The Birth of the Battalions

Recruitment

Canadians first enlisted in WWI out of patriotism, the desire to fight the Germans, or for the adventure of international travel. Newspapers, posters, clergymen and politicians encouraged men to enlist as a duty to King and Country.

All Canadians were expected to do their part in supporting the war.

The word “coward” was used to shame men who did not enlist.

Some posters were directed towards women to push their husbands and children to enlist.

The Government of Canada needed more men to fight and even lowered the requirements to enlist, allowing minorities to enlist as of 1916. Asian, Indigenous and Black Canadians were not allowed to enroll before that. Even though they obtained the right to fight for their country, the fight for equality for racialized people was far from over after the war.

Montreal and Westmount, early 1900s

Originally named the Village of Notre Dame de Grace in 1874, it became the Town of Cote Saint-Antoine in 1890 before being officially renamed Westmount in 1895.

Between 1876 and 1890 the population of Westmount grew from 200 to 1,850 people. By the early 1900’s there were just over 500,000 people living in Montreal. Westmount’s population at that time included financiers, wealthy businessmen and their families, many of whom lost their sons in WWI.

More than 1,500 Westmounters volunteered for WWI, many with the RMR and other units.

Westmount, 1914. There was a fear of spies in the city, leading officials to ask the population to close all public wireless stations.

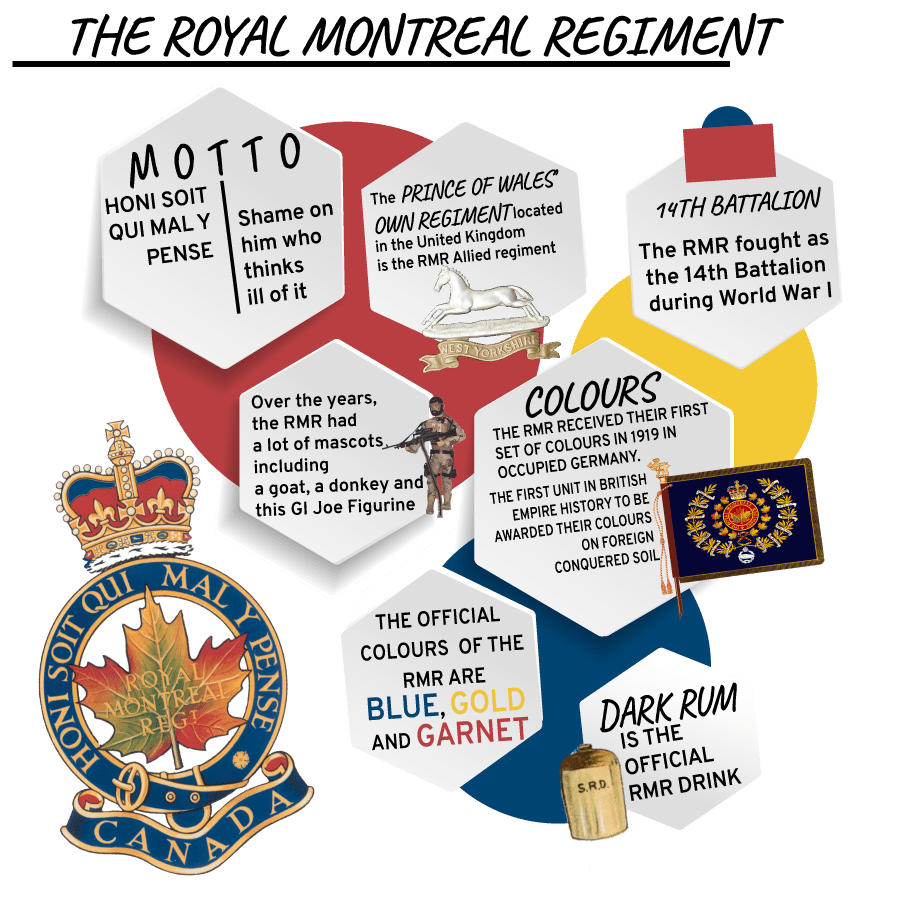

When war broke out, many Montrealers wanted to do their part to fight the enemy and answered the call to arms with enthusiasm. To coordinate the city’s war effort, the Royal Montreal Regiment was created in early August 1914. At that time it was called the “1st Regiment, Royal Montreal Regiment” and it was formed by combining three existing prominent militia regiments in Montreal: The 1st Regiment, Canadian Grenadier Guards (372 men and 12 officers); The 3rd Regiment, Victoria Rifles of Canada (355 men and 12 officers), and the 65th Regiment, Carabiniers Mont-Royal (276 men and 8 officers).

