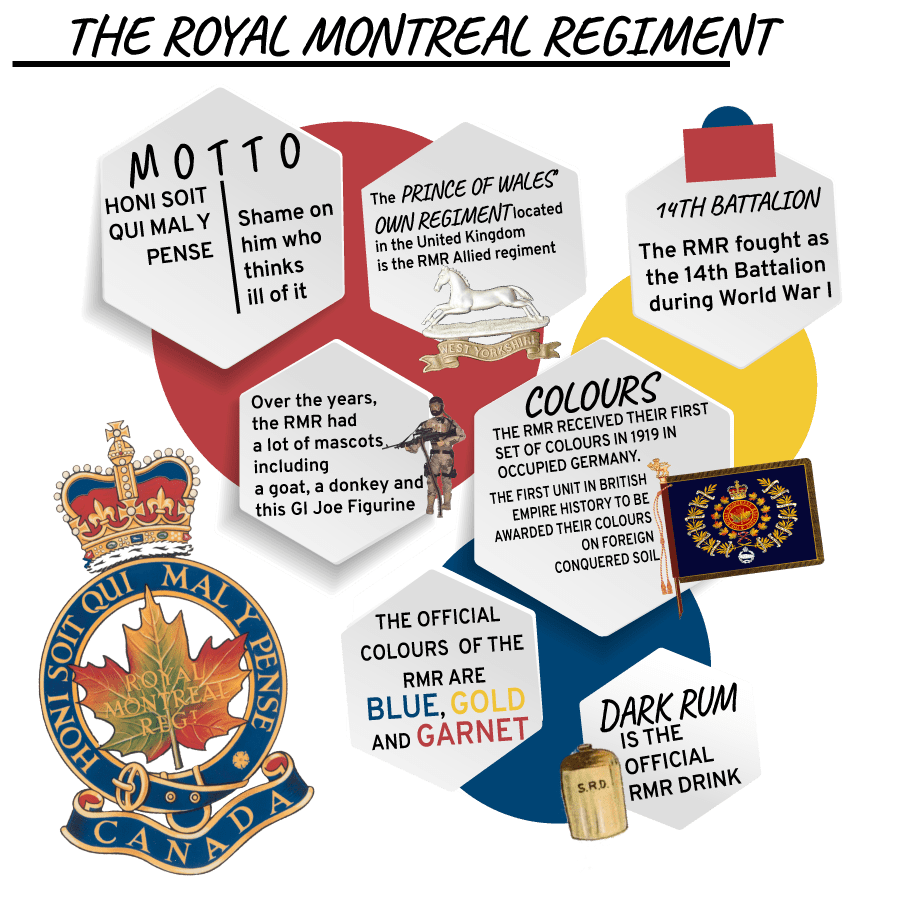

When war broke out, many Montrealers wanted to do their part to fight the enemy and answered the call to arms with enthusiasm. To coordinate the city’s war effort, the Royal Montreal Regiment was created in early August 1914. At that time it was called the “1st Regiment, Royal Montreal Regiment” and it was formed by combining three existing prominent militia regiments in Montreal: The 1st Regiment, Canadian Grenadier Guards (372 men and 12 officers); The 3rd Regiment, Victoria Rifles of Canada (355 men and 12 officers), and the 65th Regiment, Carabiniers Mont-Royal (276 men and 8 officers).

Shortly thereafter, the Minister of Militia created the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) so that all of the 424 000 Canadians that went to France and Belgium between 1914 and 1918 were part of the same centrally organized force. Within this military organization, The Royal Montreal Regiment was known as the 14th Battalion (RMR) CEF.

Composed of both English and French speaking men, the RMR “illustrated more than any other battalion in the 1st Canadian Division the spirit of unity between those two great races.”

French Canadians had been in North America for several generations and did not feel any particular loyalty or proximity to Europe, the land of their distant ancestors. On the contrary, many English-speaking Canadians were the first or second generation of their family in the country and felt affected personally by the conflict. Nevertheless, it was clear to both groups that the conflict was global in nature. Criticisms regarding the low level of participation of Francophones in the war effort were upsetting. Wanting to prove their patriotism, a Francophone delegation was formed and they officially requested the creation of a French-Canadian battalion in front of the Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden on September 28, 1914, in Ottawa.

Arthur Mignault, a doctor who had made his fortune in the pharmaceutical industry and who was Major Surgeon of the Mont-Royal Carabinieri Militia, ancestor of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal de Montréal, offered $50,000 of his personal fortune to create and equip a French-speaking Battalion. He wanted a Battalion that could bring together French Canadians across the country and even Franco-Americans residing in the United States. In 1914, $50,000 was a colossal sum!

