On 7 November 2017, the Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, made an official apology for the Jewish refugees who had been refused entry to Canada a few months before the outbreak of the Second World War. This article, written by historian Rosalie Racine, looks at the particular Canadian Jewish situation, and the role of anti-Semitism, in the context of the rise of Nazism and during the Second World War.

When we think of the 1930s and 1940s, we immediately hearken back to the events of geopolitical strife in Europe. However, Canada also went through turbulent times in that era. For example, the country saw a rise in anti-Jewish sentiment after the 1929 economic crash. To explain how this anti-Semitism grew, this article looks at the immigration of Jews to Canada, their internment in the east part of the country, and the rise of Nazism in Canada.

Jewish immigration to Canada

Canada’s immigration policy has always been racially selective and economically selfish. The situation in the early 1930s and the dire impacts of the economic crisis further reduced opportunities for people to immigrate here. The government’s immigration policy focused on the single goal of keeping Canadian unity intact. William Lyon Mackenzie King, the Canadian Prime Minister at the time, knew that letting Jewish refugees settle in Canada would jeopardize his future re-election. In fact, his government’s policy was based on the fear of a backlash against Jewish immigration given the significant anti-Semitism shared by many Canadians at the time. Jews were therefore restricted to just a few areas in the country with a cap on their numbers. For example, the government asked the Canadian National Land Settlement Association (a division of CN) not to accept Jewish farmers as they did not believe they were actually farmers and thought they would instead move to the city, where unemployment remained high.

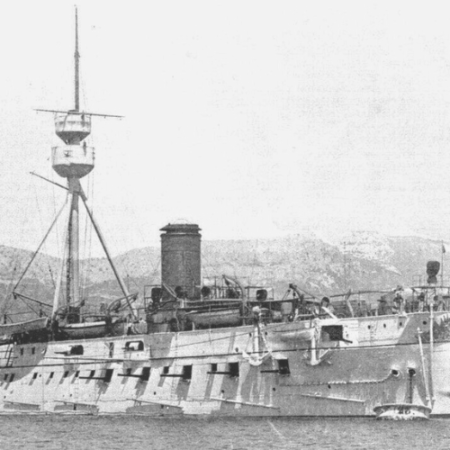

The Jewish immigration experience was also impacted by the situation in Germany. When Hitler rose to power, Canada did nothing out of a desire to steer clear of Europe’s problems. In 1940, or soon after the Second World War broke out, the UK began discussions with Canada, asking it to take foreign internees, prisoners of war, and evacuated children. The United Kingdom first asked Canada to take 9,000 German “enemy aliens” and prisoners of war, which the Canadian government rejected outright.

The best-known example of how hard it was for Jews to immigrate to Canada was when, in 1939, the MS Saint-Louis luxury liner carried 907 German Jews trying to escape Nazi persecution. The passengers were turned away from Cuba, some South American countries, and the United States, before they headed for Halifax, where they were again refused entry. In the end, the ship returned to Europe.

