From the outset, the Battle of Hong Kong, from December 7 to 25, 1945, was considered a losing battle. However, the Canadian soldiers of C Force distinguished themselves many times over in their attempts to halt the Japanese advance. This last in a two-part series of articles relates the events of the Canadians’ final attack at Stanley Village.

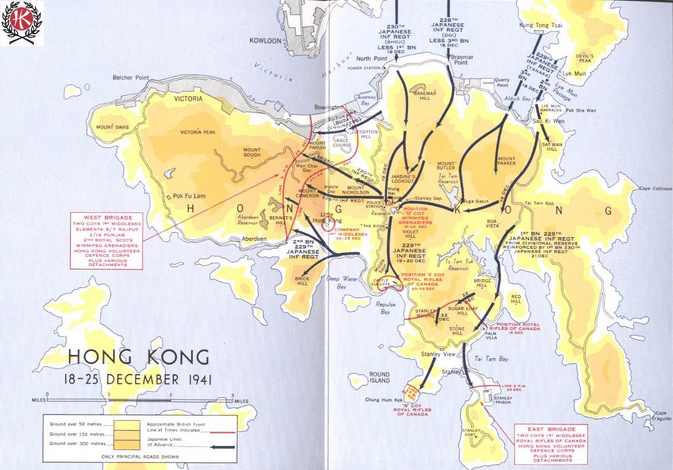

At this stage in the fighting, the Japanese dominated almost the entire island. All Allied positions had been lost, and the battle’s outcome was a foregone conclusion. As we mentioned, the loss of the Wong Nai Chung Gap was a fatal blow that made it impossible for the defenders to retake the island. This loss also meant total victory for the Japanese army.

The Royal Rifles of Canada (RRC), one of the two “C” Force regiments, withdrew to the island’s far end. The RRC skirmished with the Japanese multiple times over a few days, but nothing would be as intense as their final confrontation at Stanley Village. This second in a two-part series commemorating the Battle of Hong Kong takes you through the final charge at Stanley Village on December 25, 1941.

Certain Defeat

After the capture of the Wong Nai Chung Gap, the Japanese army’s advance was unstoppable. On December 24, “D” Company of the Royal Rifles was pushed back from its position and forced to withdraw to Stanley Village. The Stanley Peninsula was an important urban site for the colony, as it had served as the region’s administrative centre in the 19th century. With its buildings and narrow topography, the peninsula was not an optimal fortified position for the Canadians who took refuge there.

Elsewhere on the island, small pockets of resistance fell one by one. For their part, the Winnipeg Grenadiers managed to repel a final Japanese attack; however, they were ultimately forced to lay down their arms and surrender due to a lack of ammunition. Meanwhile, the 5/7 Rajputs were expelled from Mount Parish and the 230th Middlesex Regiment was completely routed. However, one last group of defenders at the Central Ordnance Munitions Depot, a site nicknamed “Little Hong Kong,” held out until December 27. There, the men had enough ammunition and food for several months, and the Japanese would have sustained heavy losses had they attacked it. Only after negotiating with the Japanese commanders did the British defenders agree to surrender, with all the honours they deserved.

The Ultimate Sacrifice

At Stanley Village, General Cedric Wallis ordered the “D” Company of the Royal Rifles to make a final charge against the Japanese positions. His order was strongly contested by Colonel William Home, who had taken over as the Canadian battalion commander after the death of John K. Lawson at Wong Nai Chung. After all, the battle was already lost. This foray would serve no purpose and only waste the lives of many men unnecessarily. Colonel Home was not alone in this opinion, as other officers considered this plan to be “sheer madness.” After the battle, Sergeant George MacDonell wrote, “Not one of them could believe such a preposterous order.” Nevertheless, the men of the RRC were determined to fight it out to the end.

At 12:30 p.m., 110 soldiers from the Royal Rifles attacked the enemy lines. Although they cautiously advanced from position to position, they were quickly spotted by the Japanese troops. The shooting was sustained and intense. Many Canadians were killed by enemy fire, but retreat was no longer possible, as they were too out in the open. Any attempt to fall back would have resulted in their unit’s complete decimation. The only solution was to keep advancing.

Although a desperate attempt in the grand scheme of things, this charge aimed to force the Japanese soldiers surrounding Stanley Village out of position. Considering the enemy’s superior numbers and position, the Canadians’ only choice was to engage them in direct hand-to-hand combat. Under sustained Japanese fire, the RRC soldiers fixed their bayonets and charged. Despite having machine guns and artillery fire, the invaders were baffled by this desperate attack. They thought that the battle was over and that they were simply dealing with a few resistance fighters, not an organized counter-offensive. They left their position in a panic—a rare move for an army that never considered surrender an option.

Unprepared for hand-to-hand combat at that stage of the invasion, the Japanese lost many men. They also momentarily lost their position at Stanley Village. This was a small victory for the Canadians, who showed that their morale had not been broken from days of hard fighting. However, this small victory came at a huge cost: out of the 110 Royal Rifles involved in the charge, 26 were killed and 75 were wounded. Only about a dozen escape unharmed.

Listen to George MacDonell’s account of the Battle of Stanley Village

Surrender

Under the orders of colony governor Mark Young, at 3:15 p.m. British Major General Christopher Maltby ordered all defenders to cease fighting and surrender. Although the official surrender was announced at 3:30 p.m., the Canadians at Stanley Village kept fighting. Wallis refused to believe the surrender orders and continued to fight as long as his men could muster their efforts. He only became convinced of the surrender at 1:30 a.m. on December 26, at which time he ordered a cease-fire.

The Allied resistance was surprisingly resilient; the Japanese army had planned to capture the island in a day, yet the operation lasted a full week. The Japanese had the advantage of immense firepower and total air control. They invaded the island with massive soldier numbers and air support. The Allies did not have the same resources, and their men were not as well trained or equipped. The Allies struggled to contain the flood of enemy soldiers, and the capture of the Wong Nai Chung Gap sealed the battle’s outcome. Although the battle was lost in advance, the defenders nevertheless fought valiantly.

Cover photo: St. Stephen’s College was converted into a military hospital. After the surrender, Japanese troops massacred the nurses and patients there (source: Library and National Archives of Canada/PA145352).

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens with notes provided by Flavie Vaudry. Translated by Amy Butcher (www.traductionsamyb.ca). This article is the second part of a two-part series on the important fighting during the Battle of Hong Kong. To read the first part on the fighting around the Wong Nai Chung Pass, you can click on the link here.

Sources:

- “Canadians in Hong Kong“, Anciens combattants Canada/Veterans Affairs Canada.

- “Canada and the Battle of Hong Kong“, L’Encyclopédie Canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

For a more academic approach, we suggest the following books:

- Franco David Macri, « Canadians under Fire: C Force and the Battle of Hong Kong, December 1941 », Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, vol. 51, 2011, pp. 237-256.

- Nathan M. Greenfield, The Damned: The Canadians at the Battle of Hong Kong and the POW Experience, 1941-45, Toronto, Harper Collins Publishes, 2010, 462 p.

- Tony Banham, Not the Slightest Chance: The Defence of Hong Kong, 1941, Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 2003, 452 p.

This article was published as part of our exhibition on the Battle of Hong Kong: Impossible Odds. Visit our exhibition to learn more about the history of the Canadian who defended the colony of Hong Kong!