Shortly thereafter, the Minister of Militia created the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) so that all of the 424,000 Canadians that went to France and Belgium between 1914 and 1918 were part of the same centrally organized force. Within this military organization, The Royal Montreal Regiment was known as the 14th Battalion (RMR) CEF.

Composed of both English and French speaking men, the RMR “illustrated more than any other battalion in the 1st Canadian Division the spirit of unity between those two great races.”

Timeline

AUGUST 6: Active recruiting for the RMR begins

AUGUST 8: Valcartier (north of Québec City) is designated as the training base for the CEF

AUGUST 18: 983 men and 32 officers depart Montreal as The RMR

AUGUST 22: The RMR is ordered to Valcartier

Two Members of the RMR Receive the Victoria Cross

Captain Francis Scrimger

Francis Alexander Caron Scrimger was born in Montreal in February 1881 and attended Montreal High School before studying medicine at McGill University. Francis was bilingual and spoke both English and French. He enlisted in September 1914 and joined the 14th Battalion (RMR) as their Medical Officer.

Captain Scrimger took part in the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, during which he earned the Victoria Cross.

“On the afternoon of 25th April, 1915, in the neighbourhood of Ypres, when in charge of an advanced dressing station in some farm buildings, which were being heavily shelled by the enemy, he directed under heavy fire the removal of the wounded, and he himself carried a severely wounded Officer out of a stable in search of a place of greater safety. When he was unable alone to carry this Officer further, he remained with him till help could be obtained. During the very heavy fighting between 22nd and 25th April, Captain Scrimger displayed continuously day and night the greatest devotion to his duty among the wounded at the front.”

Captain Scrimger lost a finger after contracting an infection during an operation. Once he recovered from his amputation, he continued caring for the wounded in various military hospitals until he returned to Canada in 1919. He later became the chief surgeon at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal until his death in March 1937.

Lieutenant George B. McKean

George Burdon McKean was born in 1888 in England. He immigrated to Canada at the age of 14, after the death of his parents, and moved to Lethbridge, Alberta where he worked as a farmer. He tried to enroll three times prior to January 1915 and was turned down, most likely because his height did not meet the requirements. Ironically, when he was eventually allowed to enlist, his small stature made him a very good scout, and he was able to travel through no man’s land without being spotted by the enemy.

Lieutenant McKean received the Victoria Cross for his action in the Gravelle sector in April 1918.

“For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty during a raid on the enemy’s trenches. Lt. McKean’s party, which was operating on the right flank, was held up at a block in the communication trench by most intense fire from hand grenades and machine guns. […] Realizing that if this block were not destroyed, the success of the whole operation might be maraud, he ran into the open to the right flank of the block, and with utter disregard of danger, leaped over the block head first on top of the enemy. […] This officer’s splendid bravery and dash undoubtedly saved many lives, for had not this position been captured, the whole of the raiding party would have been exposed to dangerous enfilading fire during the withdrawal. His leadership at all times has been beyond praise.”

Shortly after the war, McKean was part of the administration of the Khaki University of Canada. He then moved to Brighton, England, where he got married and operated a sawmill. In November 1926, he was killed in a workplace accident when a saw blade broke and the pieces flew into his head.

Who are the French Canadians?

The term “French Canadian” refers to the inhabitants of Canada whose mother tongue is French. Their ancestors generally come from France.

In 1911, Canada had seven million inhabitants, a third of whom were French Canadians. Most of them lived in Quebec, the only predominantly French-speaking province. Other French-speaking communities of varying sizes could be found across the country, but they were a minority.

Towards the end of the 19th century, French-Canadian society was largely homogeneous. The Catholic religion was omnipresent, and the majority of people lived in the countryside. An economic crisis and a scarcity of agricultural land caused an exodus of French Canadians to the cities, but also to the United States. Nearly one million French-speaking people left to find work on the other side of the border.

A series of incidents dating back to the 1870s had strained the relationship between Francophones and Anglophones. Measures to prohibit the teaching of French in schools were introduced in several Canadian provinces. This caused indignation in Quebec, where people had not forgotten the hanging of Louis Riel in 1885. Riel was a defender of the rights of the Métis, a people with a mixture of Indigenous and European, mostly French, ancestry. Many Métis spoke French and Francophones across Canada were bitter about his murder. They also remembered the Patriots’ rebellion and the Durham Report that followed with bitterness.

