At the beginning of the 20th century, China experienced numerous periods of insurrection that led to the advent of the Republic on January 1, 1912. Through the international actions of three major players – Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen – Canada’s Chinese communities saw themselves taking an active part in this revolution, though it was taking place on the other side of the Pacific.

On January 1, 1912, Sun Yat-sen proclaimed China a Republic, putting an end to 2,000 years of imperial history. The advent of this new regime was made possible by the success of what history refers to as the “Chinese Revolution”, which took place from October to December 1911. Although this movement was successful, it was only one of many episodes of insurrection that China experienced throughout the early 20th century.

After several defeats in the Opium Wars of 1842 and 1860, followed by the Sino-Japanese War in 1895, the Chinese imperial model no longer seemed adapted to the new realities of the world. Moreover, the reigning Qing dynasty was not Chinese, but Manchu. The emperors who ruled China were therefore foreigners, and the Chinese lived under occupation. It was against this backdrop of decline and political crisis, and of attempts to find solutions to the country’s problems, that protest movements emerged. While some of these movements were moderate and supported reform projects, others were radical and revolutionary, constantly trying to overthrow imperial power, thus making the turn of the twentieth century in China a particularly troubled and unstable period.

Many of the radical popular uprisings expressed a desire for change, inspired by the writings of a number of Chinese intellectuals of the time. Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen were among the most influential of these thinkers, reflecting on new political models and alternative forms of society. In addition to nurturing the revolutionary aspirations of the population, they were also agents of change, notably through their work with the Chinese diaspora. Whether promoting their reform projects abroad or organizing fund-raisers in overseas Chinese communities, Kang, Liang and Sun played a major role in the Chinese revolutionary process.

The Reformers: Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao

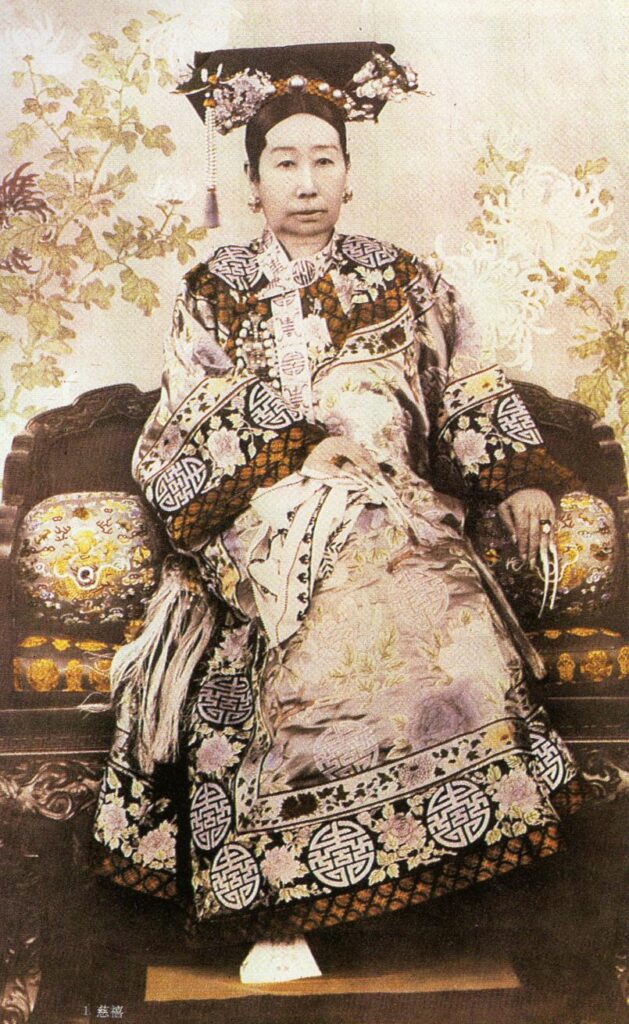

It was in this context that Kang Youwei first came to Canada in 1899. A few months earlier, he had to flee China after the failure of the “Hundred Days of Reform” movement, during which, supported by the young emperor Guanxu, Kang and other thinkers attempted a major modernization of the Chinese state. However, Empress Dowager Cixi staged a coup d’état and violently repressed the movement and its leaders (Kang Youwei’s brother, Kang Guangren, was one of the six leaders executed on September 28, 1898).

After a brief stay in Japan, Kang Youwei arrived in Canada as an exile in the summer of 1899. Undeterred by this failure, he founded the Chinese Empire Reform Association in Victoria on July 20, 1899, which would serve to relay his political program around the world, growing to 150 chapters by the early 20th century. Supported by British Columbia’s Chinese elite, the association soon opened chapters in Vancouver and New Westminster. After Victoria, Kang left for Montreal, where he stayed for a week before being received in Ottawa by Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier and Governor General Minto. He was also invited to attend a parliamentary session. Kang’s reform project was met with great enthusiasm, as it raised hopes of greater openness in China, and thus easier access to its markets. Kang Youwei returned to Canada in 1902, and again in 1904, for a third and final visit to Vancouver, where he had the opportunity to meet and talk with the American consul.

A disciple of Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao visited Canada in 1903. On this occasion, he embarked on a full-scale tour of the country, meeting with most of the country’s Chinese communities to raise funds in support of the revolutionary cause. In his memoirs, Liang testifies to the strong impression made on him by Quebec society. After spending a week in Montreal, he described it as the most dynamic city he had seen in North America, attributing this to the coexistence of the French and English-speaking worlds in the same space. Like Kang, he attended a session of Parliament in Ottawa and met Conservative Party leader and future Prime Minister Robert Borden. Following Liang’s visits to these cities, branches of the Chinese Empire Reform Association were established in Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa, while a final branch was founded seven years later, in 1910, in Calgary.

