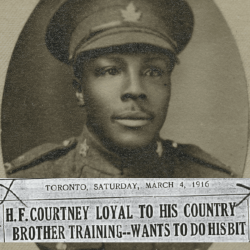

Jacob Courtney

Jacob Courtney was born in Owen Sound, Ontario in 1876 to Carrie Parker and Abraham Courtney, a freedom seeker who escaped slavery along the underground railroad. Unfortunately, both Carrie and Abraham passed away in the 1890s leaving Jacob’s older sister Ethel to look after her younger siblings. When the war broke out, Jacob was living in New Lowell, Ontario with his son John. Jacob’s wife, Rachel, died shortly after childbirth in 1908, leaving Jacob to look after John alone. To support his son, Jacob worked as an interior designer. Jacob attested on December 1, 1915 with the Simcoe Foresters. However, the commanding officer did not approve and sign Jacob’s papers until February 1, 1916. Before leaving for overseas, Jacob brought his young son to live with Esther and her husband John Carter in Guelph. One could imagine how difficult it must have been for Jacob to leave his son at a young age, but Jacob obviously felt compelled to help with the war effort.

Sailing alongside other members of the 157th Battalion on the SS Cameronia, he arrived in England on October 28, 1916. In 1918, he transferred to the 4th Canadian Battalion and participated in the battle of Canal du Nord as part of the 100 Days Offensive. He survived the war and was awarded a Good Conduct Badge for his service.

Jacob was not the only member of the Courtney family who wanted to join the war effort, however. Born in 1883, Jacob’s brother Henry worked as a teamster in Owen Sound and wanted to enlist like his older brother had before him. Henry tried to enlist several times but, unlike his brother, was not able to find a battalion that would take him. This changed with the creation of the No. 2 Construction Battalion.

An All-Black Platoon

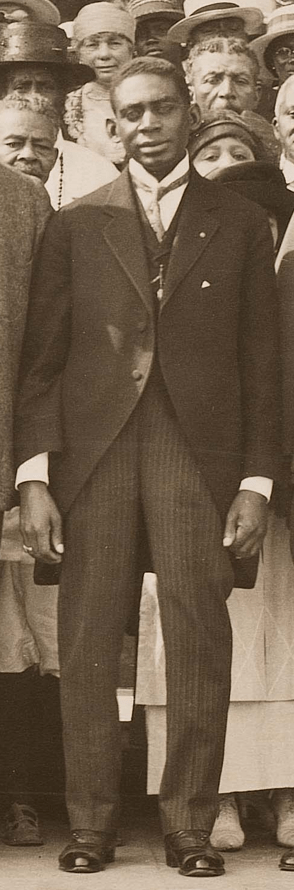

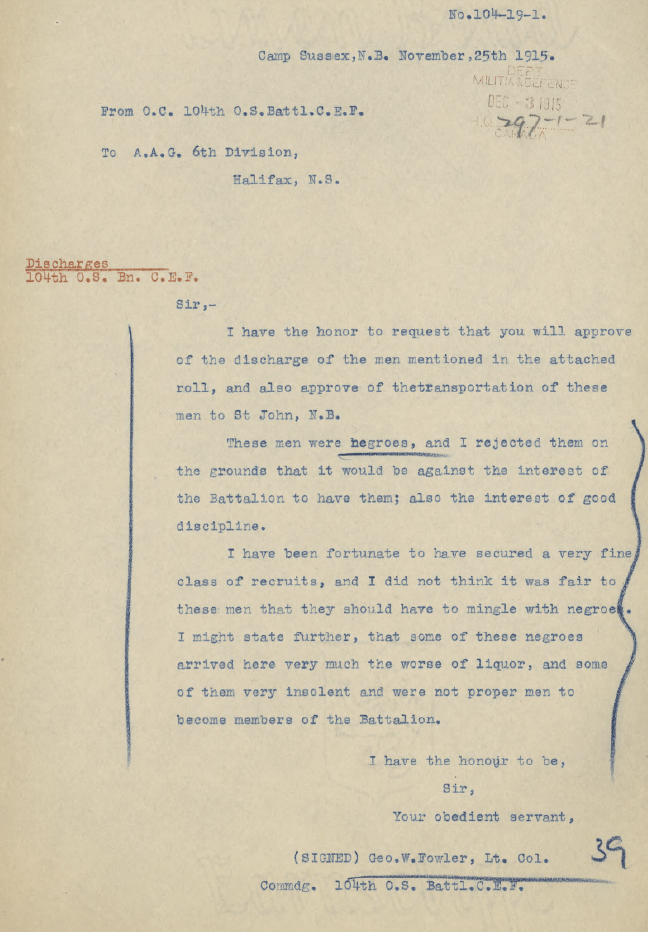

Frustrated by the racism of recruitment officers and their lack of acceptance, Black Canadians across the country began to petition the government to create all-Black battalions or platoons. In Toronto, local publisher J.R.B. Whitney began recruiting citizens with the hope that the Canadian government would allow him to create one such platoon. On November 24, 1915, he appealed to Sir Sam Hughes, the Minister of Militia, asking permission to create a platoon of 150 men from Toronto, London, St. Catherines, Chatham and Windsor. In response, Hughes stated “I beg to advise you that these people can form a platoon in any battalion, now. There is nothing in the world to stop them”. Excited by the news, Whitney began the process of recruiting men through his newspaper The Canadian Observer.

