Coming Home and Reintegrating Society

The First World War had a profound impact on Canadian society and, in many ways, changed it forever. The fighting may have ended in November 1918, but it took many months to bring the hundreds of thousands of Canadians overseas back home. When they arrived, they brought with them not only the scars of battle, but a deadly pandemic, the so-called Spanish flu, which ravaged Canada and left many dead. Those who survived reintegrated into a transformed society, rife with political change and also new opportunities for women. Black, Indigenous and Asian-Canadian soldiers who had served overseas returned, however, to a society that did not fully recognize their sacrifice and did not accord them the equal rights with other Canadians.

Today, however, we honour all Canadians who served in the First World War and subsequent wars. The ways in which we remember them stem directly from the First World War and are a reminder of how important the heritage of WWI remains for modern Canada.

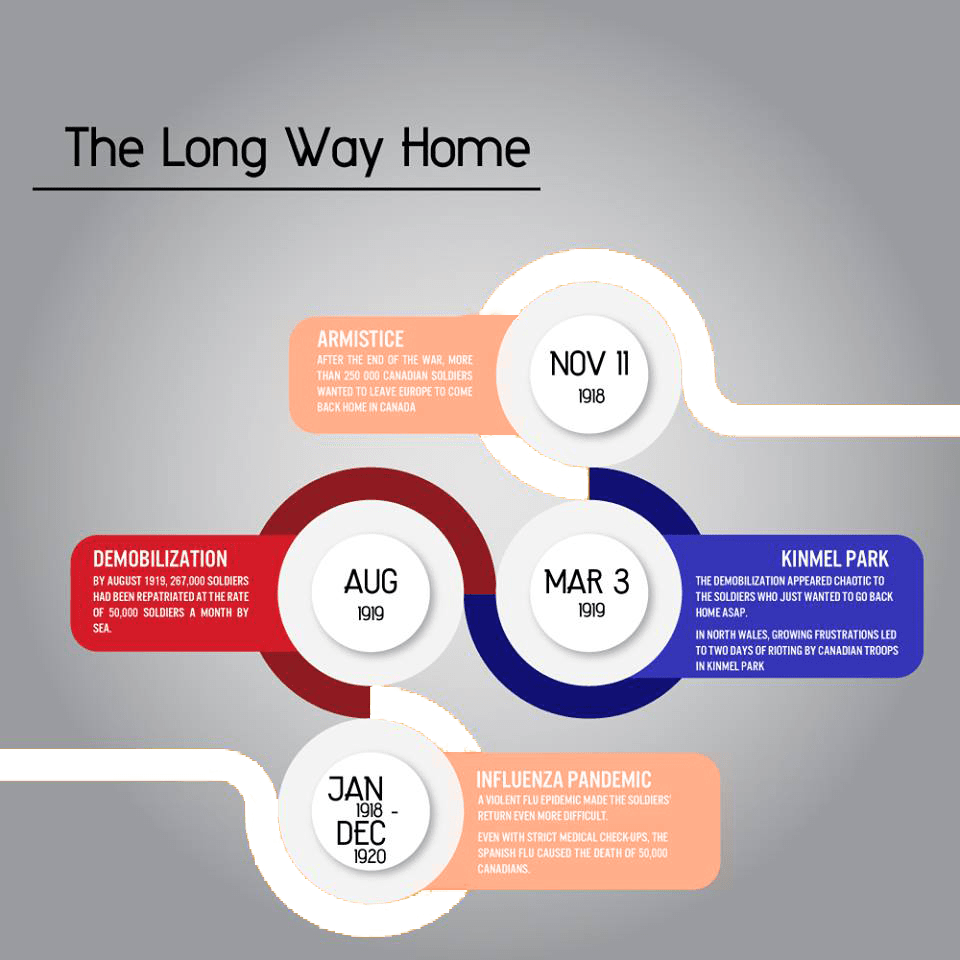

Demobilization

When we tell the History of the Great war, the story often ends with the Armistice on November 11th, 1918.

In reality, the story continued far longer for the Canadian troops who were still far away from home. The ships that were used during the war reverted to their original function of transporting commercial products instead of troops. In this context, the logistics of bringing more than 250,000 people back to Canada was a considerable challenge.

