A veteran of the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, Richard Pierpoint led a very full life! After arriving in North America as a slave, Pierpoint went on to become a respected leader of the Black communities established in Canada.

The history of Black people in Canada has long been erased or ignored for many reasons. Whether as free people or, unfortunately, as slaves, many Black people contributed to life in North America from the start of the colonial era. While slaves such as Marie-Josèphe Angélique or Olivier Le Jeune and their tragic stories are becoming more familiar to Quebeckers, many others have long been ignored by the general public. A veteran of multiple colonial wars, Private Richard Pierpoint is one of these historical figures.

From slave to soldier to local leader of the Black community in Upper Canada, Richard Pierpoint (as he was called) led a full but largely forgotten life. While we have a general idea of what happened to him, large parts of his story have been lost to time. This short article will present what we do know about this man’s eventful journey.

Arrival in the United States

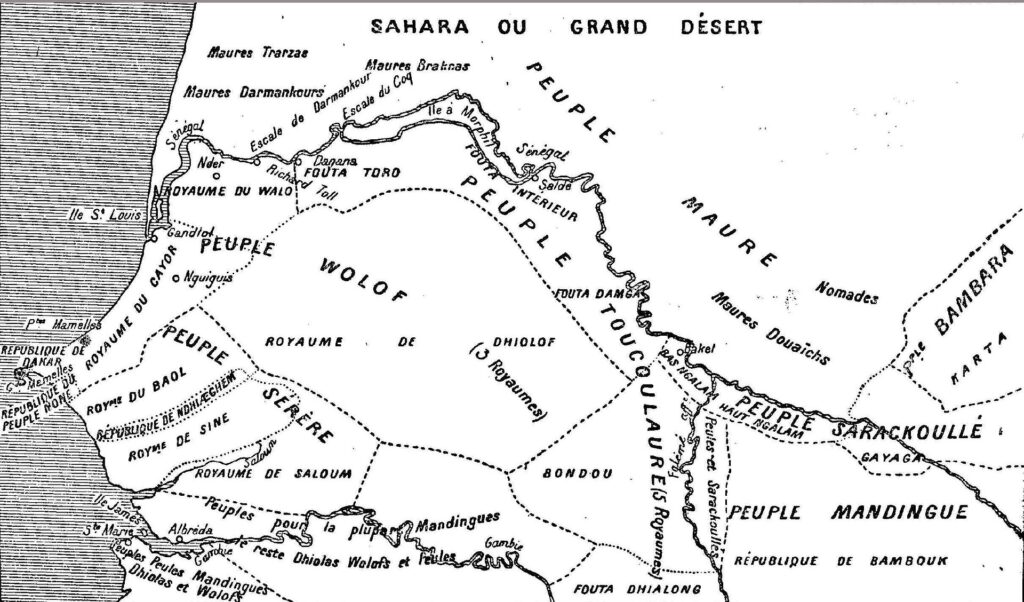

Very little is known about Richard Pierpoint’s life before he arrived in North America. Possibly born in 1744 in the state of Bundu (now part of Senegal), Richard Pierpoint seems to have been captured and enslaved at the age of 16. Historians David and Peter Meyler speculate that Pierpoint may have been captured as a soldier during a local military conflicts. He may also have been kidnapped by slave traders while travelling outside of Bundu.

Whichever the case, Pierpoint seems to have arrived in the United States as a slave in 1760, when he was sold to a British officer who gave him his family name, as was the custom of white slave owners. His life events are again hard to pin down after this time. Pierpoint may have been the personal assistant of this officer (or other slave owners) and may have travelled to a number of battlefields. After all, for many British officers, owning and taking a slave to the front lines was a sign of prestige and a testament to the owner’s wealth. However, Pierpoint probably found his freedom sometime during the American Revolution, although it is impossible to determine exactly how he did so.

In 1775, a number of British governors started freeing slaves who enlisted in the British army, and Pierpoint may have decided to do this as well. On the other hand, his owner may have enlisted with the Loyalist forces to fight the Americans and brought Pierpoint into military service with him. Pierpoint may also have run away from his owner and saw the army as a way to freedom.

