17 DAYS: THE SHOCK OF BATTLE

A DESPERATE GOAL

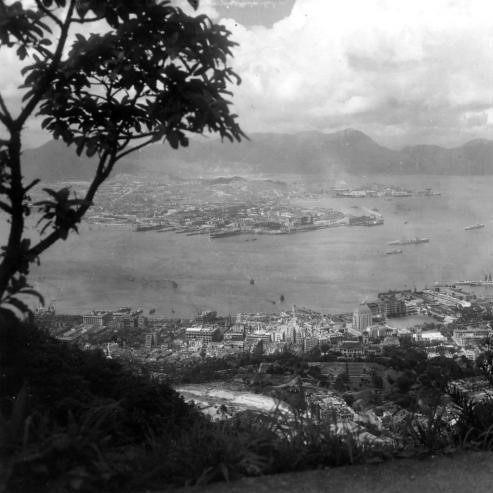

The Battle of Hong Kong was Canada’s first fray of the Second World War. However, defeat was certain from the start of the fighting. The Allies concentrated most of their defences on the seaward side, as they believed that the difficult terrain of the peninsula would block off the Japanese. They also thought that the Japanese soldiers could not see at night because of their slanted eyes. They were therefore taken by surprise when thousands of Japanese soldiers crossed the border the night of December 7th to December 8th and massively attacked the allied positions.

“Hong Kong was an isolated, unprepared military death trap. If the Japanese attacked, we had two options: we could die on the battlefield or become prisoners of a savage enemy.” George S. MacDonnell, Sergeant (Royal Rifles of Canada), date unknown.

The Allies were outnumbered and, in the case of the Canadians, lacked training and equipment. Comparatively, the Japanese troops were veterans of the war in China. The Allies quickly realized their enemy’s superiority. The loss of the Gin Drinkers Line two days later on December 10th was a major blow, as this line had been created to withstand any enemy assault for at least 6 months!

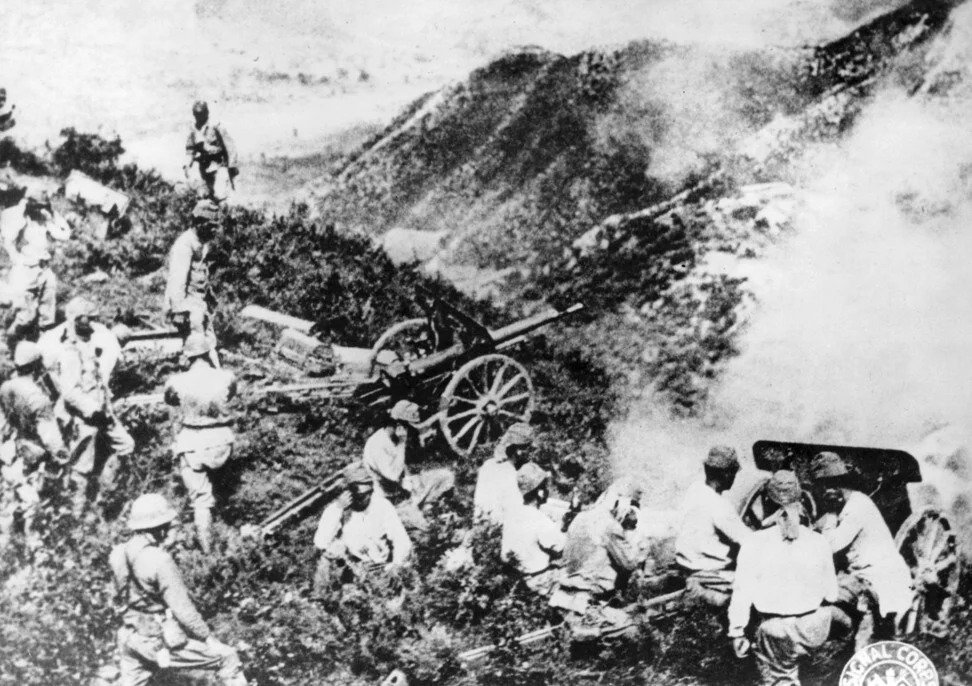

THE CHAOS OF COMBAT

For the Allies, the battle degenerated into chaos: their lines of communication were quickly cut, officers often misunderstood each other, and, to make matters worse, groups of saboteurs attacked their defensive positions. The Japanese advanced rapidly while the Allies struggled to hold their positions. The island was eventually cut in two, and different groups of defenders were isolated from each other.

They attempted a number of desperate manoeuvres. On December 19, the “A” Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, led by Sergeant Major John R. Osborn, retook Mount Butler. The Japanese counterattack was fierce, and Osborn died after throwing himself on a grenade to save his comrades. Three hours later, after intense fighting and heavy losses, the company withdrew from the hill.

A HEROIC DEFENCE

This is not to say that the Allies, and the Canadians in particular, did not show heroism. The Wong Nai Chung Gap was a key strategic position for the defenders. The Winnipeg Grenadiers, along with other troops, defended the pass for three days. The losses were immense on both sides, as all Canadian troops either fell or were wounded. The Japanese ultimately took the pass, but only after overcoming a fierce defence.