These initiatives were publicized by the newspaper La Presse, whose managing editor, Lorenzo Prince, supported the cause. La Presse called for the formation of a French-speaking unit from the beginning of the war and the paper remained a valuable recruitment tool. A crowd of about 20 000 people gathered to hear the speeches of the French-Canadian delegation in favour of the creation of a French-speaking military unit.

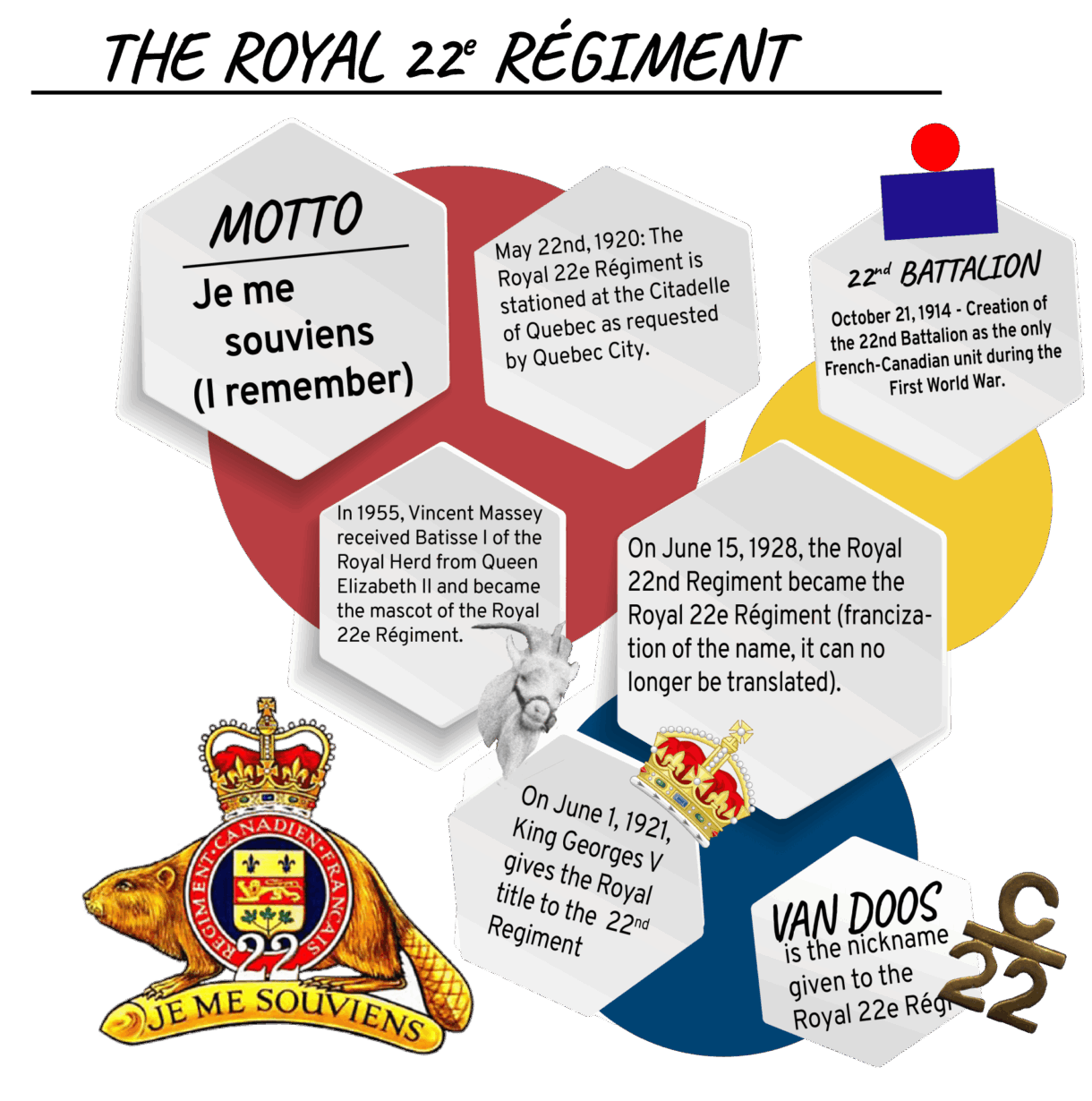

Faced with such a strong movement, Borden agreed to the creation of a French-speaking infantry battalion. On October 21, 1914, it was created as the Royal French Canadian Regiment. Since the battalions that were integrated into the Canadian Expeditionary Force were numbered, the Regiment was given the number 22. And thus the 22nd French-Canadian Battalion was born!