Thousands of Indigenous, Métis and Inuit people enlisted in the Canadian army during the Great War. In Europe, many of these men were scattered from one unit to another. In 1915, however, the Canadian government authorized the creation of a dedicated unit for indigenous people: the 107th Battalion (Winnipeg), CEF, nicknamed the “Timber Wolf”. Deployed to Europe, the men of the battalion immediately proved their worth.

Many Indigenous soldiers have been celebrated for their military service in the Canadian Army during the First World War. Indigenous enlistees such as John Shiwak, Francis Pegahmagabow and Henry Norwest are frequently lauded for their past military feats and—if they survived the war—contributions to their communities

With the outbreak of the First World War, the 107th Battalion (Timber Wolf) was one of two Canadian units—the other being the 114th Battalion (Haldimand)—that were comprised mainly of Indigenous and Métis troops. As the Haldimand mainly acted as a reserve unit, the Timber Wolf was the only battalion of its type to see action in Europe. The members of the 107th showed outstanding dedication to duty throughout their war service, from Vimy Ridge to Hill 70.

Recruiting Indigenous, Métis and Inuit men at the start of the Great War

Unsurprisingly, the Canadian army initially did not allow recruits from non-White ethnic communities. Many officers at the time thought war was an affair for White men only and, if possible, for Anglophones only as well. Since people from Indigenous communities wanted to join the army for different reasons, they found ways to enlist despite these discriminatory policies.

It is unclear how many Indigenous, Métis, and Inuit volunteers served in the army overall. At the time, recruits only had to state whether they were from an Indigenous nation that had signed a treaty with the federal government. Based on this data, an estimated 4,000 “status Indians” enlisted. However, this number is probably much higher if Métis and Inuit recruits—like sniper John Shiwak—are included. The British Empire only began to actively recruit Indigenous soldiers in 1916, or after its armed forces had sustained terrible losses. The need for recruits in this case outstripped the entrenched mindset of institutional racism.

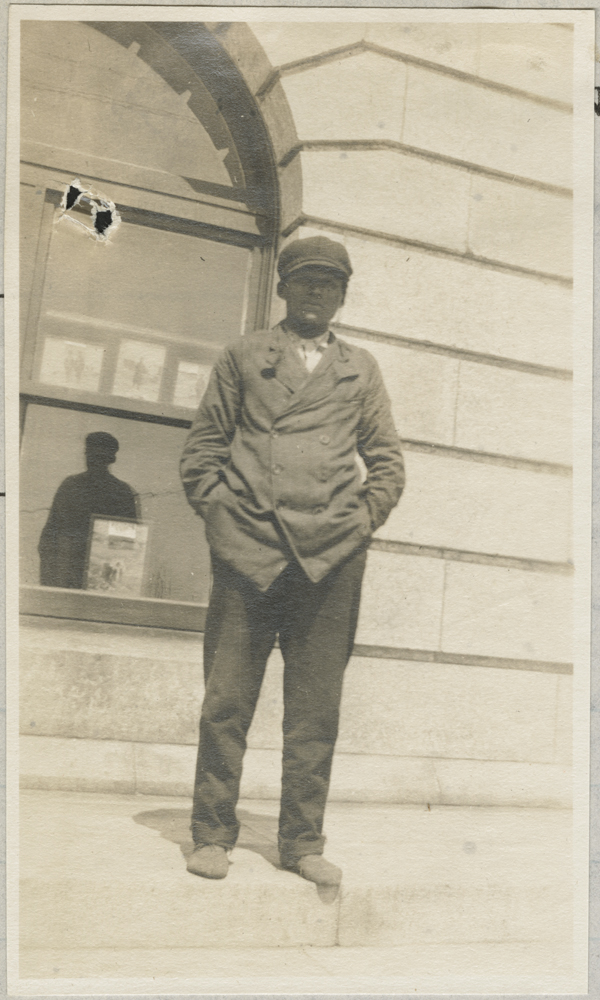

Left: Portrait photo of sniper Michael Ackabee. Originally from the Wabigoon nation, he fought with the 28th Battalion (Northwest) during the war.

How an Indigenous unit was founded

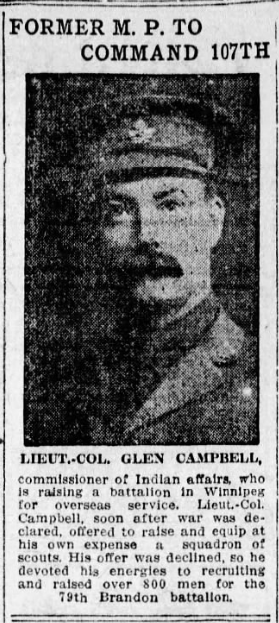

A year earlier, in 1915, Conservative politician and White settler Glenlyon Campbell began lobbying the government to form a unit of Indigenous soldiers. Hailing from a wealthy Manitoba family, Campbell had interacted with many of the province’s Indigenous nations in different contexts.

During his childhood, Campbell was sent to Scotland to study and, according to his father, escape the first rebellion led by Métis leader Louis Riel (1869-1870). When he returned as an adult, Campbell joined the Canadian militia to fight Louis Riel’s second rebellion in 1885, and he received the rank of captain in return for his service.

However, Campbell’s relationship with the Manitoba tribes was not only an armed contentious one, as many Indigenous communities sided with the federal government during Louis Riel’s rebellions. As a cattle rancher, Campbell maintained ties with Indigenous people through these communities. Over the years, he learned different Indigenous languages, such as Cree and Ojibwe, and even ended up marrying a daughter of Chief Keeseekoowenin named Harriet Burns.

