THE WAR COMES

TO HONG KONG

JAPAN THE CONQUEROR

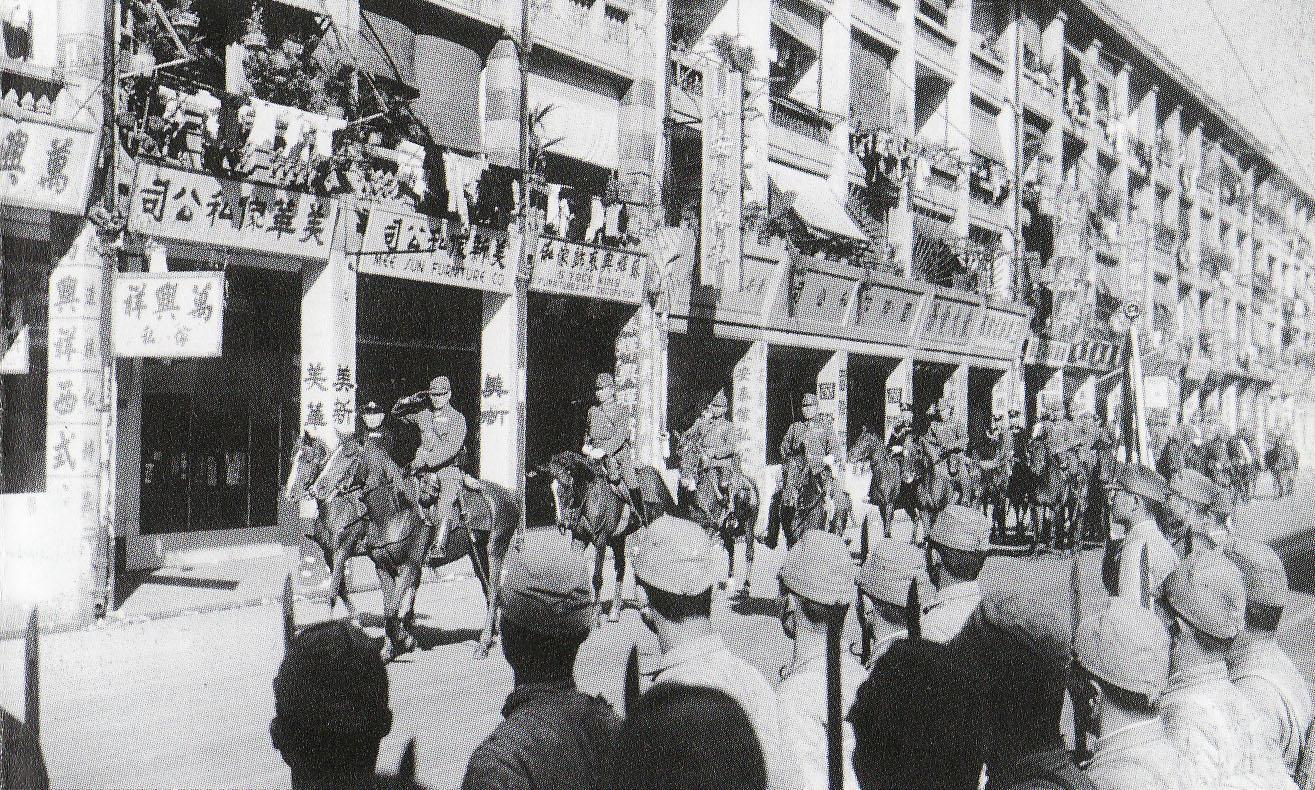

Like Germany and Italy, Japan also sought to expand its territory after the First World War. Although it claimed it wanted to liberate Asia from white colonizers and create an “Asian co-prosperity sphere,” Japan was actually looking to form its own colonial empire.

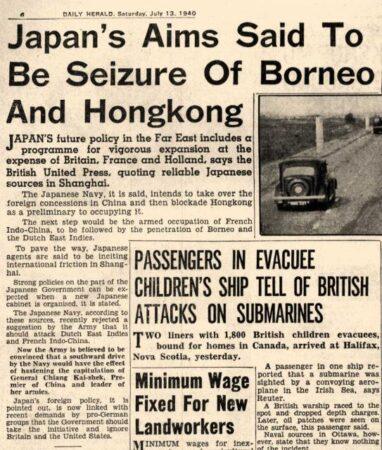

After annexing multiple islands around the Japanese archipelago, Japan’s army turned to the mainland to first invade Manchuria and then China. In 1940, when France had become occupied by Germany, Japan attacked French Indochina. For the United States, Britain and the Netherlands, all of whom occupied significant territories in Asia, this was the ultimate sign that Japan was a true threat.

