Have you ever heard the old saying “an army marches on its stomach”? During the First World War, Canada produced millions of pounds of food that was sent to the warfront. But how did this impact Canadian Kitchens? Let’s take a look at some of the ways World War 1 impacted food for Canadians, both at home and abroad.

Changing Food Habits

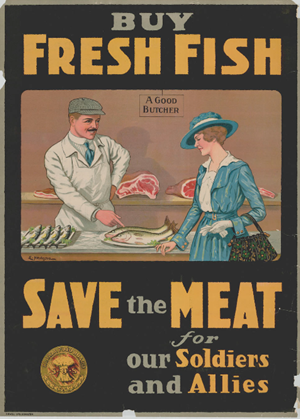

Beginning in 1914, The Government of Canada, as well as provincial governments across the country, pledged foodstuffs to the war effort. For example, Quebec sent 4 million pounds of cheese to Britain as part of their contribution. However, as the war raged on, the increasing need for supplies overseas often meant access to certain ingredients in Canadian kitchens was limited. Wheat prices increased, making it difficult for many families to afford it. In 1917, the Canadian government began to place regulations on the amount of food Canadian families could enjoy. To ensure soldiers fighting overseas had enough food, red meat, white flour and white sugar were all rationed as part of the war effort. As a way of reducing consumption of certain staple goods, the Canada Food Board started a campaign for Canadians to change their diets.

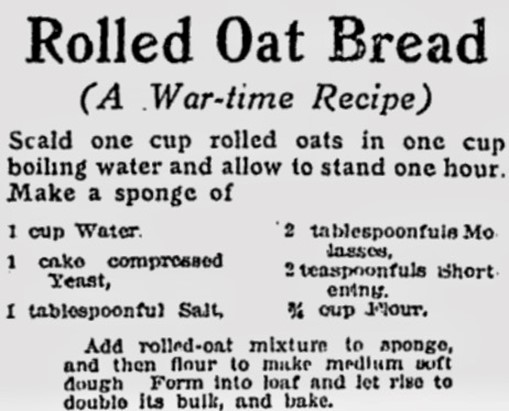

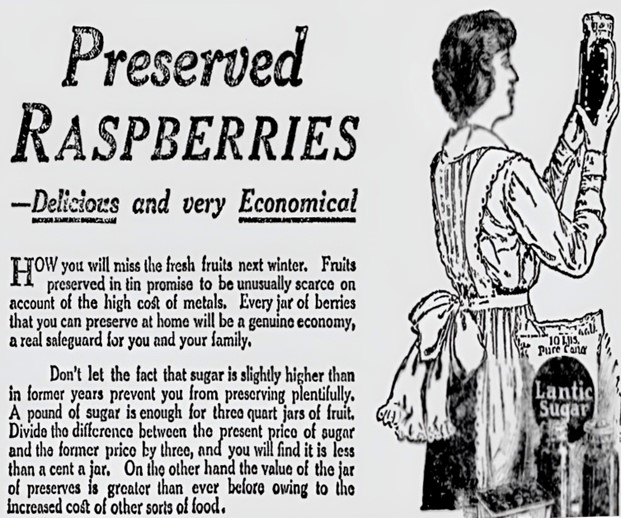

Eating certain products became unpatriotic and considered a detriment to the war effort. Other foods, such as fish and vegetables, grew in popularity as a result. “Meatless Fridays” became common place across the country. By 1918, using non-wheat flour was made mandatory. To help Canadians cook according to these changes, papers printed war menus and recipes that followed the new rationing guidelines of the Canadian government. The Canada Food Board also came out with a series of cookbooks that could be purchased for five cents each. One popular food in these menus was war bread. These recipes often replaced wheat flour for oatmeal or mashed potatoes. Other recipes asked the baker to use leftover bread or breadcrumbs to reduce waste.

Food economics (getting the most out of your ingredients and managing waste) became an important skill to learn for many in Canada. Quebec’s Department of Agriculture worked alongside the Écoles Ménagères Provinciales to create cooking classes for women across the province. These classes helped students learn how to reduce food waste. The school’s principal, Jeanne Anctil, as well as other teachers at the school, conducted weekly classes on cooking, and other household skills, to women across the province. Thousands of women came out to these courses during the war.

The local Council of Women in Montreal also created a Food Services Pledge, whereby women pledged to reduce their family’s food intake and waste during the war. War gardening also became a common practice to ensure that families had easy and cheap access to vegetables and herbs.

Right: Born in 1875 in Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière, Jeanne Anctil was the principal at the Écoles Ménagères Provinciales in Montreal. During the war, she, and other teachers at the school, gave lectures across Quebec to help families reduce their food waste.