It took nine months before Canada had brought everyone back home. During this time, soldiers were restless and impatient to go back to their civilian lives after having spent so much time away overseas. Some even rioted at a holding camp (Kinmel Park) in March 1919, which resulted in the deaths of several Canadian soldiers.

Shifting Roles for Women

The years surrounding the Great War were also a tumultuous time for women. Women began to gain greater economic independence and political opportunities. Legal changes allowed women to own property, control their own finances and sign contracts and wills. Furthering their education became widely possible and many women seized the opportunity to work outside the home.

Nurses

During the Great War, over 2,500 Canadian women answered the call to arms and enrolled as Nursing Sisters. Just like their male counterparts, they were “in the army” as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). Soon enough, being a nurse became a respectable path and many women flocked to serve their country this way. In 1917, nurses stationed in Europe were the first Canadian women to vote in a federal election because a parliamentary exception – emanating from the conscription crisis – was enacted to bring them to the ballot box.

Suffragettes

The movement advocating for women’s right to vote rose in the mid-19th century, a time when women did not have a full citizenship status and were not allowed to vote. Suffragettes protested against this discrimination and campaigned for change, because they could not vote directly to change the laws that would allow them to be seen as full citizens. Before World War I, Scotland Yard considered suffragette campaigns to be a greater threat than the IRA, due to numerous acts of terror and violence committed by suffragettes across the United Kingdom.

Traditional

Not all women were in favour of radical social transformation and did not necessarily believe that the emancipation of women was a positive change for society. Anti-suffragette movements existed in Canada and many were proponents of maternal feminism, an ideology that promotes the distinctive role of women as caregivers and supports their complete freedom within the household.

Workers

Although women being paid for work was not a new phenomenon in 1914, it became increasingly normal as positions were vacated by men who left for the front. During the war, women filled factories, civil services, and participated actively in wartime industries, such as the production of ammunition. As men returned, the original status-quo was re-established, but it created a precedent where women worked in areas generally reserved for men. The genie was out of the lamp.

Remembering

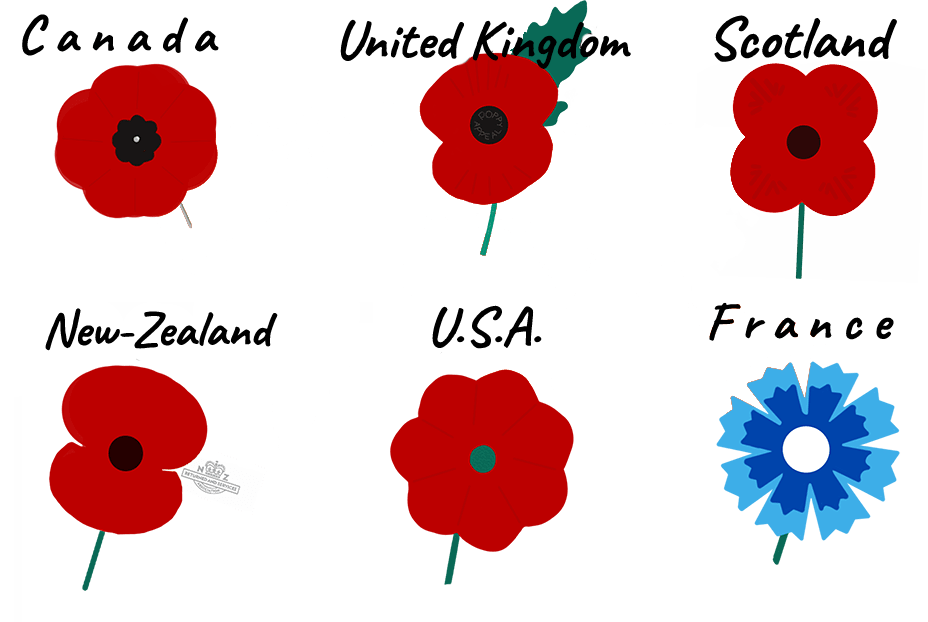

What’s a Poppy?

