In 1942, a few months after the start of the Pacific War, thousands of Japanese-Canadians were expelled from their homes and sent to internment camps across the country. During the war, Lena Hayakawa spent most of her childhood interned with her family. A sadly common story for this community.

Thousands of Japanese Canadians were interned by the Canadian government from 1941 to 1945. This action was a direct response to the Japanese army’s attack on Western colonies in the Pacific on December 7, 1941, which showed that Japan had become a clear military threat to the Allies. Unfortunately, issei (first-generation Japanese citizens) and nisei (second-generation Japanese citizens) got caught up in the anti-Japanese sentiment and were also perceived as a threat.

This was not the first case of racism against Asian populations. Most Asian immigrants who had come to Canada since the 19th century had settled in British Columbia, and they were frequent victims of institutional and other types of racism. In Vancouver, a series of race riots that erupted between September 7 and 9, 1907 involved attacks by white people on Asian-owned businesses. Thus, when war was declared against Japan, communities of Japanese descent were again subject to a new wave of racism.

Lena Hayakawa’s story is not unusual, although we have little information about her. Aside from an interview she did with Matthew McRae for the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, Hayakawa has not often spoken publicly. Why dedicate a short article to her then? Her life events fill in some pieces about the war, as little has been written about women and even less has been about racialized women. Although her story is not extraordinary, it does reflect the wartime fate of thousands of Japanese Canadians and of many children of Japanese origin during the war.

In Canada, several former internees became well-known personalities, such as environmental activist David Suzuki and writer Joy Kogawa. However, apart from the major figures who were able to make the general public aware of their experience during the war, Hayakawa embodies thousands of invisible internees: from victims to activists. To tell her story is to tell the story of many others.

The Internment of Lena Hayakawa

In the short interview she gave to McRae, Hayakawa said that she was born in British Columbia and lived in Pitt Meadows, an agricultural town outside of Vancouver. Hayakawa’s family tended a strawberry farm before the war. They were of modest means, but they were happy, according to her.

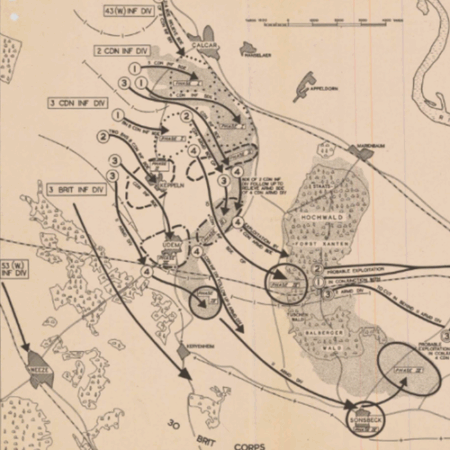

As mentioned above, the Battle of Hong Kong and the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor were turning points for Japanese communities in Canada. On February 24, 1942, Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King ordered that Japanese families be excluded from a 100-kilometer zone off the Pacific coast. As a result, over 22,000 people were deported from British Columbia and sent deep into the Canadian prairies.