Many interested men contacted the offices of the Canadian Observer to volunteer, including Henry Courtney. Excited by the prospect of finally being able to enlist, Henry wrote a letter to Whitney stating, “If you can please find time to sit down and write me a few lines to let me know if I can join, I will be deeply in love with you”.

By April, Whitney had recruited nearly 40 men for his platoon. However, unknown to Whitney, as individual enlistment was still up to the discretion of commanding officers, the platoon could only go ahead if a commanding officer would accept the segregated platoon. Whitney soon received a letter stating that since no commanding officer was willing to accept a coloured platoon into their battalion, he should stop recruiting. Although no reason was explicitly given to Whitney, internal memorandums from the military confirm that this was due to the racist attitudes held by military officials. One document, dated April 13, 1916, even argued Black men would make bad soldiers, and that white soldiers would not want to associate with them, nor reinforce them in battle. Enraged by the news, Whitney took action, increasing his efforts to convince the government to reconsider. He sent articles from the Canadian Observer to Hughes to show the interest in the platoon by the Black community and to demonstrate the patriotism of Black Canadians. One article included an excerpt from the letter written to Whitney by Henry Courtney. In the letter Henry said that he wanted to be able to help the war effort and stated that he was “hearty and strong, never have I been sick, I am working in the bush.” Unfortunately, the government again refused to find a place for the platoon.

Henry Courtney and the No. 2 Construction Battalion

Although Whitney’s plan did not come to fruition, the continued pressure by Whitney and other individuals across Canada caused the military to reconsider finding a place for Black soldiers in Canada’s military. It is important to note that by 1916, volunteer recruitment had drastically fallen, and the military needed soldiers. Military officials decided to create an all-black labour battalion and authorized the No. 2 construction battalion on July 5, 1916. The battalion was based out of Nova Scotia and although most of the members of the battalion were from that province, the battalion was able to recruit from all over Canada. Henry quickly took the opportunity and enlisted with the battalion on August 30, 1916.

Henry and the other members of the battalion were supposed to have additional military training when they arrived in England in April 1917. However, the military diary for the battalion states that their training was “subordinated to agricultural labour, mostly planting potatoes”. Henry became provisional Corporal in January 1917 and was to be officially promoted to corporal on his arrival. Unfortunately, officials reversed the decision, and he went to France as a private. This was likely a result of the restructuring of the battalion by the War Office. Since the battalion, which had 614 officers and men, was below the required size of 1,049 men, the War Office downgraded the battalion to a labour company. Henry was sent with the company to aid the Canadian Forestry Corps with construction projects in France. There they spent most of the war creating logging-related infrastructure.

After the War

Henry and Jacob Courtney survived the war, and both returned to Canada by the spring of 1919. After the war, Jacob continued as an interior decorator in New Lowell and Collingwood. He moved back to Owen Sound in 1937 and had a large family with his wife Irma. He passed away in 1957 at the age of 81. Henry passed away ten years before in 1947. Upon the news of his death, the city lowered the flag to half-mast at the Owen Sound City Hall. Jacob and Henry inspired many members of the Courtney family to enlist in the armed forces, including Jacob’s sons William, Donald, and Louis, who took part in the Second World War.

The Courtney brothers’ stories are only two examples of the strength and perseverance that Black Canadians showed during the First World War. Black soldiers not only fought on the front, but also fought the discriminatory system of enlistment at home. In 2022, the Canadian government officially apologized for its role in discrimination against Black enlistees in the First World War.

Article written by Anthony Badame for Je Me Souviens.

Sources:

To Learn More about the Courtney Brothers:

- “Black Guelph Volunteers in the Great War“, Part of the online exhibit The Black Past in Guelph: Remembered and Reclaimed.

- “Henry Courtney Personnel File“, Library and Archives Canada/Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.

- “Jacob Courtney Personnel File“, Library and Archives Canada/Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.

To Learn More about Black Canadians in the First World War:

- “Canadian Armed Forces Honour the No. 2 Construction Battalion“, Government of Canada/Gouvernement du Canada.

- “Enlistment of Coloured Men in the Canadian Militia“, Library and Archives Canada/Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.

- “War diaries – 2nd Canadian Construction Company“, Library and Archives Canada/Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.

- Sean Flynn Foyn, The Underside of Glory: African Canadian Enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1917, University of Ottawa (Master’s thesis), 2000, 154 p.