KANDAHAR

At the end of 2005, the Canadian forces moved from the relative security of Kabul to Kandahar. By this time, ISAF had assumed control of security forces throughout Afghanistan and each participating NATO nation took on the security and reconstruction of a different Afghan province. Canada was assigned to Kandahar, home to the former Taliban capital and right over the border from Pakistan, where most of the remaining Taliban had fled. There they encountered a much different situation from Kabul: the local populace was suspicious and hostile, and the Taliban were determined to take back their stronghold. The Canadian forces had to adapt and the nature of the CIMIC and Psy Ops missions did as well.

CIMIC IN KANDAHAR

THE COUNTER-INSURGENCY

The Taliban, mostly Pashtun, had originally begun their movement in Kandahar and maintained strong ties with some of the Pashtun tribal groups there. Relations with the locals in the region were, therefore, more strained and hostile than they had been in Kabul.

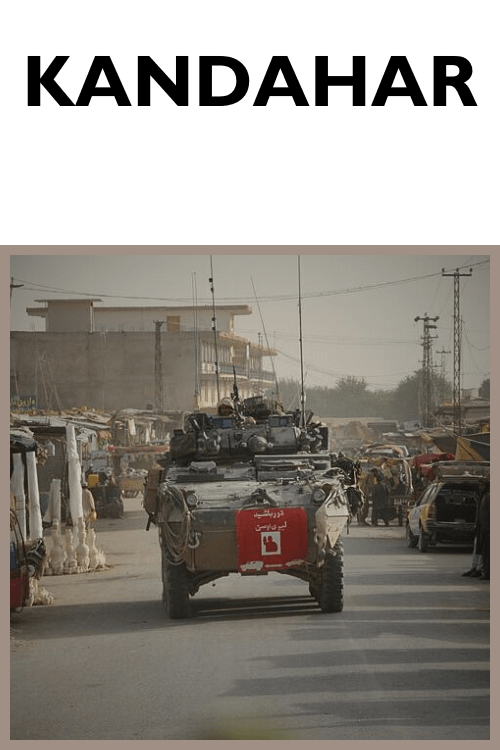

Around 2006, at the same time as the Canadians were arriving in Kandahar, the Taliban were regrouping and launching an attempt to take back Afghanistan. They infiltrated villages and developed strong points, a type of small defensive base, in and around Kandahar City. Despite the proximity of the Canadian bases, the Canadian soldiers out on patrol found themselves increasingly under attack. The Taliban fought mostly using guerrilla warfare tactics while hiding amongst the local population. Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), placed along routes taken by soldiers, and suicide bombers were responsible for the majority of Canadians killed.

Above: Patrolling the streets of Kandahar City was a regular part of life for the Canadian soldiers stationed there. However, patrolling was also a dangerous mission. In addition to having to operate in a dense urban environment, soldiers on patrol were also at risk of bombing or ambush from insurgents, for example.

Kandahar Provincial Reconstruction Team

When the Canadian forces moved south to Kandahar, the CIMIC teams became part of the Kandahar Provincial Reconstruction Team (KPRT), which was based out of Camp Nathan Smith.

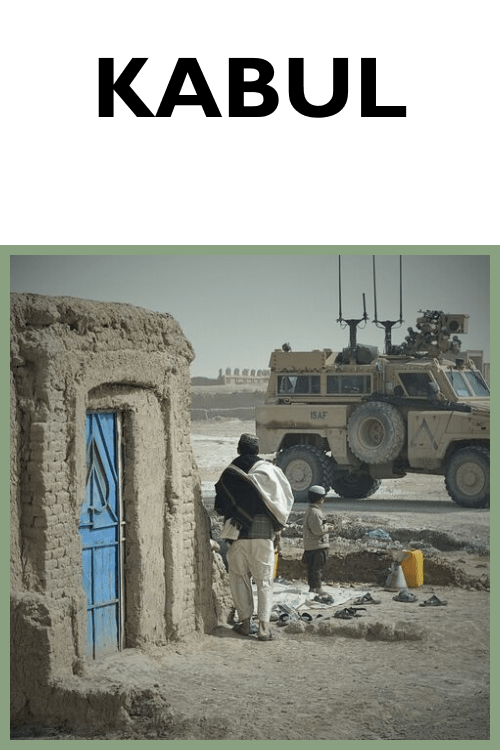

PRTs were joint civil and military operations intended to support development projects, improve security and empower local governments. Non-military personnel at a PRT often included diplomats, development workers, police and corrections officers. Military personnel consisted of military engineers, CIMIC teams who met and worked with locals and coordinated the resources of the PRT, and force protection, who would escort and protect both CIMIC teams and civilian aid workers.