Internment camps

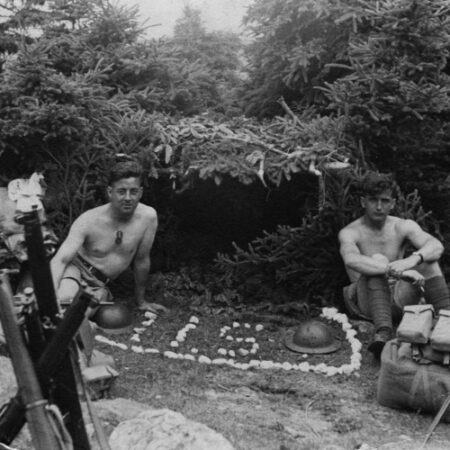

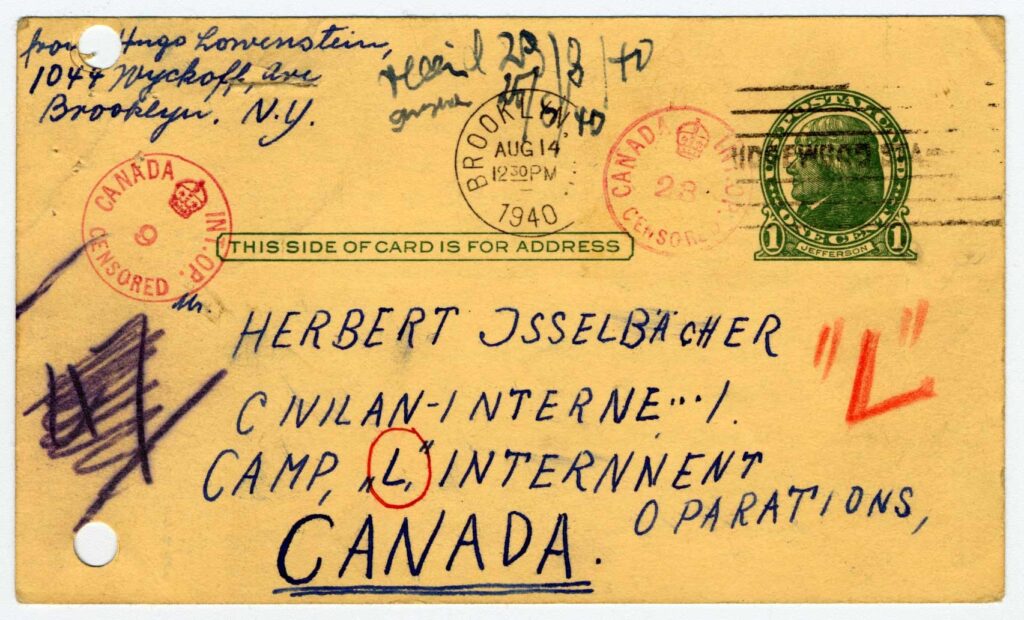

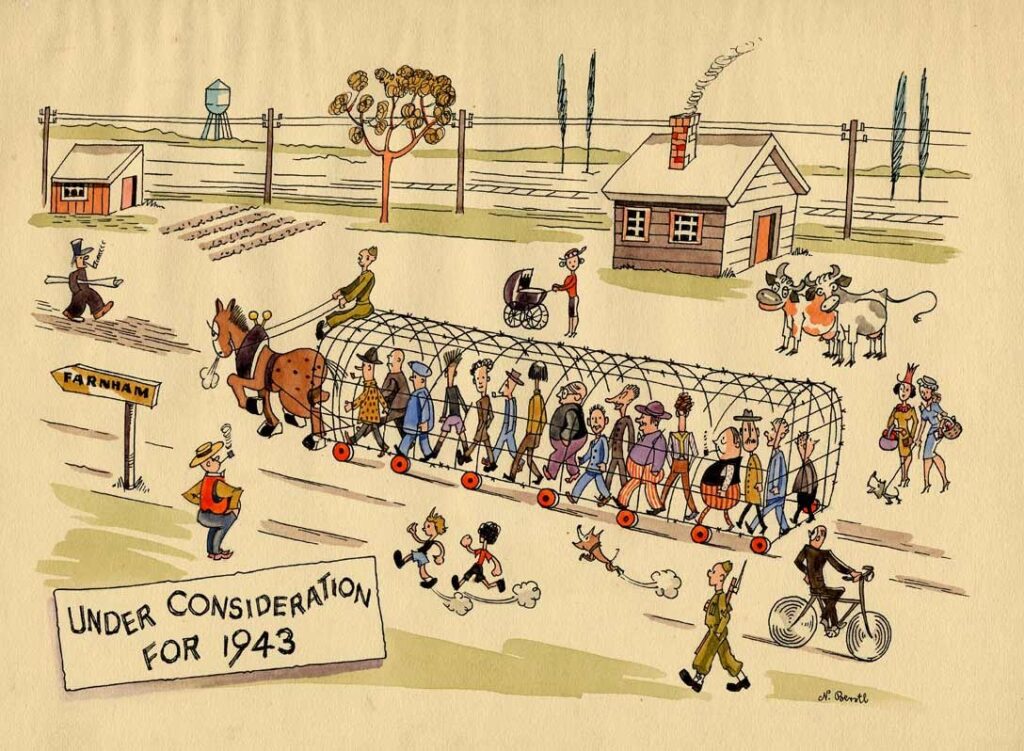

Jewish refugees who did manage to come to Canada were sent to different camps in the east. Even when in a friendly country, internment was a traumatic experience for the Jewish refugees, as many had experienced the Nazi concentration camps and felt that their allies betrayed them by putting them in camps as well.

However, the Canadian internment camps did seem like normal daily urban life, with their schools, cafés and places of worship. Canadian Jewish organizations and charitable groups provided the internees with what they needed to maintain this illusion of normal life. Sports and the arts also played an important role in their daily lives.

Surprisingly, internment had positives for some refugees, as those wanting to settle in North America after the war could learn and perfect their English. The camp also set up schools that provided academic, religious and technical education to the prisoners and refugees. The camp in Sherbrooke alone ran seven different educational programs. Internees at the Île-Sainte-Hélène camp were eventually allowed to write the McGill University entrance exams so that they could go to university after being released.

However, life was much harder at other camps in Canada. Many refugees were sent to the Red Rock camp in Ontario, about fifty of whom identified as Jews. This camp was also mainly used as a detention centre for pro-Nazi Germans. There, many of the Canadian guards, who were veterans of the First World War but were denied active service for the Second World War, offered rewards and money to inmates who would make or get them Nazi insignias or symbols. A small workshop was set up at the camp that took orders for Nazi swastikas. The Nazis also played practical jokes on the Jewish internees. For example, when the Jews were allowed to eat kosher on Yom Kippur, some Nazis working in the kitchens replaced the food with fried pork.