These fears materialized on December 8, 1941, when the Japanese army launched a surprise attack on the island of Pearl Harbor. At the same time, it coordinated attacks on other Western territories, such as the Philippines, Malaysia, Guam and, finally, Hong Kong.

JAPANESE CONFLICTS

HONG KONG BECOMES VULNERABLE

The Chinese Qing empire (1636-1912) ceded the Hong Kong region to Britain after the Opium Wars in the mid-19th century. This small territory was comprised of Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, and the New Territories. The majority of its inhabitants were Chinese; however, a small, privileged class of people of Western origin governed the region’s affairs.

Japan’s aggressive stance directly threatened Hong Kong in the 1940s. The British deemed Hong Kong to be largely undefendable and called in reinforcements.

Canadians arrived in Hong Kong on November 16, 1941 to an enthusiastic crowd, which mistakenly believed that the new troops would effectively shore up the colony. As the soldiers trained over the next three weeks, they also spent time enjoying the camp’s services; they ate out at restaurants and got hair cuts, shoe shines, and even tattoos! In essence, few people took a Japanese attack seriously.

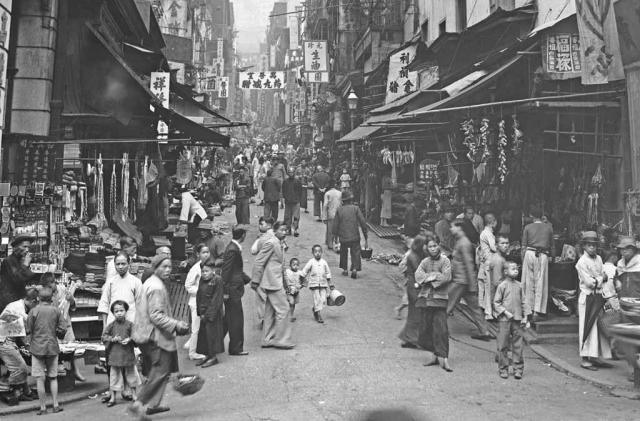

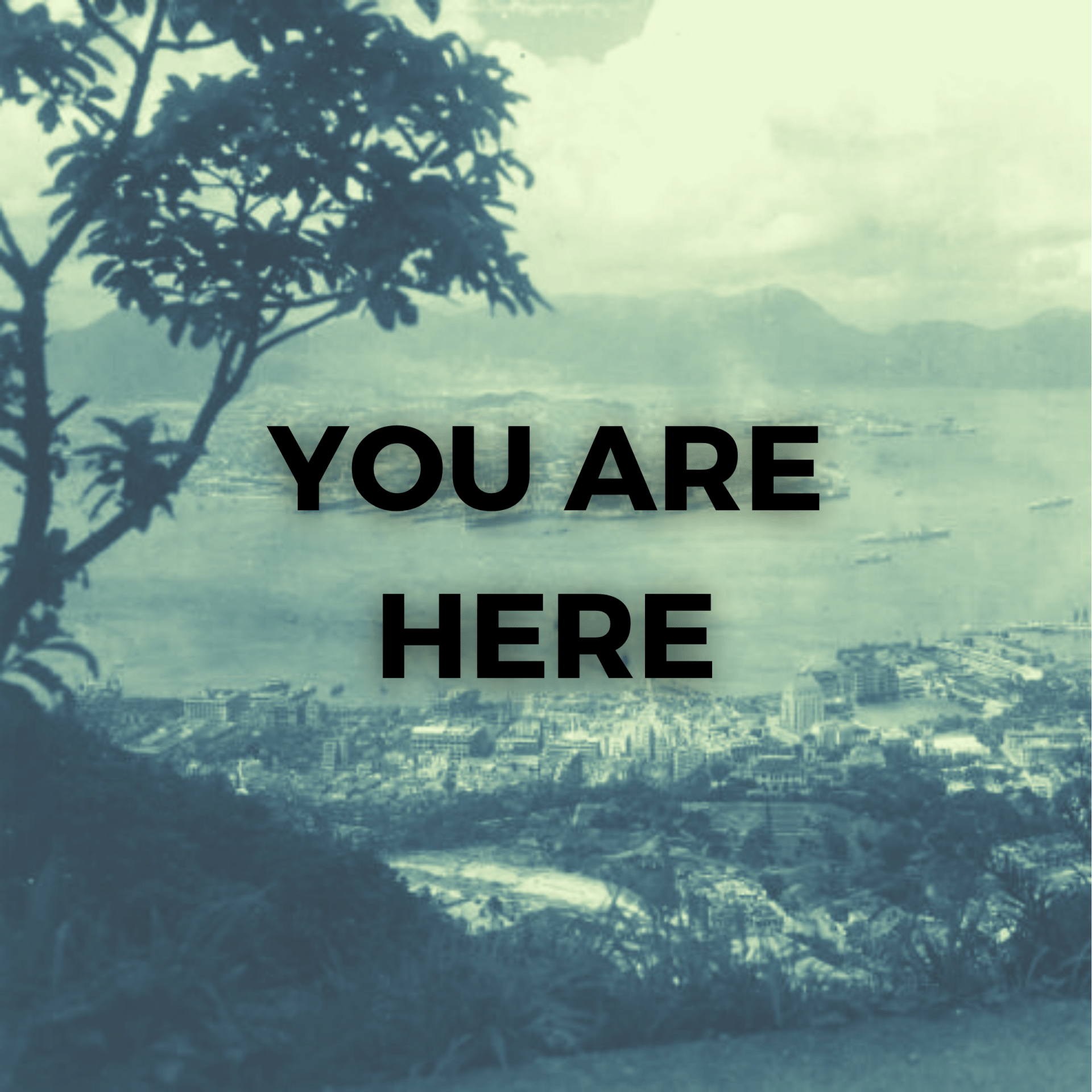

Above: Taken on May 1, 1933, this photo shows a busy shopping street in Hong Kong.

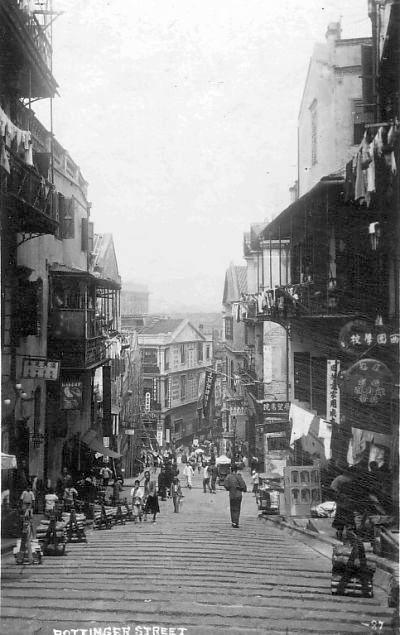

Right: Pottinger Street and its long pedestrian stairs, taken somewhere in the 1930s. Note, on the right, the small paper installation used to celebrate the Double Ninth Festival and honor one’s ancestors.

THE ALLIES’ STRATEGY

