The Tragedy of the Llandovery Castle

Canada had five hospital ships in WWI. Named after a Welsh castle, the hospital ship HMHS (His Majesty’s Hospital Ship) Llandovery Castle was used at sea to treat and transport men between Europe and Canada. Illuminated red crosses were visible on deck to indicate that the ship was being used for medical purposes and not for battle. The ship could thus be seen at sea, even at night, thereby safeguarding its mission as a hospital ship against possible attacks at sea.

Because the soldiers aboard hospital ships were no longer able to fight, and because the ships were staffed by non-combatant doctors and nurses, the international community agreed that the ships should be protected from attack (Geneva Convention: Hague X). The Geneva Conventions state that hospital ships can be boarded and inspected by enemy naval crews to make sure they are indeed hospital ships, but they are not to be the targets of military attack.

June 27, 1918

In June of 1918, 600 wounded men were to be transported from Liverpool, England, to Halifax, Canada, aboard the Llandovery Castle. There were also 260 crew members on board (ship crew, doctors, nurses and orderlies of the Canadian Army Medical Corps).

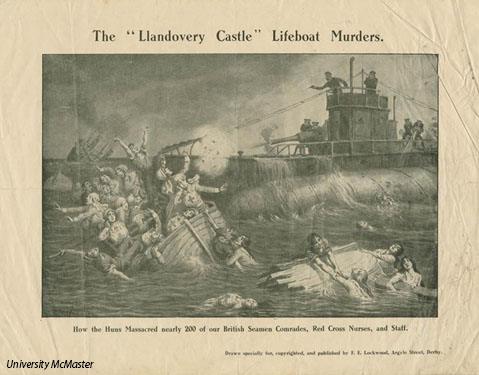

On the return trip to Liverpool on the night of June 27, 1918, the boat was intercepted by German submarine U-86 (in German Unterseeboot, often abbreviated to U-Boat. They were numbered sequentially during their production). The German submarine attacked the Llandovery Castle ship using torpedoes 116 miles southwest of Fastnet, Ireland (see the red dot on the map). The torpedoes hit the engine room and disabled the ship’s radio. This prevented Captain A. R. Sylvester from making a distress call and he immediately ordered the ship to be abandoned. The Llandovery Castle sank in less than ten minutes. Many of the crew and medical staff aboard who survived the initial torpedo blast were able to escape into lifeboats before the ship sank. However, the wreckage created a whirlpool which eventually drowned the occupants of all but three to five lifeboats.

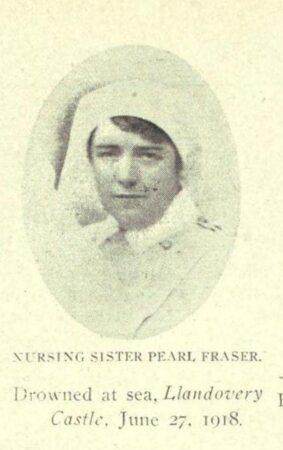

Picture of Matron Margaret Marjory (Pearl) Fraser, daughter of Lt. Governor of Nova Scotia, Duncan Cameron Fraser

“Unflinchingly and calmly, as steady and collected as if on parade, without a complaint or a single sign of emotion, our fourteen devoted nursing sisters faced the terrible ordeal of certain death – only a matter of minutes – as our lifeboat neared that mad whirlpool of waters where all human power was helpless. I estimate we were together in the boat about eight minutes. In that whole time, I did not hear a complaint or murmur from one of the sisters. There was not a cry for help or any outward evidence of fear. In the entire time I overheard only one remark when the matron, Nursing Matron Margaret Marjory Fraser, turned to me as we drifted helplessly towards the stern of the ship and asked:

“Sergeant, do you think there is any hope for us?”

“I replied, ‘No’, seeing myself our helplessness without oars and the sinking condition of the stern of the ship.

A few seconds later we were drawn into the whirlpool of the submerged afterdeck, and the last I saw of the nursing sisters was as they were thrown over the side of the boat. All were wearing lifebelts, and of the fourteen two were in their nightdress, the others in uniform. It was doubtful if any of them came to the surface again, although I myself sank and came up three times, finally clinging to a piece of wreckage and being eventually picked up by the captain’s boat.”