Papaver rhoeas, known as the common poppy, is an annual flower that blooms in late spring in Europe. The flower thrives where the soil is disturbed. Due to the continuous bombardments in Belgium and other battlefields, the red poppies were a prominent feature near the trenches and over the soldier’s graves.

Did you know that the pollen of papaver rhoeas causes no allergic reaction via inhalation?

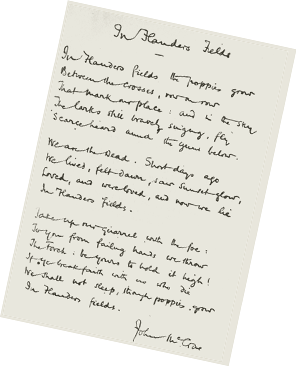

John McCrae’s Poem. May 1915

Inspired by the sight of the poppies, Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, a Canadian Medical Officer, wrote a short poem during the Second Battle of Ypres soon after the death of a close friend. McCrae was not very proud of his poem but was encouraged by friends to send it for publication.

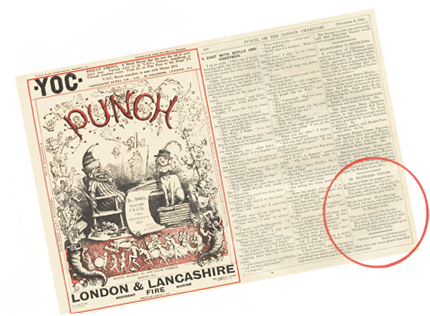

Punch Magazine, December 1915

Punch, or the London Charivari, was a British satirical publication focused on short articles, poems and small print. Prior the war, Punch was a well-established and very popular magazine. In December 1915, they decided to publish John McCrae’s 13-line poem.

Did you know that Punch Magazine published anti-war content prior to World War I? Quickly after the beginning of the conflict, the magazine did not publish anti-war statements and became very supportive of the war effort.

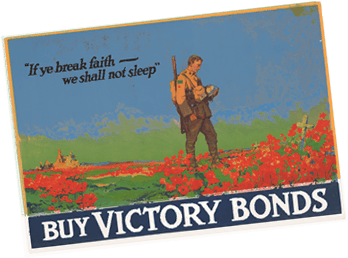

Recruitment tool, 1917

John McCrae’s poem and the image of poppies were often used in propaganda posters to sell war bonds and for the recruitment effort. This was especially true in Canada, as the country was going through the conscription crisis and needed a symbol of perseverance.

Moina Michael, 1918

An American teacher, Miss Moina Michael, was touched by reading John McCrae’s poem and vowed to wear a red poppy as a remembrance symbol for those who served during the war. She was teaching wounded veterans at the University of Georgia at the time and realized that there was a financial need to support these men, so she started raising funds by selling silk poppies.

Madame Anna Guerin was inspired by this initiative during a visit to the United States and brought the idea back to France where she directed multiple campaigns to help widows and orphans of the war.

Veterans’ Associations, 1921

The ancestor of the Royal Canadian Legion, the Great War Veterans’ Association of Canada, made the poppy their official remembrance symbol in July 1921. The same year, the Royal British Legion ordered 9 million poppies to sell on Armistice Day (November 11th). In both countries, the poppy campaign was a success and the profits went to support veterans of the war.

White Poppy, 1926

After the popularization of the red poppy in the Commonwealth, pacifist movements in the United Kingdom started to use a white version of the traditional remembrance poppy to promote the hope of a world without war. Today some anti-war organizations support the White Poppy Movement, but its popularity has diminished because its meaning is perceived as a lack of respect for the veterans and those who paid the ultimate sacrifice.

Today

Red poppies are worn on lapels every year in Canada from the last Friday in October until November 11th to remember all those who died in combat, including, but not limited to, those who died during World War I. They can be procured from the Legion during this period in exchange for a donation to help support veterans. Poppy Appeal Campaigns are usually the biggest fundraising activities of legion organizations. Based on an act of Parliament on June 30, 1948, only the Legion has the authority to sell poppies and is “entrusted by the people of Canada to uphold and maintain the Poppy as a symbol reminding us to never forget the sacrifices Veterans made to protect our freedom.”