During the Second World War, the First Nations’ position on enlistment was rather mixed. While some felt that the war was a white man’s war, and thus of no concern to them, others felt that enlisting in the war was a way to gain opportunities for themselves and their people, and to further the cause of Indigenous rights. Despite this willingness to get involved, policies within Canada’s various defense organizations were not geared towards welcoming non-white men. The majority of Indigenous soldiers were channeled into the Canadian Army, but refused entry into the Navy or the Air Force. These two organizations only accepted people of white ancestry until 1942-1943. An estimated 8 500 soldiers of Indigenous origin joined the armed forces during the Second World War.

Among those who enlisted, a small group of individuals from various Canadian First Nations were redirected on arrival in England to join a secret mission in London. The Cree community was quickly targeted, as the majority of them spoke both English and one of the 5 branches (dialects) of the Cree language, commonly known as Nehiyaw Win. These men were assigned to one of the most important missions of the conflict.

Recruited for their bilingualism, these men became code-transmitters for the Allied army. As the Axis forces had no knowledge of the native languages of North America, the use of these dialects to communicate ensured total impermeability. It’s also important to mention that Indigenous languages were losing significant numbers of speakers due to the residential school system and the oppressive colonial policies implemented across Canada in the first half of the 20th century. As a result, communicating information on attacks, movements and strategies in these languages made them impossible to decode for enemy forces, giving the Allies a robust advantage.

The process was quite simple. A Cree transmitter would translate the information from English into Cree before passing it on to the other station, where another Cree transmitter would translate it back into English. These messages contained a variety of vital information, including the number of Mustang aircraft (called pakwatastim meaning wild horses) or Spitfire aircraft (called iskotew meaning fire). These exact terms didn’t exist in the Cree language, so the translators had to repurpose existing words.

The Cree weren’t the only Indigenous soldiers selected to work as coders. The Ojibwe, Navajo and Comanche nations were also sought out and employed in coding work. In the United States, Navajo involvement in code talking is well known and widely documented in public history. In Canada, Cree involvement is much less well known, as these men were sworn to secrecy regarding their work as code talkers. In 1963, the Canadian government officially recognized the Cree coding operation when documents were declassified. However, it was only recently, following the testimony of relatives of soldier Charles Tomkins, that the Canadian public really began to discover the importance of these men’s involvement as coders within the armed forces during the Second World War.

Charles Tomkins

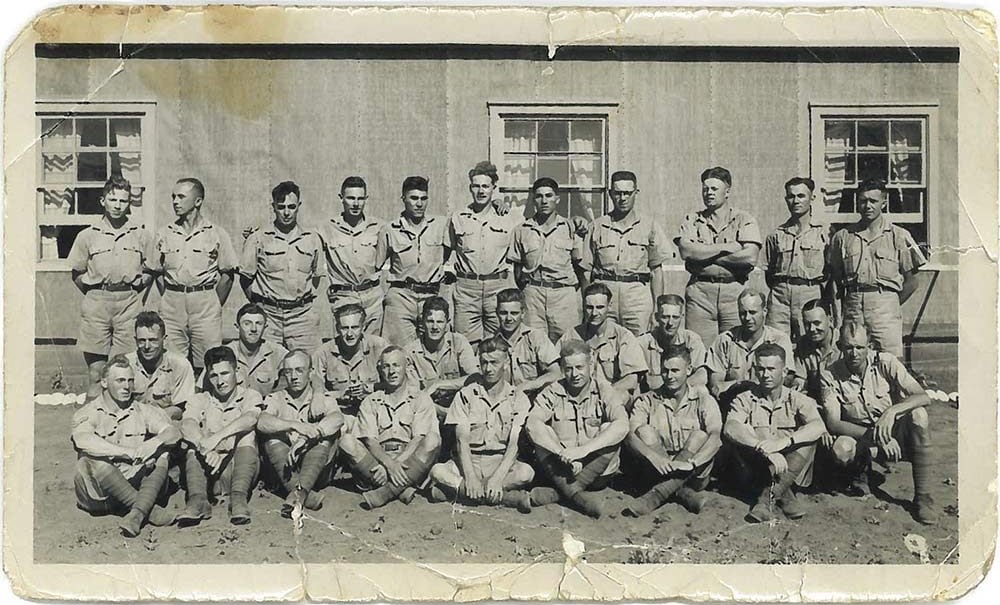

Charles Tomkins’ story recently came to the fore thanks to the production of a mini documentary recounting his exploits (Cree Code Talker by Alex Lazarowich). A Métis from Alberta, Charles « Checkers » Tomkins was a veteran of the Second World War. After arriving in Britain, he joined the 2nd Canadian Armored Brigade. Shortly thereafter, he received a secret summons from the Canadian High Command in London. Numerous Indigenous men from various nations were summoned to the meeting. Tomkins was paired up with another Cree and trained as a translator. He was then trained by the Canadian army to become a code transmitter. Following his training, he joined the US 8th Air Force as a code talker. He was stationed in England, France, Germany, and Holland (Netherlands). His role as a code transmitter was not revealed to his family until much later. Only one of Charles Tomkins’ brothers knew of his role during his lifetime. The rest of the family only discovered what he had done in the war following his death in 2003.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, the benefits that Indigenous soldiers thought they would gain from involvement in the army and the war effort were never realized. In the years following the war, conditions for First Nations Canadians did not significantly improve, and many veterans felt abandoned by the country they had fought for.

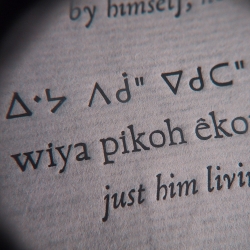

Photo de couverture : A text in the process of being translated (source: Ferrous Büller/Flcrk).

Article rédigé par Aglaé Pinsonnault pour Je Me Souviens.

- « Charles Tomkins« , L’Encyclopédie Canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- « Cree Code Talkers« , L’Encyclopédie Canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- « Cree Code Talkers« , Histoire Canada/Canada’s History.

The short documentary Cree Code Talker directed by director Alex Lazarowich in 2016 is also available for free via the National Screen Institute website. And finally, for a text with a more academic approach:

- William Meadows, « Honoring Native American Code Talkers: The Road to the Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-420)« , American Indian Culture and Research Journal, vol. 35, no. 3, 2011, pp. 3-36.