– Sergeant Arthur Knight (The Great War Documents)

Murder at Sea

After the sinking of the Llandovery Castle, at least three lifeboats with passengers remained afloat. One of the lifeboats contained the captain of the sunken ship. As this lifeboat attempted to pick up swimming survivors, or those floating on bits of debris, a member of U-86 ordered the captain’s lifeboat to come alongside the German submarine. When the lifeboat did not immediately comply with this request, a warning shot was fired. A submariner on the U-Boat ordered Captain Sylvester on board and accused him of carrying American airmen on the Llandovery Castle. If true, this would have been a breach of the rules of war. The Captain denied this charge and told the Germans that he had only been carrying Canadian medical personnel. Another survivor from the lifeboat, a doctor named Major T. Lyon, was also brought on board, and questioned. He denied being an American airman and refuted the charge that the Llandovery had been carrying munitions. Sylvester and Lyon returned to the lifeboat, but the U-Boat did not leave.

After circling for a time, two more officers of the Llandovery Castle were ordered aboard U-86. The Germans saw an explosion when the ship was hit; for them, this was proof that there must have been ammunition on board. The interrogated officers from the Llandovery disagreed, stating that any explosion was the result of the ship’s boilers exploding due to the torpedo. These officers also returned to the lifeboat, but still the U-Boat did not leave.

A short time later, as the Captain’s lifeboat drifted away, its occupants heard shots fired from the 8.8 cm stern gun mounted on the U-Boat. Two shells passed overhead. Another twelve or so shots were fired at the other surviving lifeboats.

Deaths at Sea

Approximately 36 hours after the sinking, the 24 occupants of the Captain’s lifeboat, the only survivors of the hospital ship Llandovery Castle, were rescued by the English destroyer Lysander. A total of 234 doctors, members of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, soldiers and seamen died in the sinking of the ship and machine-gunning of the lifeboats, including 14 nurses.

Missing from the photo: Jean Templeman and Gladys Irene Sare

War Crimes

There are internationally agreed upon rules of war. These rules, laid out in documents like the Geneva and Hague Conventions, set out expectations of conduct during violent conflict, and are intended to prevent the worst horrors of war.

U-86 violated these rules, both in sinking the Llandovery Castle and in shooting the survivors in lifeboats. First-Lieutenant Helmut Patzig, captain of the German submarine, did not record the sinking in the U-Boat’s logbook; the latter indicated rather that the submarine was far from the place where the sinking of the Llandovery Castle occurred. Patzig also instructed his crew to never talk about the incident. In spite of this law of silence, the shipwreck quickly became public knowledge, notably thanks to the testimonies of the 24 survivors. The killing of Canadian nursing sisters infuriated people, with Allied leaders publicly condemning the German actions.

After the end of the conflict, three German officers, including Patzig, were accused of war crimes: the commander, however, fled before his trial. As for the two other officers, they were found guilty, even though they had followed their captain’s orders. This trial set a precedent in war crime tribunals. At the Nuremberg trials, after WWII, similar defences where German officers claimed to have merely been following orders were dismissed. The tragedy of the Llandovery Castle was used as an example for world militaries, showing that it was illegal to carry out illegal orders (in this case, it was illegal for the officers to obey the captain’s orders to attack a hospital, because attacking a hospital is illegal).

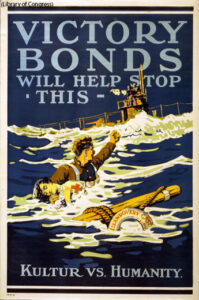

The strongest reaction was in Canada. The government even used this tragedy for propaganda purposes, particularly to promote the sale of war bonds. Also known as “victory bonds”, these bonds were a way for governments to borrow money from their citizens, usually by appealing to their desire to help win the war. These loans were repaid with interest after a set period of time.

Halifax Memorial

Nursing casualties are listed on this memorial, located in Point Pleasant Park, Halifax, Nova Scotia

(Creative Commons)