French Canadians had been in North America for several generations and did not feel any particular loyalty or proximity to Europe, the land of their distant ancestors. On the contrary, many English-speaking Canadians were the first or second generation of their family in the country and felt affected personally by the conflict. Nevertheless, it was clear to both groups that the conflict was global in nature. Criticisms regarding the low level of participation of Francophones in the war effort were upsetting. Wanting to prove their patriotism, a Francophone delegation was formed and they officially requested the creation of a French-Canadian battalion in front of the Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden on September 28, 1914, in Ottawa.

Arthur Mignault, a doctor who had made his fortune in the pharmaceutical industry and who was Major Surgeon of the Mont-Royal Carabinieri Militia, ancestor of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal de Montréal, offered $50,000 of his personal fortune to create and equip a French-speaking Battalion. He wanted a Battalion that could bring together French Canadians across the country and even Franco-Americans residing in the United States. In 1914, $50,000 was a colossal sum!

These initiatives were publicized by the newspaper La Presse, whose managing editor, Lorenzo Prince, supported the cause. La Presse called for the formation of a French-speaking unit from the beginning of the war and the paper remained a valuable recruitment tool. A crowd of about 20,000 people gathered to hear the speeches of the French-Canadian delegation in favour of the creation of a French-speaking military unit.

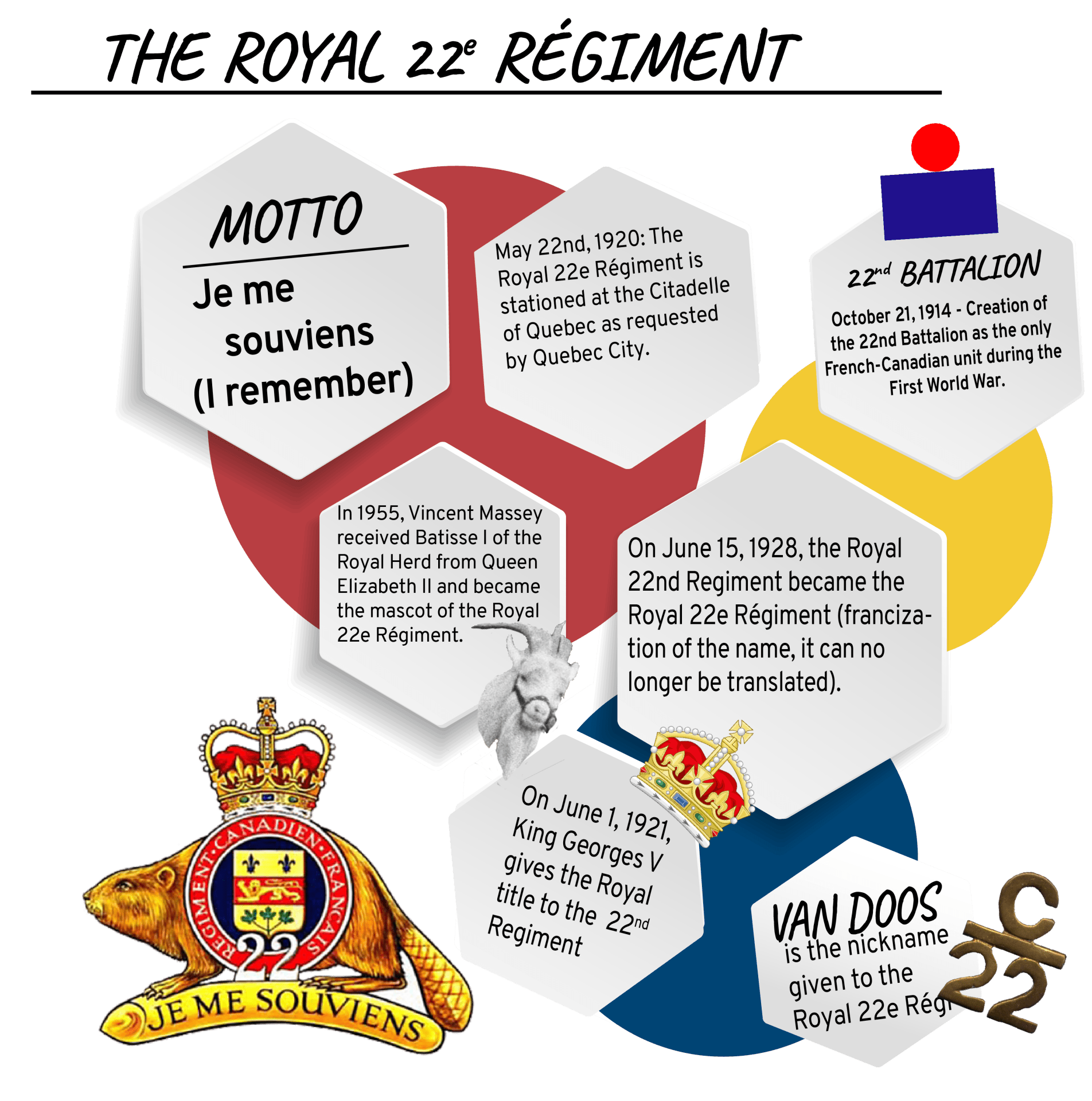

Faced with such a strong movement, Borden agreed to the creation of a French-speaking infantry battalion. On October 21, 1914, it was created as the Royal French Canadian Regiment. Since the battalions that were integrated into the Canadian Expeditionary Force were numbered, the Regiment was given the number 22. And thus the 22nd French-Canadian Battalion was born!

The 22nd Battalion in Training

It was in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, on the south shore of Montreal, that the first 1000 volunteers of the 22nd Battalion were introduced to military life: handling weapons, exercises and long marches. Cramped in the barracks of a cavalry unit, squalor and boredom led to desertions. The newspaper La Presse encouraged citizens to send games and books. It even organized a visit by train to Saint-Jean for families during the holiday season.

March 1915: In need of better facilities, the 22nd Battalion left for Amherst, Nova Scotia. The small English-speaking town offered only a cold welcome. During its stay, however, the 22nd Battalion became involved in the community, and demonstrated exemplary conduct. Prejudices fell and the town was sad to see the 22nd Battalion leave two months later.

After a ten-day voyage aboard the ship HMT Saxonia, the 22nd Battalion crossed the Atlantic and arrived at a training camp in East Sandling, England on on May 30, 1915 . These were the last training exercises before leaving for the front. In spite of their extensive training, the arrival on the front lines was to be a real shock.

Where does the nickname“Van Doos” come from?

