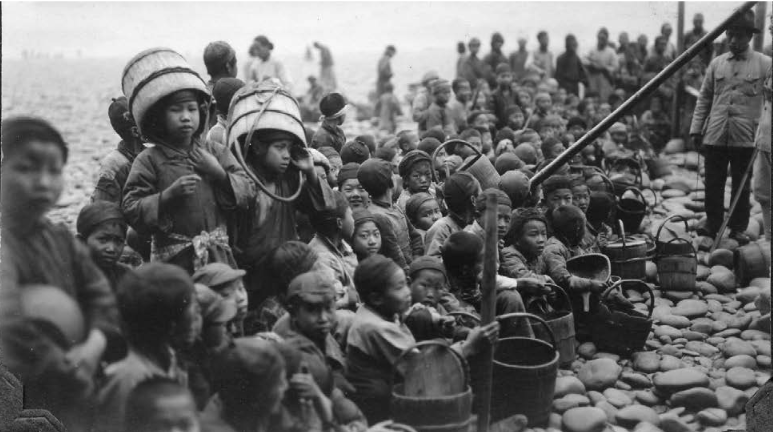

Many Canadian families went to China at the beginning of the 20th century to preach Christianity or to do business. However, with the outbreak of hostilities between Japan and China, these families also faced the horrors of war. Based in Chongqing, the capital of China held by the Guomindang forces, the Endicott family faced daily the Japanese bombs.

The oft-neglected question (despite years of war in Syria and other countries) of how civilians experience war has been a prominent topic since airstrikes against Ukrainian infrastructure began in February 2022. Canadians do not have a shared experience of bombings on their own soil, as the British did with the Blitz in England. However, Canadians travelled the world during the first half of the 20th century and recorded what it was like to live under the constant threat of wartime bombing.

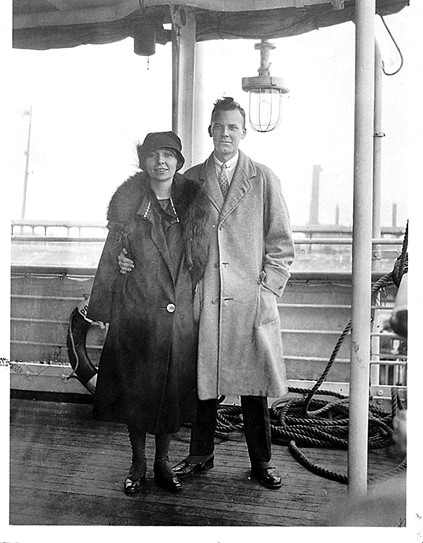

The Endicott Family

While living in China from 1925 to 1947 (with regular trips back and forth to Canada), the Endicott family lived in Sichuan province, where James Endicott worked as a missionary, teacher and advisor for the Chinese government. Correspondence from his wife, Mary Endicott, with her family in Canada reveals a fairly typical portrait of a middle-class woman in China who, with the help of two Chinese servants, cared for her three children and two young Chinese boarders.

Unlike her husband, who was constantly on the move, Mary Endicott’s life from 1939 to 1941 was marked by the constant fear for her family’s safety as Japanese bombers battered the cities of Free China.

Anticipating and experiencing the bombardment

Writing outside the new wartime capital of Chongqing, Mary Endicott explained that a bomb shelter was built starting in October 1937 when the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out. After months of waiting, Mary wrote “it’s come at last” to her sister in February 1938. Mary noted the anticlimax of this non-event, as she only learned of the bombardment several hours after it finished. This situation changed in January 1939, when Mary told her father that they had experienced “the heaviest bombing today that we have had yet.” The Endicotts could hear anti-aircraft guns, machine guns, and Japanese planes diving to unload their projectiles. When the bombs fell in the distance, the house would tremor and three unlocked windows would open with a crash. Even in the shelter, everything seemed to shake.

Despite the anxiety caused by the bombings, the people of Free China had to normalize these events to cope with the experience and psychologically survive the onslaught. During one attack, the Endicott family “went down to the dugout once and heard heavy planes zooming around and then go away, so we came up and started dinner. We had our soup and were just beginning the main course, when we heard them again, so we each took a plate in our hands and went back to the dugout.” The violence therefore increasingly became part of the social life of Free China’s inhabitants. In September 1939, Mary noticed how her family had become inured to the raids, which then had started to come at night. Over time, the bombings became part of the daily life of Chongqing residents, who organized their routines around the sirens and learned to sleep during the raids.

