Since November 2002, the late-May holiday has been recognized as National Patriots’ Day by the Quebec government. Previously known by other names such as the Fête de Dollard, or the Queen’s Birthday, this day actually has a rich military tradition that is often forgotten.

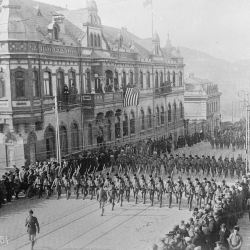

Victoria Day was first celebrated in the United Province of Canada in 1845. The chosen date was May 24, or Queen Victoria’s birthday. Traditionally, a monarch’s birthday was a day for a military parade, as is still the case in the United Kingdom with the “Trooping the Colour” event. In United Canada, this day soon became a statutory holiday. As few parades were held on Canadian soil, the day marked the start of mandatory annual training for local militias.

With their different social and historical context, Francophones never really celebrated the Queen like Anglophones do. In the 1920’s, French Canadians unofficially renamed the day the Fête de Dollard in honour of Adam Dollard des Ormeaux, a hero of the legendary 1660 Battle of Long Sault.

Following the Quiet Revolution, Quebeckers rediscovered the history of the 1837 and 1838 rebellions and gradually associated the name of Jean-Olivier Chénier (Patriote leader at the battle of Saint-Eustache) with the May holiday named after Dollard des Ormeaux. In 2002, the Quebec government adopted the Monday before May 25 as National Patriots’ Day.

The Rebellions of 1837-1838

Why Patriots’ Day? At the time of the change, the government wanted to highlight the significance of the insurgents’ struggle. While the name “National Patriots’ Day” only exists as such in Quebec, the rebellions of 1837 to 1838 took place in both Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) and Upper Canada (present-day Ontario). Although each colony had its own rebellions, the demands and grievances were not the same.

The rebels of Upper Canada, led by people like William Lyon Mackenzie (the first mayor of Toronto, which was previously called York), fought primarily for a change to the land-grant system and for responsible government. After the rebels seized a Toronto armoury, they suffered three defeats by the British army. After this much shorter and more disorganized conflict compared to the one in Lower Canada, over 200 men fled from Upper Canada to the United States. Although the insurrection did not have the impact of the rebellions in Lower Canada or the American Revolutionary War, it was impossible for the Crown to ignore the uprising.