Europeans living in Hong Kong were largely unaware of the Japanese threat that hung over the colony. For them, the war was in Europe. Moreover, many of the officers stationed there were confident of the colony’s defensive capabilities. They were convinced that any enemy attack would come from the sea and therefore positioned most of their military resources accordingly.

On the landward side, Hong Kong Island and Kowloon Peninsula were protected by the Gin Drinkers Line, a defensive line comprising bunkers, machine gun nests and artillery batteries. However, many officers were under the absurd impression that the Japanese were unable to see at night because of their slanted eyes and would therefore never attempt a ground attack.

DEFENSIVE FORCES

It was not only Canadians defending Hong Kong during the battle. The Allies numbered about 14,500 in all and included two British battalions (the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots and 1st Battalion Middlesex Regiment), two Indian battalions (the 5/7th Rajput Regiment and the 2/14th Punjab Regiment), along with four artillery regiments. There were also several thousand British, native Hongkongers and Chinese who joined the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force to support the Allies.

They were backed by a number of Chinese troops commanded by Admiral Chan Chak of the Guomindang Navy. The latter was instrumental in thwarting the efforts of several triad militias engaged by Japanese troops to sabotage the maneuvers of the defenders during the battle.

CANADA GOES TO WAR

In September 1941, Great Britain believed that it needed reinforcements to defend Hong Kong. The best-case scenario was that the Japanese would be too afraid to attack the colony. In the worst case, the reinforcements would at least hold out as long as possible to protect Singapore, a key strategic point. London had few illusions: the colony was largely undefendable and reinforcements would not change the situation. The idea was to dissuade the Japanese.