The rise of Canadian Nazism

Nazis sympathizers were not only at the Canadian internment camps. In fact, the Nazi movement in Canada, which German organizations like the Deutscher Bund Canada (German Alliance of Canada) helped set up, gained momentum through pro-Hitler clubs, subscriptions to German literature, or publicity for Nazi events in Germany. The Nazi Party’s involvement in Canada is difficult to fully pin down, as German aid rarely came in monetary form, which significantly limited the support provided. However, as propaganda was a major weakness of the Deutscher Bund Canada, the Nazi government provided much-needed assistance to bolster the success of their movement.

But while English Canada had its own pro-Nazi factions, nowhere was this movement stronger than in Quebec. The interwar period in Quebec was marked by a revival of French-Canadian nationalism due in part to the economic crisis. The fascist anti-Semitic movement in Quebec was organized around the personality and ideas of Adrien Arcand, whose ideology and “blue shirt” militants were inspired in part by the anti-democratic and racist ultranationalism of Lionel Groulx that advocated for stripping Jews of their civil and political rights. Arcand’s blue shirts wanted to help Quebec rise out of the economic crisis that was raging around the world. As part of the National Social Christian Party, Arcand’s blue shirts reached a wide public audience through a range of publications, and their news was carried in mass-circulation newspapers such as Le Devoir and La Presse.