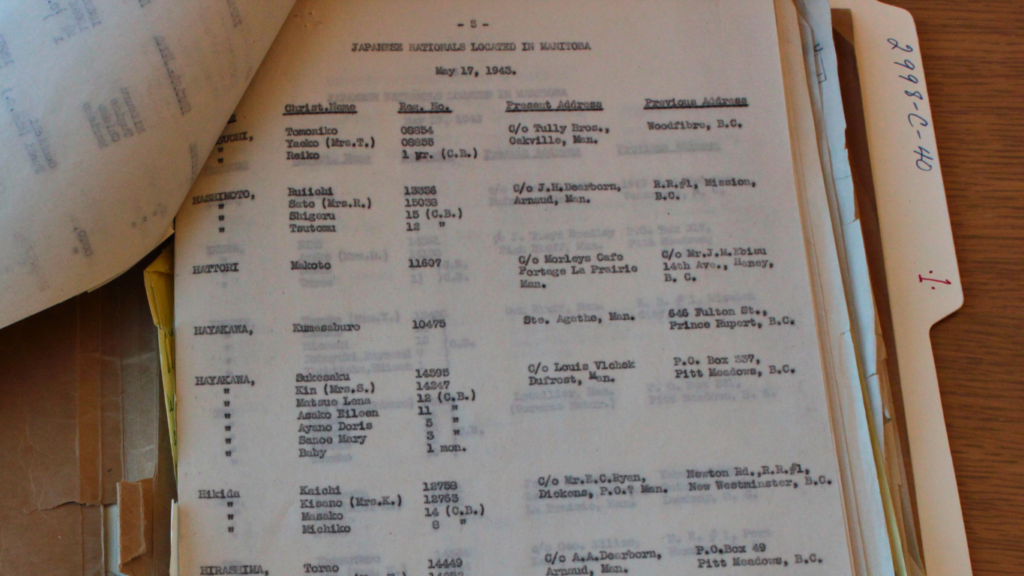

Library and Archives Canada owns thousands of archival documents relating to the internment of Japanese Canadians. During the Second World War, Japan and Canada negotiated a potential exchange of prisoners of war. In collaboration with the Red Cross, the Canadian government began to compile a list of deported Canadians.

Digging through file 2998-C-40C (Subject: “Exchange of Information RE Prisoners of War & Interned Civilians Between Canada & Japan (Including Nominal Rolls) — Arrangements RE”) we find multiple lists of Japanese Canadians who were deported outside the province. One document compiled by the federal government and dated May 17, 1943, is a registry containing Hayakawa’s family that provides more information about them. The registry contains her full name: Matsue Lena Hayakawa. It also shows that Lena was 12 years old. This means her year of birth would have been 1930 or 1931 and she would have been 10 or 11 years old at the start of her internment!

She and her family were among the 4,000 Japanese Canadians deported to Alberta or Manitoba to work in the sugar beet fields during the war. Lena was thus interned with her father, Sukesaku, her mother, Kin, and her sisters: Asako Eileen (age 11), Ayano Doris (age 5), Sanoe Mary (age 3) and a baby whose name does not appear on the document. Lena and her family took the train to Winnipeg and were then transferred to the small town of Dufrost.