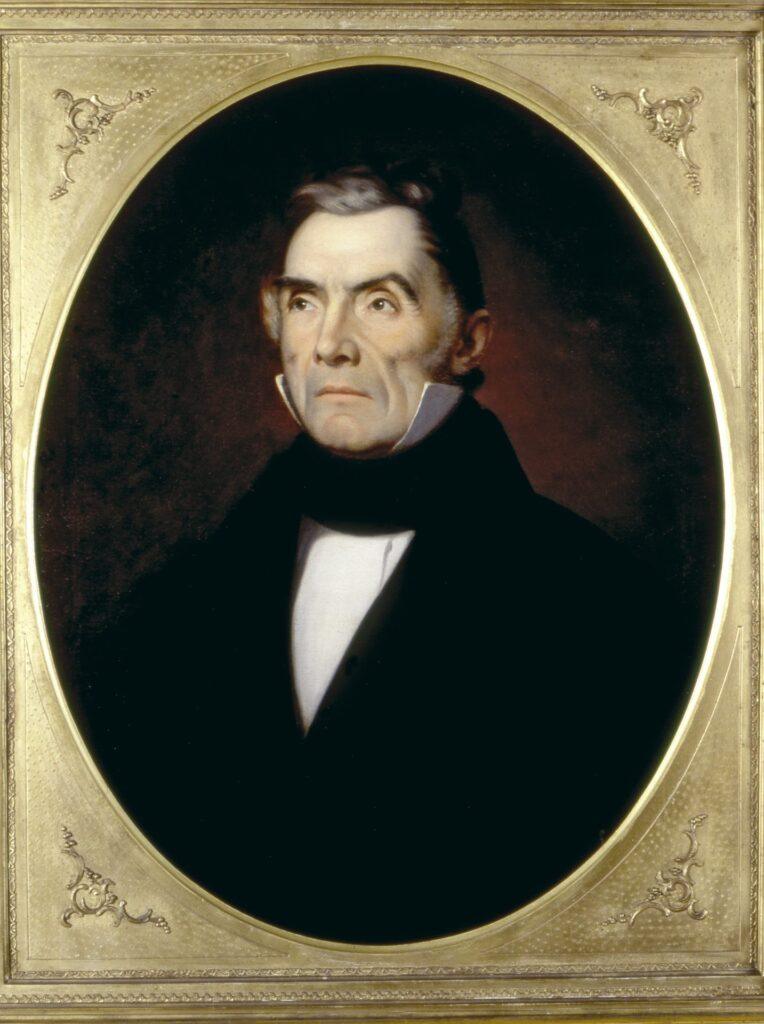

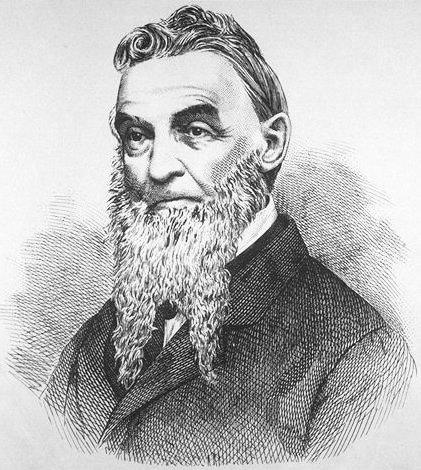

Right: Louis-Joseph Papineau was a very important politician at the time. He later became the leader of the patriots (source: The Canadian Encyclopedia).

In 1834, the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada adopted 92 resolutions, which were mainly requests and grievances about the colony’s political system, as few powers were granted to elected officials. The Legislative Council was appointed by the Governor and not selected from the pool of elected members. The British government debated the resolutions in London, but they did not have widespread support. In response, the 10 Russell resolutions (named for Lord John Russell, Britain’s Colonial Secretary) rejecting all demands from Papineau’s Parti patriote were adopted in 1837 by the British Parliament.

Although political tensions were a cause of the conflict, they were not the only one. Control of land by the Crown, the arrival of Loyalists following American independence, Francophobic governors, and the need to emancipate French Canadians were also among the many causes of the insurrection. The discord was so great that, in fall 1837, most of the British troops in Upper Canada were transferred to Lower Canada.

Everyone in Lower Canada chose a side. Paramilitary associations such as the Doric Club (Loyalists) and the Sons of Liberty (Patriotes) had skirmishes in the fall of 1837 even before military conflict broke out. The clergy, managed by Monsignor Lartigue, took a stand with the British authorities. However, many country priests were sympathetic to their congregations and supported the Patriote cause.

On November 23, 1837, the British army led by Lieutenant-Colonel Gore had its first battle against the Patriotes, who were commanded by Dr. Wolfred Nelson. This battle pitted 300 British soldiers against 200 besieged Patriotes. The battle of Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu began early in the morning and ended around 3:00 p.m. The army was ordered to retreat by Lieutenant-Colonel Gore, as Patriote reinforcements began to arrive from nearby villages. This battle was the Patriotes’ only victory for the entire conflict. A dozen people were killed on both sides.

Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu was the scene of the second battle two days after the battle of Saint-Denis. About 250 Patriotes set up barricades around the seigneurial manor in preparation for the battle. Many residents, including women, children and the elderly, helped get ready for the ensuing fight. Colonel Wetherall and his 450 soldiers attacked the village and left a bloodbath, as about 30 British troops and over 150 Patriotes lost their lives. Many Patriote leaders and hundreds of insurgents left the colony for the United States. Others were arrested and taken to Pied-du-Courant Prison.

On December 13, 1837, General Colborne and the British troops left Montreal for Saint-Eustache, a village in the county of Deux-Montagnes. The next day, when 1500 men arrived, the Patriotes sounded the bell tower alarm to warn the village. About 200 Patriotes led by Jean-Olivier Chénier went out to fight the army and were met with salvoes of fire. Retreating to the village, the Patriotes took refuge mainly in the church and then in the convent, the presbytery, and neighbouring houses. Around noon, the village was surrounded by British troops, who fired cannonballs at the buildings in which the Patriotes were sheltering. To this day, cannonball marks are still visible on the church.

When the buildings managed to withstand the onslaught, Colborne ordered his men to break down the doors. However, the soldiers had to retreat when the Patriotes fired back and prevented them from entering. Gradually, troops of soldiers managed to enter the buildings and set them on fire. The presbytery was the first to be burned down, followed by the manor house, the convent, and finally the church. The trapped Patriotes were forced to jump out of windows under British fire. The bullets found their mark in many, including Chénier, who took two bullets to the chest. Around 4:30 p.m., the village was in flames. About 65 houses were looted and then destroyed by fires set by the British soldiers and loyalists.

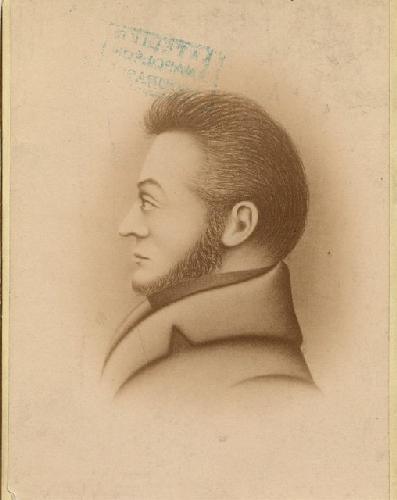

Top, left: François-Marie-Thomas-Chevalier de Lorimier found himself in Saint-Eustache during the battle (seen on the top right). He managed to flee to the United States and led the second insurrection in 1838. He was then captured and hanged on February 15, 1839.