Although their forces had already signed the surrender, the “D” Company of the Royal Rifles launched a desperate assault on the Japanese on December 25th at Stanley Village. The Canadians drove the Japanese from their positions but only after engaging in hand-to-hand combat and sustaining heavy casualties. However, this small victory did not change the course of the battle, as the Allies had already surrendered.

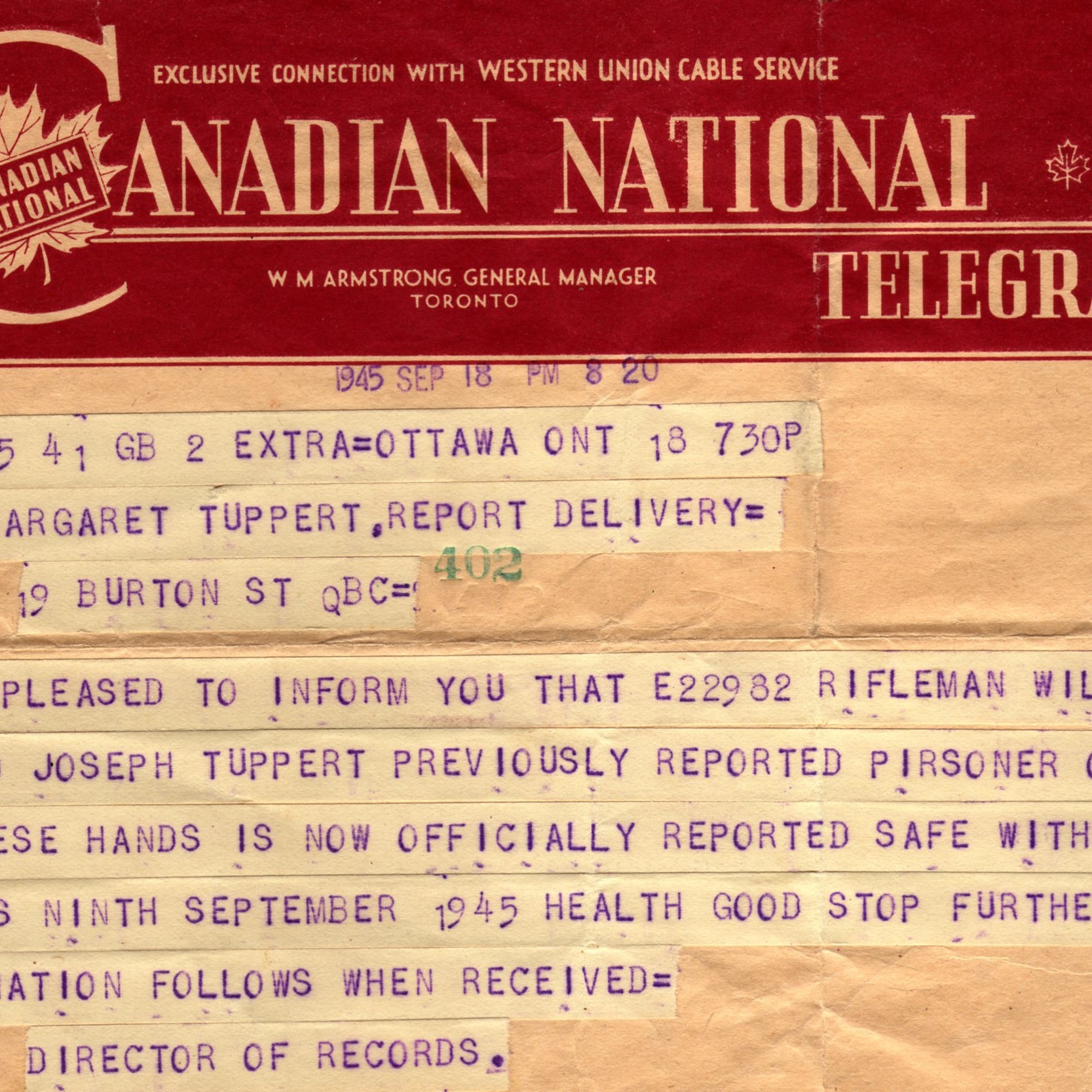

ORGANIZED BUTCHERY

The battle was notorious for its brutality, as the defenders lost all of their men. The Japanese showed no mercy and surrender was not an option. Many Allied soldiers who yielded to the invaders, or were found wounded, were swiftly executed by the enemy. In acts of unusual violence, Japanese soldiers went to Red Cross hospitals and killed injured soldiers and medical staff. The remaining defenders were quickly captured by the Japanese and taken to camps.

“We’re caught like rats, with no hope of escape. [...] I’ll probably never see my old Montreal again.” Georges Verreault, Signaller (Royal Rifles of Canada), December 19, 1941.

TIMELINE OF THE BATTLE