Camp Nathan Smith

The Kandahar Provincial Reconstruction Team was based out of Camp Nathan Smith in a former fruit factory in the heart of Kandahar City. Named after a Canadian soldier killed by friendly fire in 2002, it was a medium-sized camp with Canadian cooks, a gym and even a pool. Despite being at the heart of the city, Camp Nathan Smith experienced less rocket fire and attacks than Kandahar Airfield, the neighbouring NATO coaliton base. This was likely due to the fact that the KPRT had worked on a number of development projects in neighbouring communities!

“CLEAR-HOLD-BUILD”

In this counterinsurgency context, influence activities such as CIMIC were of utmost importance due to the need to stabilize and win over the local population and to isolate the Taliban.

Canada employed a counterinsurgency strategy of “Clear – Hold – Build,” clearing out the Taliban, maintaining the security of the area and promoting its development. However, with limited troops and with a growing insurgency the Canadians would frequently clear an area and try to build basic services like schools, only for the Taliban to return months later and burn the school down.

PSYOPS IN KANDAHAR

PsyOps units played an important role in combat support in Kandahar. They sent messages on how civilians could protect themselves during an attack, where to go to be safe, and how to contact the army if they saw something suspicious. They could also target certain individuals suspected of being Taliban, and ask locals to report on these individuals. PsyOps units in the field could thus gather intelligence. They could also assess how effective types of messages were. These could then be tweaked by their counterparts at headquarters.

Messages to the enemy

The best way to protect soldiers from attack is to have an enemy who doesn’t attack at all. PSYOPS units worked to inform insurgents that if they surrendered, they would not be killed. The Taliban were not familiar with Western military conventions, such as the Geneva conventions, so PSYOPS units had to find ways to communicate that if they surrendered, they would have rights as prisoners. They also communicated how to properly surrender.

KAF, FOBs and Strongpoints

PsyOps headquarters were at Kandahar Air Field (KAF). KAF was a large, multinational camp based at the largest airport in the south of the country. It was ISAF’s regional headquarters in the south of the country and housed over 25,000 army personnel, civilian aid workers and support staff from Canada, the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands and numerous other countries.

PsyOps tactical units also spent a lot of time away from KAF in the field with combat brigades, staying in FOBs, or Forward Operating Bases, and Strongpoints. FOBs were small outposts, often in dangerous areas. They were well-secured, however, and many even had some creature comforts, such as cooks to prepare food, so that soldiers wouldn’t live off of hard rations.

