Clarence David Lapierre was one of the first soldiers to land in France during the Second World War as a paratrooper with the 1st Canadian Battalion. However, many people are still unaware of the role that Canadian paratroopers played in the war’s largest landing assault.

The Normandy landings on June 6, 1944, were a frank success thanks to the combined efforts of all contingents of the Canadian Army and its allies. The work of Canada’s infantry and naval forces entered our collective memory thanks to photos. However, the significant contributions of Canadian paratroopers were not captured to the same degree.

Yet, hundreds of Canadians volunteered for the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. For example, Clarence David Lapierre, or “Dude” as he was called by his fellow soldiers, was one of these young enlistees. Lapierre was born on November 9, 1923, in Owen Sound, Ontario, which is best known as the birthplace of the famous pilot Billy Bishop. During the First World War, Bishop shot down 72 enemy aircraft and even survived a dogfight with Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the “Red Baron.”

After the war, Bishop spent a long time recruiting troops for the Royal Canadian Air Force. However, we can never be certain that Bishop’s exploits or recruitment efforts had any influence on Lapierre’s decision to enlist, as we know very little about Lapierre’s pre-war life. While Bishop’s and Lapierre’s life paths were very different, they both decided to take to the skies once they heard the call of war.

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion

Canada had no paratrooper units before the Second World War. After all, airplanes were still a relatively recent invention at the time. For most people, the idea of jumping off one seemed quite foolhardy indeed! While many European countries ran paratrooper testing during the interwar period, Nazi Germany was the first to get a real program off the ground. The Fallschirmjäger, or the Luftwaffe’s airborne division, saw success in the early stages of the war and showed the Allies how useful these units could be.

Yet, this usefulness did not get Canada fully on board right away. While Great Britain and the United States launched their airborne programs at the onset of the war, the Canadian government was more hesitant to follow suit for reasons as diverse as they were nebulous, as explained by military historian Bernd Horn. E.L.M. “Tommy” Burns was the officer who pushed hard to create a paratrooper unit after German troops demonstrated their prowess in the air. Unlike many of his colleagues, Burns stayed on top of cutting-edge military practices and quickly saw the advantages of this type of unit for Canada.

From 1940 until the creation of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion in July 1942, Burns constantly lobbied the Canadian Army to raise the unit. He argued that paratroopers were the quickest way to deploy soldiers if ever the Germans invaded Canadian territory. This argument swayed the military, which recruited a first group of 26 officers and 590 soldiers for the unit.

When the first paratroopers were sent to the United States and Great Britain for training, their primary thought was indeed that they would be used for homeland defence. It was only in 1943, after Canadian paratroopers came under the command of British airborne operations, that they were deployed to fight in Europe.

Clarence Lapierre enlists

This was the backdrop for Clarence Lapierre’s debut as a paratrooper. He joined the Canadian infantry on January 21, 1943, and completed his basic training a few months later in his home province of Ontario. Like many members of the Canadian infantry, Lapierre was then sent to Great Britain for further training.

Although he was initially transferred to different infantry units, Lapierre’s goal was to become a paratrooper. For many young men, the paratrooper units were an exciting opportunity to leave Canada for adventure. The time that Lapierre spent with these paratroopers while he was in the UK could have been what influenced his decision to join the unit. The members of the 1st Battalion were thought of very highly, as Private Jeff B. Kelly explained:

“Then I heard about the paratroopers. They were the best. We heard about them and they were the tops in the army. They were the only outfit that I wanted to get into. I just wanted to parachute and I knew that they were the best.” (Gary C. Boegel, Boys of the Clouds, p. 8).

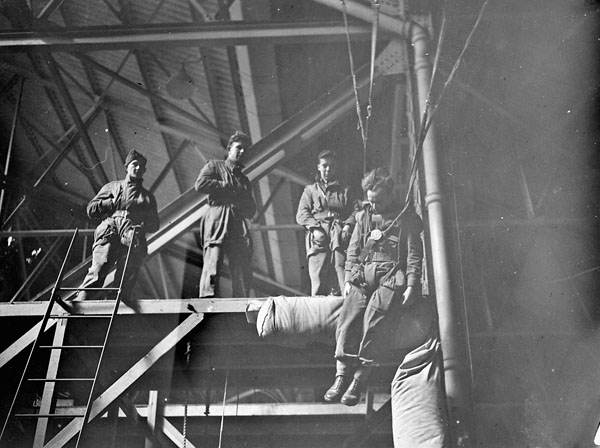

The paratroopers earned this reputation through very intense training. In his account of that time, Lieutenant Bill Jenkins, an Orderly Officer with the unit, said that the recruits were selected primarily for their endurance. He recalled how they had 60 applicants for a unit that could only take 35 people, so his commanding officer had them run until 25 of them dropped out! That was just the beginning, as their training continued with a variety of Herculean tasks, from running to making multiple jumps, until the best of the best emerged.

