The Realities of Nursing

Women in the 19th century were not seen as equal to men and were limited to performing very specific roles. Until 1891, women were not even allowed proper education; they were groomed to become mothers, caretakers and housewives. When the Great War broke out, women saw their roles change. They became factory workers, munitions experts and nurses. The right to vote was seen as the main barrier to equal rights for women and, even though the suffragette movement predates the war, it was during the conflict that it gained the most support.

The Canadian Nurses who served in the military in WWI were trained nurses before the war and were volunteers. Most were between the ages of 21 and 38. Though the practice of nursing did not change in any appreciable way during WWI, the importance of the nurses’ role as an essential component in medical care within the theatre of war was consolidated. Nurses were able to provide specialized health care skills that were vital to the health and recovery of the soldiers, even where medical measures were limited and diseases flourished. Nurses perceived themselves as soldiers, as patriots. They became part of the army, no longer passive but active, and their expertise aided the allied victory. Contemporary writings about nurses saw them as heroines and as symbols of courage.

The nursing profession had just begun to take shape when the Great War broke out. Since this occupation was so new, people were not quite sure what to expect of a nurse. Everyone formed their opinion on what their duties were and how they were supposed to behave. As a consequence, several identity tropes started to emerge of what a “typical” nurse was like.

The Pillars of Nursing

Care

Nurses tended to horrific wounds and comforted dying soldiers. They would apply bandages, monitor vital signs (heartbeat, blood pressure, breathing), and take urine and stool samples. The valuable data collected provided a strategic vision of the general health of the soldiers and helped the army in decisions regarding the war effort.

French wounded in Montreal Ward, No. 8 General Hospital, St. Cloud, Paris. September, 1917 (BAC-LAC)

Construction

Nurses often had to build their own medical compounds. In doing so their tremendous work ethic was apparent, often treating patients in sub-par conditions before the hospital was officially ready to receive patients.

Canadian nursing sisters rebuilding after a German air raid, June 1918 (BAC-LAC)

Comfort

Nurses went out of their way, in both the field hospitals and stationary hospitals, to organize outings and holiday celebrations – such as Christmas, Easter or Halloween – in order to keep the wounded soldiers’ morale up.

(Nurses and soldiers dancing at a social event, Australian War Memorial)

Cleaning

When not tending to sick and wounded soldiers or constructing medical tents, nurses were busy mopping and cleaning. They ensured the cleanliness of the operating and care areas, and they sterilized the medical equipment. Essentially, it was the nurses who kept the wartime medical treatment of soldiers running effectively and efficiently.

(Australian War Memorial)

Daily Routine

The daily tasks of the Canadian nurses were incredibly varied. They were actively involved in all stages of the treatment of wounded soldiers. They were often involved in the construction of medical facilities while treating patients. They were also responsible for the physical rehabilitation of the wounded. Because of the large number of wounded soldiers, nurses cared for a large number of patients and saved many lives. Here is what a typical day in the life of a nursing sister looked like.

Afternoon

Evening

Morning

A look at the nurses’ uniform

Canadian Nursing Sisters were easily recognizable by their blue uniform and white veil, which earned them the nickname “bluebirds.” The uniform consisted of a blue double-breasted tunic, a long blue skirt made of sturdy fabric, white cuffs and a collar. Nurses frequently wore a white apron over their uniform. Some replaced the white veil with a large hat or helmet.

As officers, nurses also had formal wear, which was a darker blue with red trim accompanied by a cape for colder weather. Formal dress was only worn on special occasions and not on duty. Like other Canadian officers, nurses received an allowance to help cover the cost of their uniforms.

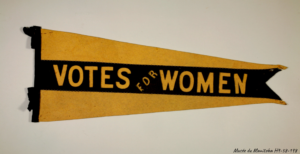

Women’s Vote

Women in Canada were given the right to vote gradually. At first, The Military Voters Act (1917) gave the right to vote to nurses and women in the armed forces. Later that same year, The Wartime Elections Act granted the right to vote to women who had a husband or a son fighting overseas. Both of these laws were part of Prime Minister Robert Borden’s strategy to increase support for conscription. He assumed that these targeted women would be more prone to support mandatory involvement in the CEF. After numerous denunciations from suffragettes, the Unionist government extended the right to vote to a majority of women in 1918 with the exception of Indigenous women, Asian women, and women from communities considered to be “enemy aliens.” Women in Quebec also could not vote in provincial elections until 1940.

Nursing sisters voting, 1917

Nursing Sisters at a Canadian hospital voting in the Canadian federal election, France, December 1917. (William Rider-Rider. Canada. Ministry of National Defence. Library and Archives Canada, PA-002279)

Training and Preparation

Canadian nurses during WWI went overseas to join the war effort with very little training apart from their nursing degree. They had to adapt their medical knowledge to vastly different scenarios to care for the wounded while working with their colleagues and learning how the military functioned. After the war, some of the nurses who returned home began making preparations, should another conflict occur. This included getting better equipment and supplies, and having better education and training . Nurses were integrated into the navy, army and air forces so that when Canada again found itself thrust into world conflict in 1939, there was no shortage of Nursing Sisters who were ready and prepared for action.

Overview

A total of 3,141 Nursing Sisters served in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps. 2,504 of those served overseas in England, France and the Eastern Mediterranean at Gallipoli, Alexandria and Salonika. By the end of the First World War, approximately 58 Nursing Sisters had given their lives, dying from enemy attacks (including the bombing of a hospital and the sinking of a hospital ship) or from disease.