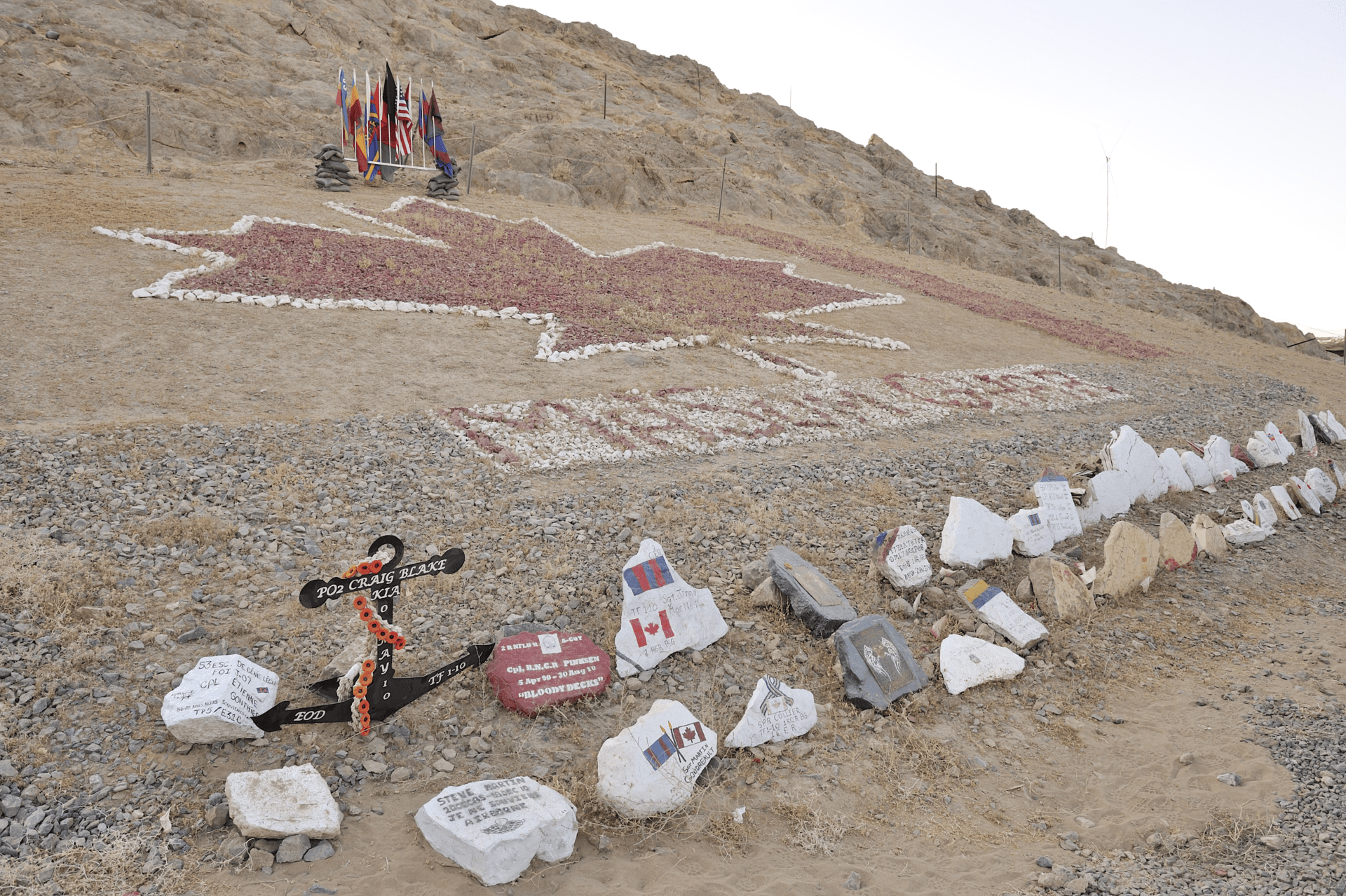

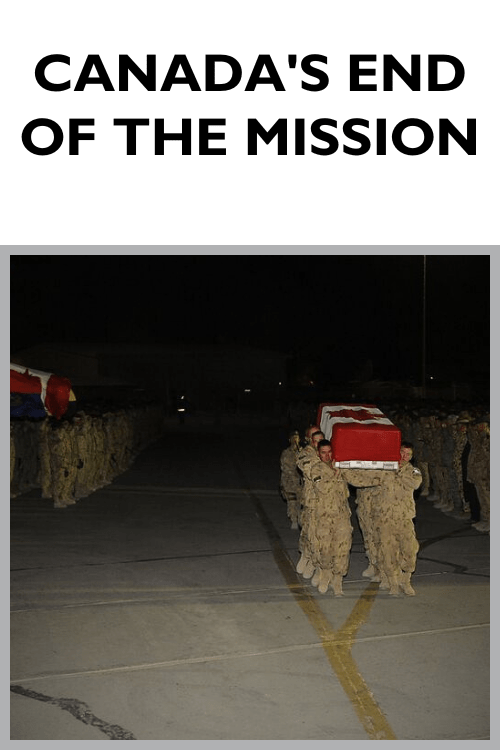

NATO Coalition Force Casualties

For those living at KAF during the years 2005-2011, NATO casualties were a tragic and visible part of life. For every coalition member killed, a repatriation ceremony would be held. These were often called “ramp ceremonies” because soldiers would line up on the tarmac to salute their fallen comrade before the body was wheeled up the ramp of an airplane to be brought home. Though Canadians at KAF were only obligated to attend ramp ceremonies for Canadian soldiers, they often attended the ceremonies of other countries as well out of respect for the fallen. In all 3,576 NATO soldiers were killed as part of the mission in Afghanistan; among them were 159 Canadians.

Civilian Casualties

Afghan civilians suffered tremendously from the war that unfolded in their cities and towns. The Costs of War project estimates that over 46,000 Afghan civilians died during the 20-year conflict and many more were injured or displaced. Civilian deaths were the direct or indirect consequences of both insurgent and US/NATO actions.

In December 2009, a suicide bomb attack in Kabul targeting an Afghan government aide killed eight people and injured 40 others. In this photo, this woman is being evacuated by a member of the Afghan army and a security guard. Suicide bomb attacks were common and were a way for insurgents to continue fighting in major Afghan cities.