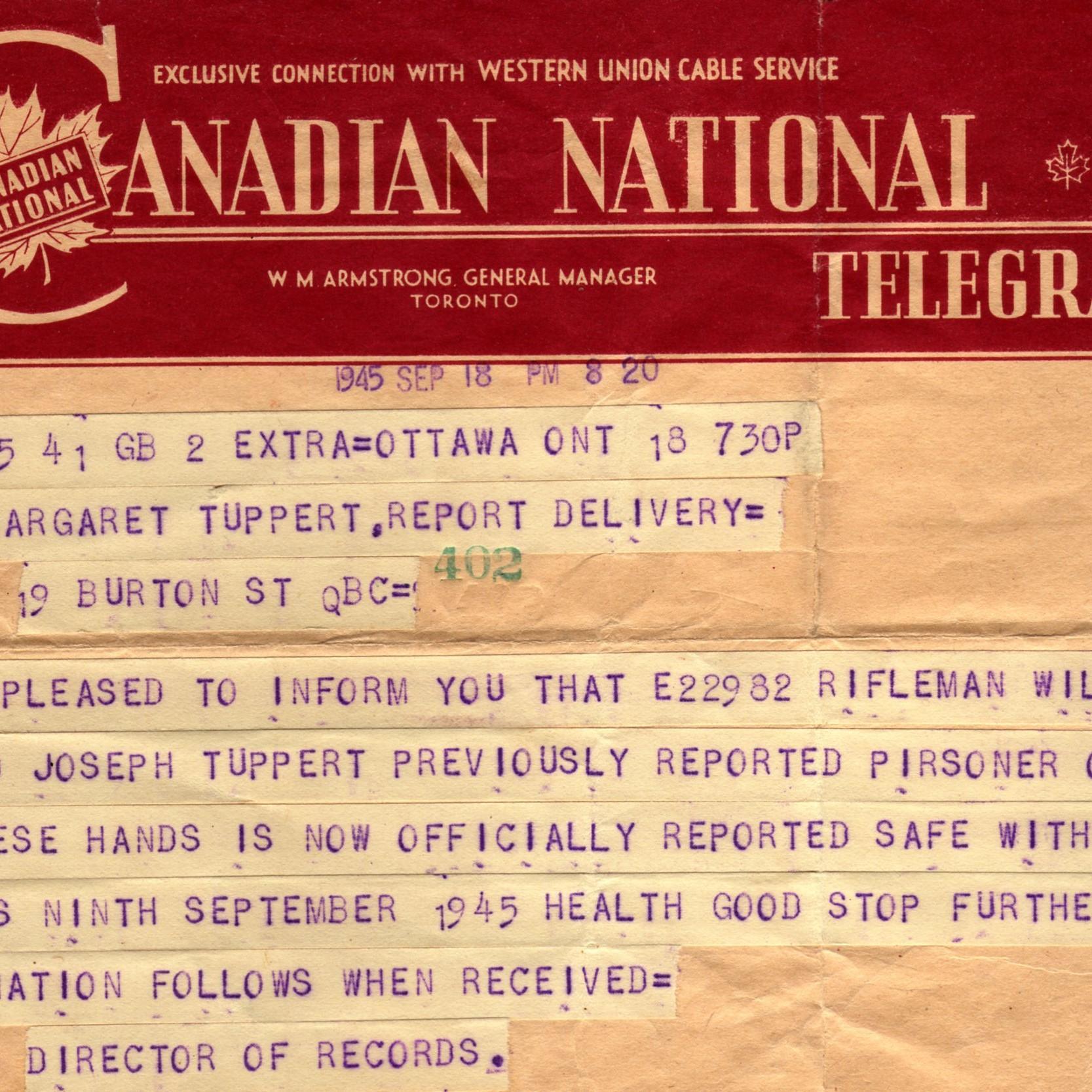

London asked the Canadian government to send two battalions to Hong Kong on a mission with “no military risk.” The request was granted. Canada sent the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers to the colony to form the “C” Force. However, both regiments were poorly trained and had never seen combat.

THE ROYAL RIFLES OF CANADA

Called out on active service in July 1940, this regiment came mainly from the Quebec City area and the Eastern Townships; about 40% of its troops were bilingual Francophones. In October 1941, they boarded a train in Quebec City and, to their surprise, headed west. They had no idea where they were going.

THE WINNIPEG GRENADIERS

Founded in Manitoba, the Grenadiers trained for combat in Europe but were not immediately sent into action. After a first mission in Jamaica, the regiment was called back to Canada before being led to its next mission. The Winnipeg Grenadiers left Vancouver with the Royal Rifles on October 27.