This article was published as part of our Dieppe Raid exhibit: Courage in Chaos.

View our exhibit to learn more about the sacrifice of the Canadian soldiers sent to attack the beaches of Dieppe!

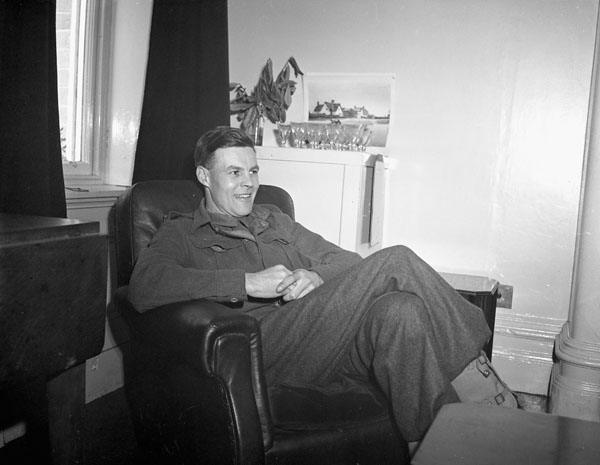

Although Dieppe was a complete disaster from an operational standpoint, the men involved showed great courage during the raid. In recognition of their tremendous bravery, three men—Scotsman Patrick Porteous and Canadians John Foote and Charles C. Merritt—received the Victoria Cross, the highest military honour bestowed by the Commonwealth. In a tragedy such as the Dieppe Raid, Merritt’s actions were indeed worthy of attention.

Charles C. Merritt was born in Vancouver on November 10, 1908. He graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada in 1925 and then joined the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada reserve regiment. Merritt served in various roles and was eventually promoted to major and sent to Britain in December 1939. In March 1942, he became the commanding officer of the South Saskatchewan Regiment, and he and his troops were sent to the Isle of Wight to train for Operation Jubilee.

At Dieppe

During the Dieppe Raid, the South Saskatchewan Regiment accompanied the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada on the Green Beach. Their goal was to cut off the German forces at Dieppe by capturing the Saint-Aubin airfield on the banks of the River Scie. However, unexpected events forced the landing ships toward the wrong side of the river, which greatly complicated the troop deployment. The men therefore had to make their way to the nearby village of Pourville and use the only bridge there to cross the river. To make matters worse, the element of surprise was lost when the Germans detected the attackers.

Machine gun fire immediately fell on the soldiers who had disembarked, and casualties quickly mounted. Completely immobilized by the fire, the men didn’t dare cross the point. Just then Merritt raised his helmet in the air and shouted, “Come on over! There’s nothing to worry about here!” before crossing the bridge with a group of his men. Merritt kept going with no fewer than four round trips to bring more and more inspired soldiers across with him. Merritt’s actions were not without impact: after crossing the river, the Allied soldiers secured the village for a time before the German reinforcements arrived. At this point, however, the raid was already lost. The men had no choice but to retreat to the beach to get back to their ships, something Merritt and his men were unfortunately not able to do.

After the failed operation, they were captured by German soldiers and transferred to the Oflag VII-B POW camp. Merritt spoke very little about this period of his life, stating that “My war lasted six hours. There are plenty of Canadians who went all the way from the landings in Sicily to the very end.” Merritt attempted to escape with 64 other prisoners in early June 1943, but he was recaptured by German guards shortly thereafter. He was only released at the end of the war.

His post-Dieppe career

On October 2, 1942, while Merritt was still imprisoned, the media announced that he would receive a Victoria Cross for his actions in Pourville. The medal was officially given to him in person years later upon his release.

Merritt returned to the greater Vancouver area and was elected as a member of parliament for the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada from 1945 to 1949. After resuming his law career, Merritt stayed involved in the Canadian Army as the commander of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada until 1954. He died on July 12, 2000, at the age of 91.

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- “1866 Lieutenant-colonel Charles Cecil Ingersoll Merritt, VC, ED“, Gouvernement du Québec/Government of Quebec.

- “Charles Cecil Merritt, VC“, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian encyclopedia.

- “Charles C. I. Merritt, Canadian War Hero, Dies at 91“, New York Times.

- “Charles Cecil Ingersoll Merritt“, Gouvernement du Québec/Government of Quebec.

- “Heroes of Dieppe Disaster – 3 Victoria Crosses in 9 Hours“, War History Online.