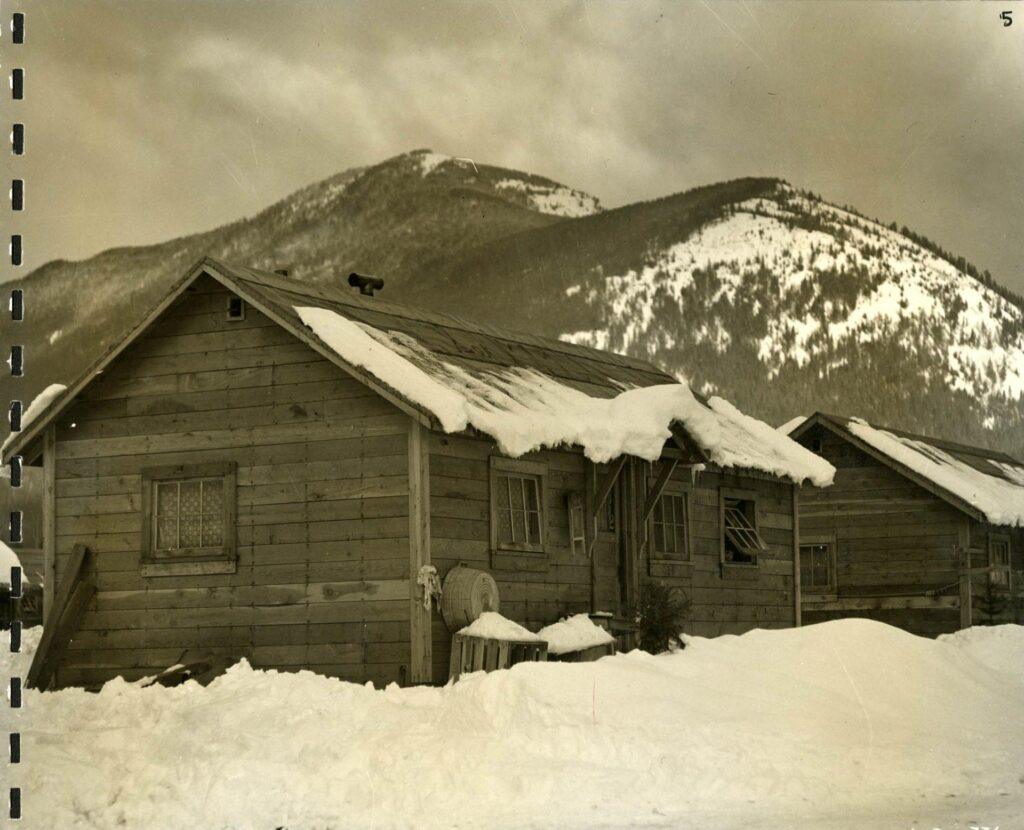

Si Lena était la plus vieille de sa fratrie, leurs jeunes âges ne les sauvèrent pas du travail ! cependant : elle témoigne ainsi que toute sa famille devait travailler dans les champs dans des conditions très difficiles. La famille Hayakawa entière était logée dans une petite cabane en bois délabrée. Lena décrit ainsi un bâtiment aux murs peu étanche à laquelle la lumière de la lune passait à travers les craques. Nous pouvons facilement imaginer les conditions difficiles que la famille devait subir à l’intérieur d’un tel logement — les hivers rigoureux comme les étés chauds et humides. Hayakawa nous donne ainsi un aperçu de ces conditions :

Although Lena was the oldest of her siblings, the children still had to work despite their young age! Lena reported that her whole family had to work in the fields under very difficult conditions. The entire Hayakawa family was housed in a small, shabby wooden shack. At night, she could see the moonlight through the spaces between the logs. It’s easy to imagine the harsh conditions that the family endured there, especially during the frigid winters and hot, humid summers. Hayakawa talked about these conditions:

“In the wintertime, there was only a wood stove… the bathroom and everything was all outside and there was no bathtub. In the wintertime, my mother had to bring the snow in the house and melt it.” (Lena Hayakawa to Matthew McRae, Canadian Museum For Human Rights).

After the Internment

After the war, Lena and her family did not return to British Columbia. The Canadian government prohibited Japanese Canadians from returning to their home province. They had two choices: settle in the Eastern provinces or be deported to Japan. The authorities pressured several thousand internees to choose but without any certainty as to what would become of them. Lena’s family chose to stay in Canada and moved to Whitemouth, Manitoba to start a new life. Their strawberry farm in BC was probably seized and sold by the government, which meant that the family received nothing for it.

The National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) was founded in 1947 in response to the internment. It sought compensation from the Canadian government and wanted to make sure that this injustice would never happen to any other Canadians.

In her interview, Lena said that she is a shy person who is not used to expressing herself. However, she said that she quickly became involved in her local NAJC and spoke frequently at their meetings. In her interview with McRae, Lena was unclear about her involvement with this organization, but she stressed that it is important for Canadians to know the tragic history of their issei and nisei neighbours so that this shameful episode of our history never leaves our collective memory.

In 1984, the NAJC submitted a brief to the government entitled “Democracy Betrayed: The Case for Redress,” which called on the government to make reparations for the internment of Japanese Canadians between 1941 and 1945. After much discussion, an agreement was reached with Brian Mulroney’s government in August 1988; shortly thereafter, the Prime Minister formally apologized to the victims of the internment. The government also offered $21,000 in compensation for each victim, provided official pardons for those wrongfully imprisoned, and bestowed Canadian citizenship on Japanese Canadians and their descendants who were deported to Japan.

For Lena, government reparations helped her open up about her past. As she explained, “When the redress came… we started to come out with all our stories for people to know what happened to us Then our children would know what happened. Otherwise, they’ll never know.” (Lena Hayakawa to Matthew McRae, Canadian Museum For Human Rights).

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translation by Amy Butcher (www.traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- “Japanese Canadian Internment“, Valour Canada.

- “Japanese Canadian Internment: Prisoners in their own Country“, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “Japanese Canadian internment and the struggle for redress“, Musée canadien pour les droits de la personne/Canadian Museum For Human Rights.