Every November 11 since the end of the First World War, Canadians pause for a moment to remember and commemorate their veterans. But what are the origins of Remembrance Day? What are its symbols, and how is this day celebrated? Delve into the origins of Remembrance Day and discover its traditions with our article!

Since the end of World War I, Remembrance Day has been celebrated in all Commonwealth countries: Great Britain, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, India, and, of course, Canada. Indeed, on November 11, several celebrations are held to honor the military service and many sacrifices made by the soldiers of these countries. But where does the tradition of Remembrance Day come from, and what does it really mean to Canadians?

From the Battle of Paardeberg to the First World War, the history of this day of remembrance reflects an evolution marked by the duty to remember and recognize those who served. To this end, Remembrance Day has adopted several symbols and traditions to honor veterans, from poppies to songs.

Remembrance Day and its History

The need to honor fallen soldiers did not come out of nowhere. On the contrary, it is part of a long tradition of honoring the military. Beyond erecting statues or monuments, it was also important, according to local governments, to provide an opportunity to gather and commemorate soldiers: both those who lost their lives and those who survived.

In Canada, the first forms of public commemoration came, unsurprisingly, directly from Great Britain. Indeed, in 1899, Canada, then a dominion of Great Britain, engaged in its first major overseas operation: the Boer War. On February 27, 1900, Canadian troops took part in the Battle of Paardeberg. Resulting in a decisive victory in the war, the participation of the Canadians was highlighted as instrumental to its success.

Upon their return, Canadian veterans of the Boer War quickly began organizing festive gatherings to celebrate their participation. These evenings combined dinners and dances with more commemorative elements to remember the 267 Canadians who had died during the war.

Paardeberg Day continued to be celebrated among veterans and their families until Armistice Day on November 11, 1918. For Canada, it goes without saying that the First World War (1914-1918) was the largest conflict it had experienced as a nation to date. Armistice Day, which fell on November 11, marked the end of fighting until the Treaty of Versailles was signed afterwards.

In the early years, Armistice Day was celebrated in much the same way as Paardeberg Day, but on a larger scale. On a Monday chosen somewhere in November, it became customary for veterans, families of the deceased, and their loved ones to gather privately or in a public place to commemorate the fallen. It was not until the 1930s that this practice became increasingly popular, attracting the general public and elected members of government. Remembrance Day, as we know it today, gradually took shape.

The forms and symbols of commemoration

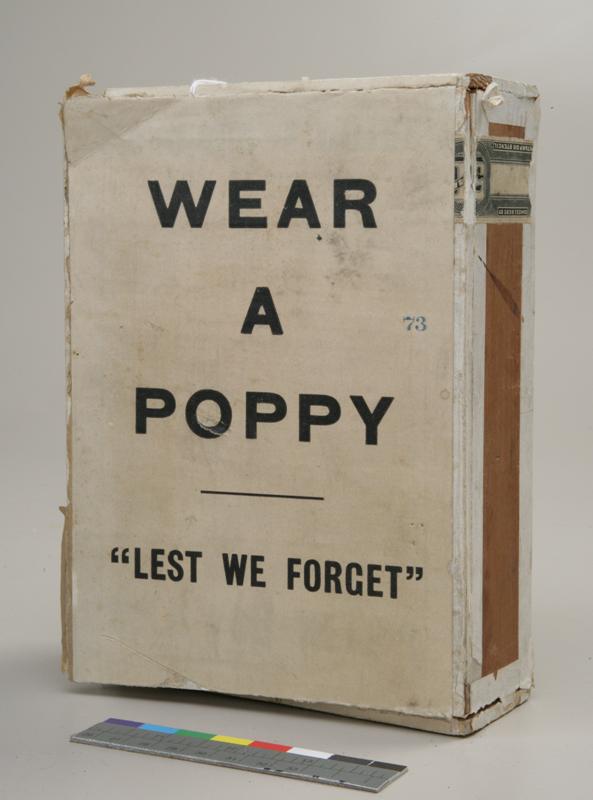

In Canada, Remembrance Day is usually celebrated by wearing a poppy on the chest in the weeks leading up to it. Why poppies? These flowers grow particularly well in soil that has been freshly turned. Due to bombs, trenches and the movement of troops, the ground was particularly disturbed during the First World War. As a result, many poppies could be seen all over the European territory affected by the war. Many soldiers wrote about them in their letters home.