Given to the battalion during the First World War, this nickname comes from a distorted pronunciation of the number “twenty-two” in French by English-speaking soldiers. The nickname Van Doos is still frequently used today to designate the Royal 22nd Regiment in English.

Although the 22nd Battalion was created in response to a need for a French-speaking unit for soldiers from all over Quebec, it included members from a variety of backgrounds from its inception.

Two members of the 22nd Battalion receive the Victoria Cross

Corporal Joseph Kaeble

Born on May 5, 1892, Joseph Kaeble enlisted in the 189th Battalion on March 20, 1916. On November 13, 1916, during preparations for the attack on Vimy Ridge (France), he was transferred to the 22nd Battalion.

On September 16, 1918, he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross by the government.

He was a true hero during the battle west of Neuville-Vitasse, France, on the night of June 8-9, 1918. On this occasion, he was zealous in the performance of his duty, commanding a machine-gun section in the first line of trenches, on which a powerful raid by the enemy was attempted. When all the men in his section were wounded, Corporal Kaeble leapt out of the trench and ran straight at the enemy, emptying all the magazines of his machine gun. Repeatedly wounded by enemy fire, he fell backwards into the trench, but continued to fire on the attackers until he collapsed. His last words were, “Hang in there guys! Don’t let them get through! They must be stopped! “Seriously wounded in the legs, arms, neck and left hand by shrapnel, he died the next day, on June 9, 1918.

Lieutenant Jean Brillant

Born on March 15, 1890, Jean Brillant first studied at Collège Saint-Joseph in Memramcook, New Brunswick, and then completed his studies at the Séminaire de Rimouski. He enlisted in the 189th Battalion on January 11, 1916.

On October 27th, 1916, he went to France and joined the 22nd Battalion (French-Canadian), stationed in the northeast of the country. During the clashes in Amiens, France, he was wounded in the left arm as he single-handedly eliminated two machine gunners. Refusing to be evacuated, he continued the fight on August 9, 1918, this time leading two platoons in a terrible bayonet and grenade fight. With the help of his men, he captured 15 machine guns and took 150 prisoners. Wounded in the head, he still refused to be evacuated. The next day, while leading an attack against a cannon that was raining down on his unit, he was seriously wounded in the abdomen by shrapnel. On August 10, Lieutenant Brillant died of his wounds at the age of 28. His body is buried in the military cemetery of Villers-Bretonneux, 15 km east of Amiens. For his exceptional bravery and tireless zeal in the performance of his duty, he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, the Commonwealth’s highest honour.

Test Your Knowledge!

Some Statistics

A large quantity of food was needed to feed all these soldiers. Not only did we have to equip them to be ready for battle, we also had to feed them!

Horses were used for logistical support to bring supplies to the front because they were more reliable than vehicles, especially in the mud.

In fact, approximately 256,000 horses and mules perished alongside the Commonwealth armies on the Western Front.