Following the 1837 defeat, many Patriotes fled to the United States. From there, they planned various invasion attempts and strategized battle plans. In the end, the second insurrection of 1838 ended in failure. The first invasion attempt was stopped by American border patrols under the young country’s stance of neutrality, and the second was foiled by the British army. During the subsequent battles of Beauharnois, Lacolle and Odeltown, the Patriotes suffered defeat after defeat.

In the wake of the 1837-1838 rebellions, the Patriotes were sent to Pied-du-Courant Prison, some were sentenced to exile in Australia and Bermuda, while twelve of them were hanged. In 1838, the British Parliament sent Lord Durham to investigate the causes of the rebellions and the discontent of the colonists. In 1839, he finished his report, which had three sections: Upper Canada, Lower Canada and a decrease in French-Canadian autonomy.

According to Durham, the French Canadians had no history, no culture, and no literature and were directly responsible for the insurrections. In his view, the two parts of Canada had to be united to drown what he called inferior people in a sea of British subjects.

The 1840 Act of Union unified the two provinces, but the French-speaking population was not assimilated. The French Canadians responded with actions like the Revanche des berceaux. This tactic pushed by the Catholic clergy began around 1755 at the start of the Acadian Expulsion and continued until the 1960s. To counter assimilation and the massive increase in English-speaking colonists, the idea was for French Canadians to have a higher birth rate.

Conclusion

National Patriots’ Day was established by Bernard Landry’s government to recognize the significance of this military conflict and its impact on Quebec and Canadian society. Although the Patriotes lost most of their battles, their struggles left a deep cultural legacy:

- Responsible government implemented in 1848.

- The adoption of English and French as the official languages of Canadian Confederation.

- The creation of a French-speaking province with the establishment of Canadian Confederation.

- An increase in the birth rate among Francophones pushed by the Catholic clergy, which lasted until the 1960s.

- The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion.

- Many monuments, including one at Pied-du-Courant Prison in Montreal.

- The song Un canadien errant written in 1842 by Antoine Gérin-Lajoie (and covered by Leonard Cohen in 1979).

- The song Chant d’un patriote by Félix Leclerc, recorded in 1975.

- The novel Family Without a Name by Jules Verne, published in 1888.

- The novel Enfants de la rébellion by Suzanne Julien, published in 1988.

- The novel Nuits rouges by Daniel Mativat, published in 2008.

- The film Les maudits sauvages by Jean Pierre Lefebvre, released in 1971.

- The film Quelques arpents de neige by Denis Héroux, released in 1972.

- The film Quand je serai parti… vous vivrez encore by Michel Brault, released in 1999.

- The film 15 février 1839 by Pierre Falardeau, released in 2001.

- And many other works and events, including National Patriots’ Day!

Article written by Alexandrine Bleau-Quintal for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (www.traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

A number of books in french has been written about the Lower Canada Rebellion. We leave you a selection right here:

- Jean-François Cardin, Claudine Couture et Gratien Allaire, Histoire du Canada. Espace et différences, Québec, Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 1996, 400 p.

- Jean-Pierre Charland, Histoire du Canada contemporain : de 1850 à nos jours, Québec, Septentrion, 2015, 344 p.

- Jacques Lacoursière, Histoire populaire du Québec, tome II : De 1791 à 1841, Québec, Septentrion, 2013, 648 p.

- Gilles Laporte, Brève histoire des Patriotes, Québec, Septentrion, 2015, 200 p.

- Paul-André Linteau, René Durocher et Jean-Claude Robert, Histoire du Québec contemporain, tome I : De la Confédération à la crise (1867-1929), Montréal, Boréal, 1989, 758 p.

Several websites also have a lot of very complete information about the rebellion and the patriots’ day:

- “92 Resolutions”, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “Bibliography of the 1837–38 insurrections in Lower Canada”, Wikipedia.

- “Définition de Gouvernement responsable”, Assemblée nationale du Québec (in french).

- “Fête de la Reine, de Dollard ou des Patriotes?”, Accès (in french).

- “Fête de la reine ou de Dollard des Ormeaux”, Réseau de diffusion des Archives du Québec (in french).

- “Liste des patriotes prisonniers, 1837-1838 et 1839-1840”, Site personnel du conteur Michel Faubert (in french).

- “Rebellion in Upper Canada”, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “Un Canadien errant”, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “Victoria Day”, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “What is Trooping the Colour?”, Royal UK.