The ‘Spanish’ Influenza Pandemic of 1918

World War I may have ended on November 11, 1918, but the wave of death sweeping the world did not. In 1918 an influenza pandemic, known, however erroneously, as the Spanish flu, spread around the world killing an estimated 50 million people, with most deaths occurring in the lethal second wave of late 1918. In absolute numbers, the Spanish flu is the deadliest pandemic in history.

Caused by a virulent strain of the H1N1 flu virus and aided in its global spread by the movement of troops, the ‘Spanish’ flu was also distinctive because it disproportionately affected young, otherwise healthy individuals. The average age of death was 28, roughly the same average age of death as that of soldiers. Both at home and abroad, nurses were on the front lines of the 1918 influenza pandemic; some paid the ultimate price with their lives.

Letter from James William Stares to Mr. Irwin, July 21, 1918

“I have been feeling very tough lately. I have been in Hospital, suffering with the latest epidemic The “Spanish Flu” not a very nice thing to have.

Severe Headache, partial loss of legs, aches and pains all over, and feverish. For one week I just gazed at the ceiling, counting the flies, working out imaginary patterns on the paintwork, going through some of the Battles again, (in my mind) killing Germans by the thousands. The lad in the next bed thought it safer underneath the bed. (suppose I was delirious) I had to laugh when he told me about it. And say I had a peach of a nurse, she was a Dandy. I Love my Nurse.”

(www.canadianletters.ca)

Timeline

First wave (Spring 1918) – Second Wave (Fall 1918)

Photos: American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine, BAnQ, American Photo Archives, BAC-LAC

Symptoms

Some cases of influenza presented as a normal flu with high fever, aches and coughing. Influenza was often complicated by severe pneumonia. In more serious cases, some patients bled spontaneously from their noses, mouths and even eyes. Some coughed blood and some saw their skin change colour, first with mahogany spots appearing on their cheeks and then their faces and hands, slowly turning blue from lack of oxygen This was known as cyanosis and was a sign that death was near.

(Image : Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine)

Where did the ‘Spanish’ Flu come from?

Historians and epidemiologists still debate the subject, but there is no confirmed hypothesis. Doctors at the time could not sequence the virus – they couldn’t even see viruses with the microscopes of the era! Furthermore, there are no surviving tissue samples that modern scientists can consult to definitively decode the origins of the virus. Theories of the virus’ origins include: Étaples, France (similar cases in 1916), Shansi, China (similar case in 1917) and Haskell County, Kansas, USA (similar cases recorded not far military training camps in January 1918). What we do know is that influenza did not come from Spain. It came to be called the Spanish flu because Spain was neutral in WWI and did not censor its newspapers like most of the countries at war.

(Photo: Naval Historical Society)

Letter from Emily Adams to George Walter Adams, Oct 22, 1918

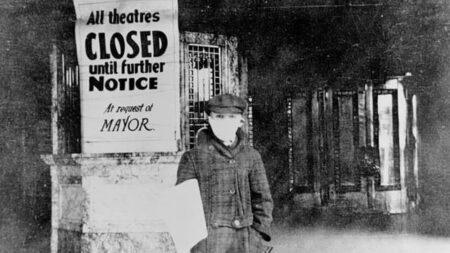

“I expect you have heard we have two epidemics – 1 Spanish Influenza, the other pneumonia. It has become so serious that theatres & picture shows are closed and churches are only allowed to have one service. The Arlington Hotel is turned into an hospital also Mossop House. You will be sorry to hear Frank Bresetor died of pneumonia last week … Fred Hall went to fetch the body & told Charlie there were 60 bodies on the train.”

‘Spanish’ Influenza in Canada

It is estimated that around 55,000 people died of influenza and influenza-related illnesses in Canada. These deaths were concentrated, for the most part, over a few short weeks in the fall of 1918. Many think that the second wave of influenza came to Canada with injured soldiers returning home from war. In fact, after the Llandovery Castle disaster, Canada no longer transported injured soldiers back to Canada on hospital ships. Indeed, the second wave came to Canada via the United States, with sick soldiers stopping in Canadian port cities such as Halifax and Montreal. Thousands of soldiers were still leaving the United States and Canada to help win the war in Europe!

In 1918, Canada also mobilized the Siberian Expeditionary Force, a force of about 4000 men who were sent to Russia to prevent Germany from gaining access to Russian oilfields. These men were drawn from bases all over Canada and shipped westward with great secrecy. They, of course, brought influenza with them wherever they stopped. City officials, unaware of the top-secret mobilization, were unprepared for the outbreaks that ensued.

With outbreaks of illness all over Canada happening almost simultaneously, there was an increased need for nurses and doctors. The nation, however, had a shortage of nurses because so many were serving overseas. Hundreds of women with and without medical training therefore volunteered to serve on the home front as Volunteer Aid Detachment nurses, risking their lives to care for the ill and dying. These nurses helped by giving patients baths and medication, making sure they were hydrated and monitoring their vital signs, among other things.

‘Cures’ for Influenza

There was no cure for influenza and antibiotics, which would have been able to treat the pneumonia that often accompanied it, had not been discovered yet. The most effective treatment and the best predictor for a positive patient outcome was support and care from a skilled nursing staff.

That does not mean that scientists, doctors and others did not try to find a cure. In fact, “cures” for influenza abounded, though they were at best ineffective and at worst, dangerous. There was very little regulation over the pharmaceutical industry in 1918 and numerous companies tried to turn the pandemic into a money-making opportunity, quickly marketing ‘preventive treatments’ and ‘cures.’ Most were benign, but some caused serious side effects if taken in large quantities.

Doctors also prescribed dangerously high doses of aspirin, and experimented with mercury, arsenic and strychnine (all of which are poisonous).

Preventive Measures

Around the world, doctors and public health officials relied on non-pharmaceutical interventions to prevent the spread of illness. Frequent non-pharmaceutical measures included closing schools, theatres and places of worship, quarantining ports, setting up isolation wards and advising the public to avoid crowds, to keep their windows open and to wash their hands. Some places also recommended wearing a gauze mask.

In Canada, with no centralized board of public health, measures and recommendations varied from province to province and city to city. Indeed, some municipalities defied the recommendations set out by provincial authorities! In British Columbia, for example, the province recommended closing schools, but the city of Vancouver refused, significantly delaying closures. Alberta was the only province that required citizens to wear a mask, but it had very little means to enforce the new law and few complied.

(Photo: Alberta Board of Health – University of Calgary Press)

In Quebec, Montreal was very hard hit by the second wave. Influenza appeared in military barracks on September 20th and showed up in city schools within a week. The death toll peaked at over 200 deaths per day (in the city of Montreal alone) a month later, on October 21st. The city didn’t act until October 7th, when officials closed schools, theatres and public institutions. Defying resistance from religious leaders, the city closed places of worship several days later.

(Photo: La Presse, 12 octobre 1918, BAnQ)