The Canadian soldier John McCrae is particularly well known for his poem “In Flanders Field” relating the presence of poppies. McCrae wrote his poem on May 3, 1915, after attending the funeral of one of his friends and noticing several poppies growing nearby. He later published his poem, which was very well received in Canada.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

– John McCrae

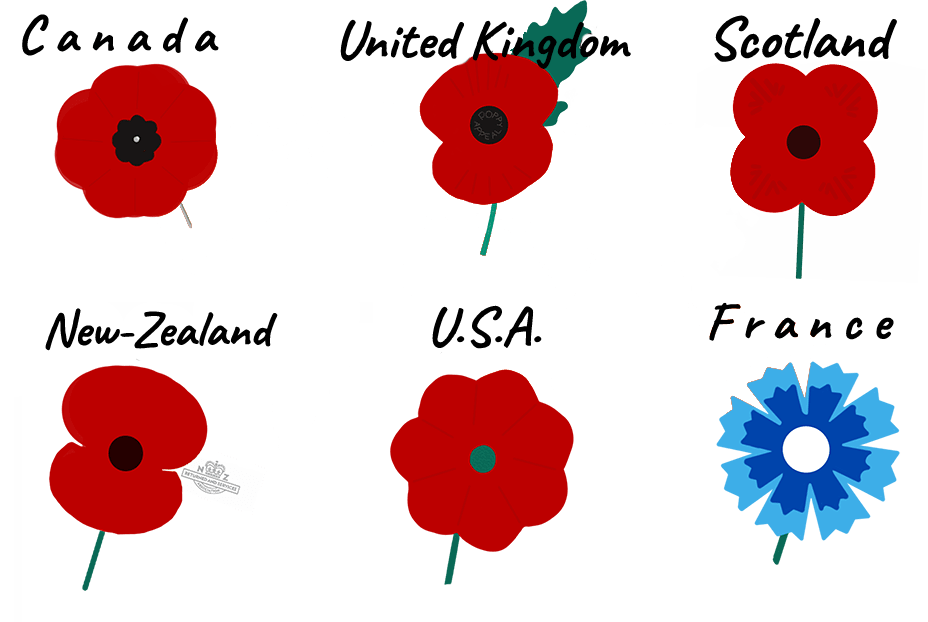

Thus, this flower progressively became the symbol of Armistice Day and, later, Remembrance Day. It should be noted that the poppy was also adopted by other countries and in other forms. For example, in 2006, the purple poppy was adopted in remembrance for all the animals that served during wartime.

On November 11, several parades are organized in various cities and municipalities. Local military units that have been granted Freedom of the City are also invited to take to the streets to parade in honor of their past and present members. Accompanying these parades and celebrations, one or two minutes are observed to reflect on veterans, both living and deceased. Some entities also hold special masses in addition to parades and ceremonies.

In Ottawa, a ceremony is held every year. The ceremony comprises a number of significant components, but the most important of these is a sequence made up of a trumpeter playing the “Last Post”, followed by a two-minute silence, and finally the “Reveille”. These moments are directly inspired by military practices. The “Last Post” signifies that the last post, or position, has been inspected and everyone can go to sleep. The “Reveille” marks the waking hour and the beginning of a better day. This sequence is followed by 21 cannon shots. Finally, the Act of Remembrance is recited in French, English and Aboriginal languages by a veteran.

Commemoration as a civic act

Remembrance is as much a social act as it is an individual one. In the context of Remembrance Day, the individual is not obligated to participate in the many ceremonies. Many are content to simply wear a poppy. However, this simple and very personal gesture can lead to deep reflection. What is commemoration for you and how is it enacted in your life?

All around us, traces of the past and the sacrifices of our ancestors are present. Commemoration, even in its simplest form, is a way of anchoring ourselves in our territory and creating our own identity in relation to our surroundings and their past. Whether it is through Remembrance Day ceremonies, museum exhibits or small signs of commemoration on a street corner, their implications and symbolism are unique and personal to each person who encounters these commemorative markers of the past.

By highlighting certain objects and places that might seem commonplace through commemorative names or symbols, it is possible to understand and become personally anchored in one’s past. Moreover, by remembering the different tragedies of our history, it allows us not to aovid repeating the mistakes and atrocities that took place before. In a way, commemoration as an individual and personal (or social) act enables the continuity of peace, for which many have had to sacrifice greatly in order to achieve it. The First World War was particularly devastating, and the conditions of those who served were very difficult. Commemorating these people on Remembrance Day, as well as all those who have served afterwards, allows us to understand the world we live in today.

Cover photo: People are laying a wreath on Armistice Day in Quebec City, on November 11, 1942 (source: Library and Archives Canada).

Article written by Aglaé Pinsonnault, and updated by Julien Lehoux, for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Marina Smyth. Originally published on October 21, 2022, this article was updated and republished on November 11, 2025.

In 2025, Je me souviens released its Remembrance Day module to help teachers approach Remembrance Day and related commemorations in a different way. View the complete module here.

Sources:

For a more academic approach:

- Debra Marshall, “Making sense of remembrance“, Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 5, no. 1, 2004, pp. 37-54.

- Barry Schwartz, “The Social Context of Commemoration: A Study in Collective Memory“, Social Forces, vol. 61, no. 2, 1982, pp. 374-402.

- Jay Winter & Emmanuel Sivan (dir.), “War and Remembrance in the Twentieth Century“, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999, 272 p.

We also recommend our Remembrance and Bravery activity for students in grades 3 to 6, which traces the history of Remembrance Day.