In November 1915, Campbell received the government’s go-ahead to form a Europe-bound unit called the 107th Battalion (Winnipeg). Thanks to Campbell’s initiative, the battalion became a de-facto unit of mainly Indigenous people from the Manitoba region. Campbell capitalized on his reputation to recruit volunteers. While travelling from Nation to Nation, he would visit residential schools to recruit boys who had not even reached the age of majority. As he wrote at the time:

“Were those lads with me, they would be under closer and more kindly supervision than in any other Battalion in the west… even if they were not quite eighteen years of age.” (source)

While his reasons for recruiting Indigenous boys do not minimize the horrible conditions at the residential schools, Campbell seemed to use a common British recruitment tactic at the time. During the war, many British officers visited high schools to encourage boys who were about to become of age to join the army. At Anglophone schools in Canada, teachers would also encourage their students to join the war effort by suggesting that they run food drives or fundraisers, put on shows or ceremonies, work in the fields, or simply enlist in the army.

Before long, over 1,700 people from Manitoba’s various Indigenous nations applied to join the Timber Wolf. Campbell turned down 600 of these applicants and kept the best people to train as his first officers and soldiers.

At first, the battalion was made up of half White soldiers and half Indigenous soldiers, the majority of whom came from different ethnic groups that had settled in Manitoba, such as the Niitsítapi (or “Blackfoot,” as they were called by White settlers), Cree, Ojibwe, Haudenosaunee and Dakota. Many of these new volunteers could not speak even basic English and had to take training to comply with the British army’s requirements.

Tom Longboat (1886-1944)

One recruit transferred to the 107th was the world-renowned Olympic runner Tom Longboat. From the Onondaga community of Six Nations of the Grand River, Tom (given name Gagwe:gih) had no reason to join the army, as his running career was very lucrative and he had just married school teacher Lauretta Maracle. Despite everything, he felt compelled to go off to war. With the 107th, Longboat was made a dispatch rider, or a soldier who carried messages from place to place—which put his running skills to good use! Although wounded twice, Longboard managed to survive the war.

Left: Private Tom Longboat, far right, in a trench in France, 1917 (source: Library and Archives Canada).

Military service in Europe

Campbell’s men arrived in Europe on October 25, 1916, after completing their basic training in Manitoba. As could happen with any other unit, troops started transferring in and out of their battalion once they arrived. In this case, however, the new arrivals were mainly Indigenous soldiers while White soldiers left for other units. At one point, the army considered disbanding the Timber Wolf completely and spreading the soldiers among other battalions. However, Campbell categorically refused, arguing that his men would be treated badly in the White units.

When it arrived in Europe, the unit was designated as a Pioneer Battalion, or a battalion whose troops trained as both infantry and engineers. At the front, these soldiers had to build trenches, shelters, fencing and railroads as well as transport munitions. Their duties also included taking part directly in combat operations.

Soldiers in the Pioneer Battalions had to carry a lot more equipment than typical infantrymen. On top of their weapons and regular equipment, they had to lug around all of their construction tools, including wooden planks and barbed wire!

The Timber Wolf’s first major feat of arms was at the Battle of Vimy Ridge, from April 9 to 12, 1917. One of the greatest battles in Canadian military history, Vimy Ridge was also the first time that the entire Canadian army fought as a single, united force.

In August of that year, the 107th also showed particular bravery during the Battle of Hill 70, where its first task was to dig new trenches as quickly as possible—all while taking enemy fire and shelling. The Timber Wolf members went above and beyond as, after intense fighting, they volunteered to retrieve the wounded from No Man’s Land. They managed to save 25 soldiers and recover the bodies of 30 more but at a terrible price: the Germans released gas on them, poisoning 88 soldiers. Out of all troops sent to the Hill from the battalion, 21 were killed and 140 were wounded.

A unit that changed minds

Glenlyon Campbell died at the front on October 20, 1917 from a wound combined with an existing medical condition. The 107th continued to fight at the front under a new commander until it was disbanded on May 28, 1918.

While the discrimination they faced did not end with the war, the military service of the Timber Wolf soldiers changed the perception of many of their White comrades. As noted by historian Steven A. Bell, no disciplinary infractions or sanctions were ever lodged against the Timber Wolf Battalion. This was a sign that, despite serious initial obstacles, these soldiers were motivated, disciplined, and held in high esteem by their peers.

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens.

Sources:

- “107th Timber Wolf Battalion“, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “107th (Timber Wolf) Pioneer Battalion“, The Canadian Military Engineers Association.

- “CAMPBELL, ARCHIBALD GLENLYON“, Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- “Indigenous contributions during the First World War“, Gouvernement du Canada/Government of Canada.

- “Lieutenant Colonel Glenlyon Campbell“, Mémorial virtuel de guerre du Canada/The Canadian Virtual War Memorial.

- “Tom Longboat“, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

For a more academic approach:

- Steven A. Bell, “The 107th “Timber Wolf” Battalion at Hill 70“, Canadian Military History, vol. 5, no. 1, 1996, pp. 73-78.

Finally, Library and Archives Canada has digitized a number of archival documents relating to Aboriginal participation in the Second World War:

- War 1914-1918 – Enlistments and War Activities of First Nations (Photos of First Nations Soldiers).

- War diaries – 107th Pionneer Battalion.