The bombings also had a profound cultural impact. For example, in private shelters, such as the one belonging to the Endicott family, people engaged in all sorts of activities such as singing and playing games to pass the time. In a play probably written by Mary Endicott for her children, the central theme is waiting for a bombing and the routine of the attack. The play begins with a discussion between the children about whether an air-raid siren will go off. The teacher repeatedly downplays their fears and insists that the children get down to work. When the siren finally goes off, the teacher keeps teaching her class, noting that they have an hour before the bombers come! As the students’ anxiety grows, she calms them by reminding them that this is not their first raid. Once in the shelter, the children tell stories to pass the time and assuage their anxiety during the attack.

Deadly raids of May 3 and 4, 1939

Although the bombings became “ordinary,” some attacks, such as the deadly raids of May 3 and 4, 1939, were extremely violent. During these two days, the air-raid sirens sounded continuously as planes constantly flew over Sichuan. With each siren, the children asked to go to the shelters, but Mary kept up their usual activities. Contrary to their habits, the Japanese bombers returned at about 5:00 p.m., surprising the family, who took refuge in their shelter before hearing the bombers drop their terrifying cargo onto Chongqing. Once everything went quiet, Mary and her children went outside and saw “great leaping flames coming from the city.” As they climbed a hill, they saw that five sections of the city were burning.

When they returned home, the family was worried: James had gone to the city the day before to help fight the fires caused by the previous raids. To fill the silence, Mary played music and sang hymns that praised the beauty and joy of life. James finally arrived home late at night. In a letter to his sister-in-law, he described this bombing:

“Then your ears pick up the rising inflection of the threatening hum of the approaching bombers. They seem to be getting angrier and angrier […] Suddenly you hold your breath as you hear the whistle and swish of falling missile [sic], followed by a sickening thud. There is a terrible cracking and splintering of falling houses and the windows and doors of the houses immediately above your head and the wall seem to rock as in an earthquake.“

In the same letter, he painted a visceral portrait of the brutality of these raids by describing a 20-year-old woman with mutilated legs and arms, a young married woman who kept holding her baby killed by shrapnel that pierced her own arm, and the screaming of victims trapped in the burning debris.

Inflation: another threat to survival

In addition to this military pressure, inflation was another part of war experienced by Canadian women. As mentioned above, the Endicott family was middle class by Western standards but financially well-off compared to the majority of the Chinese. Their standard of living was similar to that of a family of a modest Chinese civil servant living relatively well during the first years of the war thanks to a constant inflow of money but who was hit hard by inflation starting in 1939-1940. Like many Chinese families living on fixed wages or savings, the Endicotts were forced to sell many of their belongings before leaving China in 1941 due to this economic pressure.

The price of rice, a staple in the Chinese diet, traces the story of this terrible ordeal. In a letter written to her father in November 1940, Mary Endicott described her family’s economic woes:

“The war has at last touched us close in that respect. Within the last three months the cost of living has shot up to unheard of heights. The basis on which it is reckoned is the price of rice which in Chengdu rose to six dollars a bushel in June (pre-war was less than two dollars) but during the summer it began to soar and it has been doing so by leaps and bounds until last week it reached an all-high of 26. In some other places, such as Jenshow, where the Canadian School has evacuated, it has gone over $30 […]. Until this fall, we did not suffer from what amounts to inflation, because the gold exchange was in advance of it, but now that [sic] prices have gone up ten times pre-war and exchange is only 5 time pre-war. It is just the same result as if salary had been suddenly cut in half.“

Mary’s mention of the gold exchange is very important because only Westerners and the Chinese elite could benefit from this initial advantage. The pressure became so great for the Endicott family that they left China in 1941. However, James Endicott returned to the area from 1944 to 1947 as part of the war effort.

A different experience of war

For many people, the study of the past consists of collecting dates and facts in a strange and somewhat obsessive quest for information. However, for many historians, the goal is less about accumulating facts than reconstructing past experiences. In other words, the ultimate purpose of history is to build empathy for the present by looking back to build the future. The Endicott family’s experience gives us a window into an age of extremes that help us imagine a world where hope stays alive, even when the bombs rain down…

Article written by Daniel Lemire, PhD candidate in history at the Université du Québec à Montréal, for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- “Entre la guerre et la révolution : le projet de modernité nationaliste durant la décennie de Chongqing (1937-1947)“, Archipel UQAM.

- “Families with a proud legacy in China“, China Daily.

- “The Endicott Story in China“, The Virtual Museum of Asian Canadian Cultural Heritage.

To learn more about the presence of Canadian families in China in the early 20th century, the virtual exhibition Vic in China is available free online and has a page about the Endicotts. This page also contains a long article on the history of the Endicott family, available here.