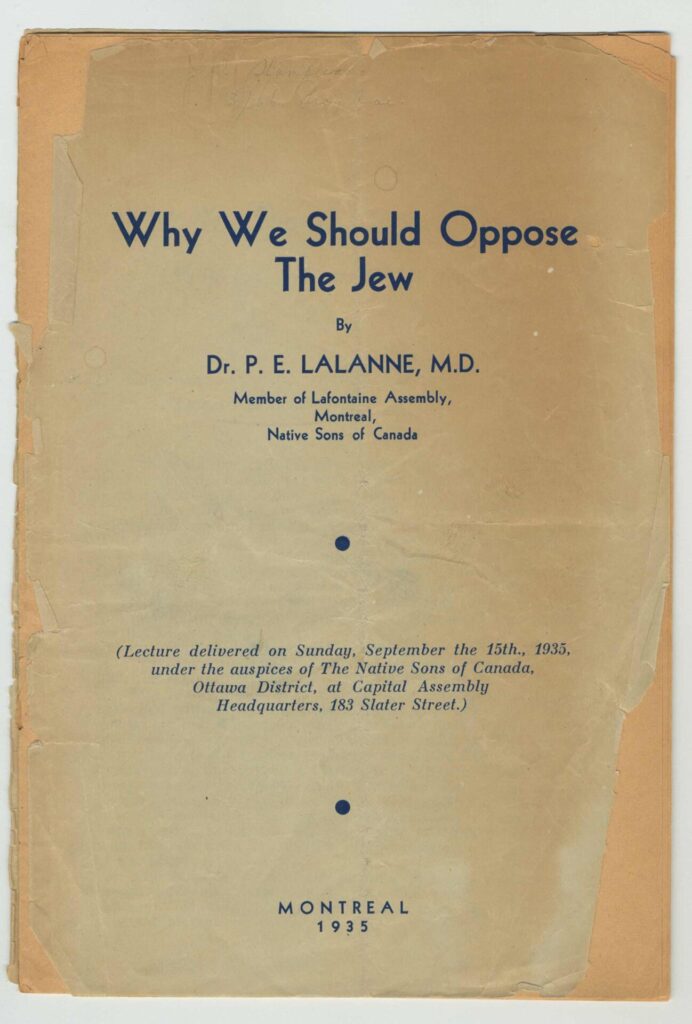

À droite : An anti-Semitic propaganda essay written by Dr. Lalanne, a member of the Native Sons of Canada, based on a lecture delivered on September 15, 1935 under the auspices of the Native Sons of Canada.

Ongoing trials and tribulations

For the Jewish refugees, Canada was just a dot on the map and a country whose doors were closed and would always be closed. When Auschwitz became an extermination camp, the warehouses used to store the Jews’ stolen possessions were called “Canada,” or a place of great abundance that was off-limits and closely guarded[1].

[1] As quoted in Erna Paris’s Jews, An Account of Their Experience in Canada (1980), p. 58.

Cover photo: Adrien Arcand, leader of the National Unity Party, gives a speech during a rally at the Paul-Sauvé Center in 1965 (BAnQ archives).

Article written by Rosalie Racine, PhD candidate in history at the Université de Montréal, for Je Me Souviens. Our warmest thanks to the Montreal Holocaust Museum for the images! Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- “Camp History & Information“, New Brunswick Internment Camp Museum.

- “Internment in Canada“, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “Réfugiés juifs de 1939 : des excuses officielles de Trudeau le 7 novembre“, Radio-Canada (in french).

For a more academic approach, we recommend the following books:

- Irving Abella & Harold Troper, None is too many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933–1948, Toronto, Key Porter, 2000, 340 p.

- Jean-François Nadeau, Adrien Arcand, führer canadien, Montréal, Lux, 2010, 408 p. (in french).

- Jonathan F. Wagner, Brothers Beyond the Sea: National Socialism in Canada, Waterloo, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, [2012] 1981, 190 p.

- Ernest Robert Zimmermann, The Little Third Reich on Lake Superior: A History of Canadian Internment Camp R, Edmonton, University of Alberta Press, 2016, 346 p.

In addition, on October 22, 2022, Rosalie Racine was on Histoire de passer le temps to present the various forms of anti-Semitism in Canada during the war. To listen to her segment, in french, click here! With the participation of Chloé Poitras-Raymond as host, Cathie-Anne Dupuis and Eliott Boulate as guests and Clément Broche as sound engineer.