Fundraising through Food

Cookbooks not only provided Canadians with new recipes to help conserve food, but they also provided a means to raise funds for the war effort. Various women’s groups, including the Imperial Daughters of the Empire, created and sold cookbooks to raise money. In Montreal, the ladies of the Westmount Soldiers’ Wives League published their cookbook in 1915. Simply titled, The Cook Book, the book’s cover design was created by Montreal Star cartoonist Arthur G. Racey. Proceeds from The Cook Book funded the league’s war efforts, which included knitting socks for soldiers, and providing assistance to soldiers’ families in Montreal.

Soldiers of the Soil

By 1915, the Canadian government began pushing for increased food production on Canadian farms. As more food was needed on the front, so too was the increased need for workers on Canadian farms. Although conscription began in 1918, many farmers were exempt, as their work was considered vital to the war effort. However, as the war drew on, the need for agricultural workers increased. The Soldiers of the Soil (SOS) was a national program created by the Canada Food Board that was geared toward high school children from urban areas. The students lived and worked on farms for three months and were even excused from completing their final exams. SOS members received military-style uniforms and were awarded bronze medals at the end of their service. The SOS was advertised in many newspapers across Canada including the Montreal Gazette. In Quebec alone, 14,800 individuals participated in the program.

In Ontario, many women were asked to join the Farm Service Corps. These “Farmerettes” worked in various aspects of food production, from picking fruit to canning. Lois Allan was one of 100 women, including two from Quebec, who worked at E.D. Smiths and Son’s Jam factory in Winona, Ontario shucking berries in the spring of 1918. The work at the factory was long and hard. A typical day for Lois and the other farmerettes consisted of ten to twelve hours working at the factory. However, like most of these women, she felt that being a farmerette was a way of “doing her bit”. A parody song, written by Lois to the tune of Clementine, demonstrates this belief:

“Up at Pine cove at the ball club camp the jolly farmerettes. They pick cherries and all the berries. They’re the farmers’ little pets.

O the tall ones, o the small ones, o the jolly farmerettes they are workers they’re no shirkers each earns every cent they get.

We are called the N S workers, we are soldiers of the soil; we’ve no sympathy with shirkers and the slakers make us boil.”

Food on the War Front

Food was of course also a concern for soldiers fighting overseas. It is easy to think that solders only had access to tinned foods and hardtack (a bland, dry, and long-lasting cracker). However, the types of food available to a soldier were largely dependant on how close to the line they were. Some units were fitted with horse drawn field kitchens. Others used “Aldershot ovens” that were built in the rear of the line. There was approximately one cook for every 100 men. Many military cooks were trained at the Canadian School of Cookery in London.

Although they played an important role in the war effort, cooking was still not considered work normally done by men at the time. Other soldiers often believed that being a cook was easy and safer work. This was often not the case. Letters written by gunner and cook, W. J. Johnston, to his brother demonstrate that being a cook did not get you out of the line of fire. During one incident, Johnston was hit by mustard gas and lost his ability to speak for a month. He also states, “out of 9 cooks which we have had, there is only one fellow and myself left.” His surviving notebooks offer us a glimpse into the recipes being taught to students at the three-week training course at Canadian School of Cookery. This includes the following recipe for Canadian Stew:

“Wash, soak and rewash then cook the beans for 2 hours. Slice the bacon and add syrup, pepper and mustard to the beans. Place a layer of bacon on the dish, then a layer of beans, then layer of onions sliced and continue in this way ‘till pan is filled. Cover with stock and cook in moderate oven for 1.5 hours”.

Whether on the front, or at home, the First World War drastically impacted the way Canadians ate. Surviving recipes and cookbooks from the war show the resiliency of Canadians at a time of crisis and food shortages. Many of the recipes put greater emphasis on homegrown local food, and sustainability, which is equally important today as it was a century ago. Why not try one of these recipes for yourself!

For more wartime recipies see: Win-the-war: Suggestions and Recipes (ca. 1916). Or Recipes for Victory (information below).

Article written by Anthony Badame for Je Me Souviens.

Sources:

- “Farming and Food“, and “Food Fuel and Inflation“, Canadian War Museum/Musée canadien de l’histoire.

- “Jeanne Anctil“, Culinary Historians of Canada.

- “Legislation and Principal Events“, Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada.

- “Lois Allan Fonds“ and “Clementine“, Library and Archives Canada/Bibliothèque Archives Canada.

- “What Canada Has Done“, Canada Food Board.

- “What WWI can teach us about hoarding toilet paper“, Television Ontario.

For a more academic approach:

- Baird, Elizabeth and Bridget Wranich (2018). Recipes for Victory, Whitecap Books: Toronto.

- Driver, Elizabeth (2008). Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949, University of Toronto Press: Toronto.