The Revolutionary: Sun Yat-sen

Like Kang Youwei, Sun Yat-sen visited Canada three times in 1897, 1910 and 1911. A wanted man after a failed coup d’état in 1895, Sun was in exile in England in 1897 when a bizarre kidnapping attempt took place in front of the Chinese embassy in London. At the time, he was just another revolutionary, but this episode, publicized by the British press, made him an international celebrity. Bolstered by his new status, Sun left Great Britain for Canada in July 1897. He stayed in Montreal for four days, during which time he founded a chapter of the Society for the Rehabilitation of China, his first organization, which he had founded in 1894 while living in Hawaii. He also collected funds to finance a crossing from Vancouver to Yokohama.

It was not until thirteen years later that Sun returned to Canada. Between these two trips, revolutionary ideas had spread throughout the country’s Chinese communities. Local organizations were formed to promote them, such as the Oath Society in British Columbia, and newspapers in Vancouver’s Chinatown relayed Sun’s ideas to members of the diaspora. Once again, Sun took advantage of his stay to raise funds for a new insurrection. Between 1895 and 1911, Sun Yat-sen led at least ten coup attempts to overthrow imperial Manchu rule.

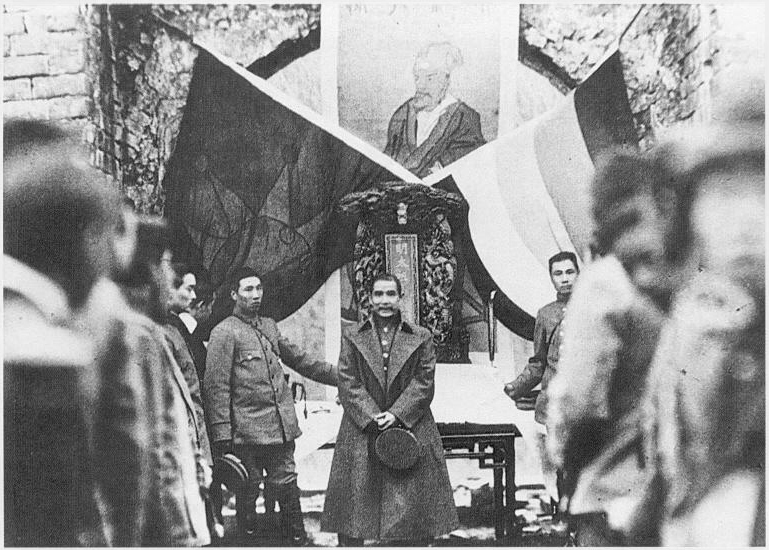

Sun returned to Canada for a third time in January 1911 for the purpose of raising money for his tenth and final insurrection plan. He managed to raise $35,000 from all of the Canadian chapters of the Chee Kung Tong, an association whose mission was to maintain order in the diaspora and help its members in need. The Chinese communities of Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Vancouver and Victoria all helped finance the Canton Uprising of March 1911. Unfortunately, the attempt failed once again. Sun Yat-sen was in Toronto when he learned, on March 29, that the uprising had been bloodily suppressed. In 1912, after the establishment of the Republic, a monument was erected in memory of the martyrs of the Canton Uprising. It featured the names of the Canadian cities that had contributed financially to this revolutionary episode.

The Canadian Legacy of the Chinese Revolution

Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen’s travels and fundraising activities in Canada illustrate how the country’s Chinese communities actively participated in the revolutionary process on the other side of the Pacific. If the inscription on the stele to the martyrs of Canton bears witness to this shared past, so too do the many Canadian branches of the Guomindang, the party founded by Sun Yat-sen when he became the first president of the new regime of the Republic of China on January 1, 1912. Until 2016, the facade of 617 rue Saint-Vallier in Quebec City bore a sign that read in Chinese: Chinese Nationalist Party of Canada. These were the offices of the local branch of the Guomindang, vestiges of a time when China’s political destiny was partly written in Canada.

Article written by Clément Broche, PhD candidate in history at the Université du Québec à Montréal, for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Marina Smyth.

Sources:

This article mobilized a number of first-hand sources for its writing. Here is a small list of some of the archive sources that were used:

- Liang Qichao, “Travel in the New World”, in Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook, New York, The Free Press, 1993, 524 p.

- Sun Yat-sen, Souvenirs d’un révolutionnaire chinois, Paris, Éditions Laville, 2016, 215 p. (in french).

For a more academic approach:

- Marie-Claire Bergère, Sun Yat-sen, Paris, Fayard, 1994, 563 p. (in french).

- Chang Hao, Liang Ch’i-ch’ao and Intellectual Transition in China, 1890-1907, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1971, 342 p.

- Harry Con, De la Chine au Canada : histoire des communautés chinoises au Canada, Ottawa, Secrétariat d’État du Canada, Division multiculturalisme, 1984, 375 p. (in french).

- Serge Granger, Le lys et le lotus : Les relations du Québec avec la Chine de 1650 à 1950, Montréal, VLB éditeur, 2005, 192 p. (in french).

- Yen Ching-hwang, « The overseas Chinese and the 1911 revolution », Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1976, 439 p.