While the physical prowess of the 1st Battalion added to their prestige, other factors did as well. For example, Sergeant Nelson N. MacDonald was inspired by the elegant figure cut by these men: “[…] I had witnessed a precision drill performance by a platoon of airborne soldiers and with the smartness, including the maroon beret and the highly polished jump boots, I was sold” (p. 3). MacDonald wasn’t the only one who was impressed by the look of the 1st Battalion. As Charles Eliott described:

“I felt that they were disciplined and had a great level of fitness. I liked the whole general make-up of the airborne soldier. There was a pride that he carried himself with. You never saw one with a cap stuck in his back pocket or his hands in his pockets. […] I guess that it was a combination of the maroon beret; the jump wings and the boots that made me want to join.” (Gary C. Boegel, ibid., p. 11).

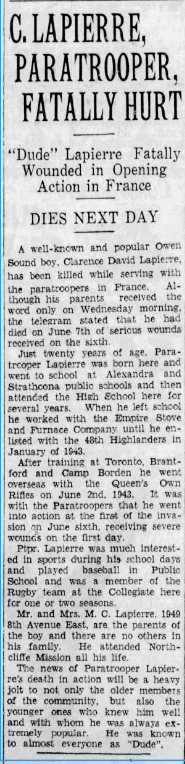

This positive reputation was probably what attracted the young, athletic and charismatic Lapierre to the paratrooper unit. According to a newspaper article, Lapierre was very physically fit. He played baseball and rugby as a teen and was frequently described as being very popular in his hometown. This was perhaps why he identified with paratrooper culture.

Lapierre joined the 1st Battalion on January 17, 1944, after volunteering for the war. Like other Canadian paratroopers, Lapierre did his basic training in Ringway, England, until March 3, 1944. He continued to hone his skills to get ready for the Normandy landings, which would be his first field operation.

Normandy awaits

The 1st Battalion set down in Normandy during the night of June 5 to 6, 1944. Its mission was to dismantle the German defences in preparation for the landings. The three companies had different orders: secure one point, destroy another, and disable as many enemy troops as possible!

The conditions for the jump that night were not ideal. While the clouds provided excellent cover, they also complicated the operation! On the ground, the soldiers became scattered right in the middle of the action and a number were hit by enemy fire.

This is how Lapierre lost his life. Available sources indicate that Lapierre deployed with Company B, whose goal was to destroy a bridge over the River Dives and prevent any German reinforcements from reaching their position. We do not know exactly when Lapierre was hit, but we do know that he landed east of the town of Caen. Lapierre did not die right away, as his parents were told that he succumbed to his wounds on June 7, 1944, which means that his comrades managed to recover him before he died.

Lapierre was one of the many paratrooper casualties from June 6: out of the 543 deployed in Normandy, 21 were killed and 94 were wounded. Despite these immense losses, the Battalion could at least find solace in the fact that their mission was a great success.

The Battalion after Lapierre

The Battalion’s success in Normandy convinced the Canadian Chief of the General Staff to continue deploying paratroopers in Europe, and these men continued to prove their worth in France and the Netherlands right up to the end of the war, after which the Battalion was disbanded.

There were a number of roadblocks to the Canadian paratrooper program during the Second World War, and the army took a long time to formally adopt the unit. Despite the great skills of its men and their wartime feats, the program was quickly consigned to obscurity: “We called ourselves the forgotten battalion,” said Lieutenant Ken Arril (Bernd Horn, p. 36). It was not until the late 1960s that Canada resumed its parachute program by hearkening back to the exploits of the 1st Battalion. Today, the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment is the only regular unit that specializes in paratrooper operations.

While Owen Sound can pride itself on being the birthplace of flying ace Billy Bishop, it should also remember the sacrifice of its other lesser-known citizens. Unfortunately, Lapierre’s story is not unusual, as thousands of other young people met a similar fate in Europe. Remembering our service people means remembering all those who left and who never came back.

Right: A newspaper article announcing Lapierre’s death in Normandy.

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- “1st Canadian Parachute Battalion“, Centre Juno Beach/Juno Beach Centre.

- “LaPierre, Clarence David“, Black Canadians Veterans Stories.

- “Private Clarence D Lapierre“, ParaData.

- “Private Clarence David Lapierre“, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion Virtual Museum.

- “Private Clarence David Lapierre“, Gouvernement du Canada/Government of Canada.

For a more academic approach:

- Gary C. Boegel, Boys of the Clouds: An Oral History of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, 1942-1945, Victoria, Trafford, 2005.

- Bernd Horn, ““A Question of Relevance”: The Establishment of a Canadian Parachute Capability, 1942–1945“, Canadian Military History, vol. 8, no. 4, 1999, pp. 27-38.

- Bernd Horn & Michel Wyczynski, Tip of the Spear: An Intimate Account of 1 Canadian Parachute Battalion, 1942-1945. A Pictorial History, Toronto, Dundurn Press, 2002.

This article was published as part of our exhibition on D-Day: When Daylight Comes. Visit our exhibition to learn more about the history of the Canadian who landed in Normandy!