We do know that in 1780 Pierpoint found himself in the Butler’s Rangers, a Loyalist military unit that operated between what is now the Canadian and American border and that carried out raids against American forces. The Butler’s Rangers earned a reputation for their very brutal tactics during raids and their ruthlessness in battle. Many free Black people also served with this mixed-race unit. Starting in 1780, Pierpoint and the rest of his unit were stationed in the Niagara region until 1784, when the American Revolutionary War ended. After being discharged, Pierpoint settled in this area.

Right: A Butler’s Rangers soldier in his green uniform. Richard Pierpoint may have worn a similar uniform.

Life in Canada

In return for his military service, Pierpoint received 200 acres of land, similar to what any other soldier would have received. Holding onto the land was another matter, and many soldiers sold their property. With no home base and nowhere to go, Pierpoint seems to have kept his land for some time. Legally, Pierpoint would have been forced to maintain his land, farm part of it, and build a wood cabin of a certain size on the property. For a man who had known nothing but war and slavery for most of his life, and who possibly bore the physical and psychological scars of these traumas, these hurdles would not have been easy to overcome. Possibly in response to these constraints, Pierpoint and 18 other signatories submitted a petition to the British authorities in 1794 requesting that Black people (some of whom Pierpoint fought with in the war) be allowed to join their land together to form a community away from White people – a strong indication of the daily discrimination they experienced. Although the petition was rejected, it showed how Pierpoint served as a leader for Black people in Canada.

Pierpoint sold his land at the turn of the 19th century but remained in the area. We do not know what he did during these years, but he may have lived with friends and worked for them until the War of 1812. As a follow-up to his 1794 petition, Pierpoint launched another request asking the British Army to create an all-Black unit, a petition that was once again refused. However, given the pressing need for men, the British army finally acquiesced and founded the Coloured Corps (or Company of Coloured Men) led by Captain Robert Runchey. At the age of 68, Pierpoint once again joined the army to fight the Americans.

As a reward for his military services, Pierpoint was given more land to farm in 1820. Now at an advanced age, the veteran no longer wanted to work the land. In 1821, he asked the government of Upper Canada for money to return to Africa instead of the 100 acres it granted to him. This request was also denied. After accepting his new plot of land, Pierpoint settled in Garafraxa with a former fellow soldier, a man named Deaf Moses. Pierpoint possibly spent the rest of his life on his land with his friend while continuing to travel to Niagara to visit his former comrades in arms. Although he could not return to Bundu, Pierpoint would have adopted the West African role of griot, a storyteller-historian who travels from place to place collecting local and family stories and sharing them.

A mystery we may never solve

Large parts Pierpoint’s life may never be revealed to us. While he undeniably played an important role in the Black communities in Canada, it is a pity that his major contributions have been ignored through the years. Pierpoint fought many battles, both on the battlefield and off, for greater racial equality, only some of which are remembered to this day.

Cover photo: An illustration of Richard Pierpoint by artist Malcolm Jones (source: Musée canadien de la guerre/Canadian War Museum).

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- “Richard Pierpoint National Historic Person (c. 1744–c. 1838)“, Gouvernement du Canada/Government of Canada.

- “Richard Pierpoint“, L’Encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “Richard Pierpoint, pionnier de l’histoire militaire et raciale du Canada“, Radio-Canada (in french).

A complete book has been written about the life of Richard Pierpoint according to the little information found about him. We recommend reading it if you are interested in learning more:

- David Meyler and Peter Meyler, A Stolen Life: Searching for Richard Pierpoint, Toronto, Natural Heritage Books, 1999, 141 p.

For a more academic approach:

- Amadou Ba, L’histoire oubliée de la contribution des esclaves et soldats noirs à l’édification du Canada (1604-1945), Éditions Afrikana, Montreal, 2019, 300 p. (in french).

- Gareth Newfield, “Upper Canada’s Black Defenders? Re-evaluating the War of 1812 Coloured Corps”, Canadian Military History, vol. 18, no. 3, 2009, pp 31-40.