On November 29, 1968, the “Hemispheric Conference to End the Vietnam War” started in Montreal and had a pan-American profile thanks to such guests as Salvador Allende, president of the Senate of Chile at the time. A delegation from North Vietnam, led by Hoang Minh Giam, Minister of Culture of the Democratic Republic, also came to the event along with representatives from the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). Nevertheless, the majority of the 1500 people attending the event were from the New Left movements in the U.S. and Canada. A symbol of the radicalism taken on by African American activism at this time, the Black Panther Party (BPP) captured the attention of the press and other conference participants when they arrived in Montreal at the end of November that year.

The Black Panther Party

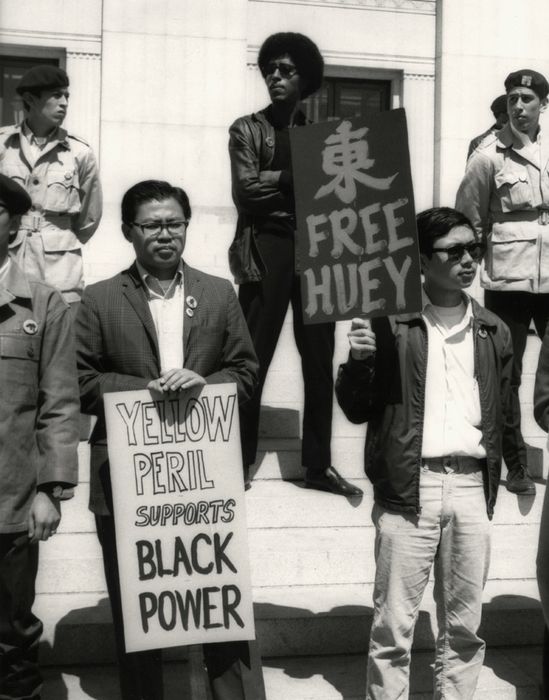

Founded in 1966 by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, two students from Merritt College in Oakland, California, the BPP was part of a process of radicalization of the Black cause in the United States. After the assassination of Malcolm X in February 1965, a younger generation of African American activists who were disappointed with the lack of will to enforce the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act[1] gradually distanced themselves from the traditional nonviolent action advocated by older organizations or leaders, such as Martin Luther King. The discourse of some associations, like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and its leader, Stokely Carmichael, became more radical.

In 1966, Carmichael formulated the concept of “Black Power” that emphasized the need for self-determination for African Americans. This new thinking redefined the Black struggle in the United States and transformed the civil rights movement into a movement for African American liberation. In the wake of Carmichael’s Black Power movement, new organizations like the BPP emerged to take up the idea that Black communities in the United States were colonized inside their own country.

Third world revolution and transnational solidarity

In Montreal, the Black Panthers were represented by their president, Bobby Seale, as well as the party’s chief of staff, David Hilliard.[1] In his keynote speech to open the conference, Seale advanced the idea that the reactionary forces holding back Black emancipation in the United States were the same ones waging war in Vietnam. He linked the two struggles as the same fight against American imperialism, the symbol and embodiment of oppression. For him, the theme of the conference should not be peace but rather support for the wars of liberation around the world. Through this rhetoric, Seale successfully placed his party’s actions within the framework of a transnational revolutionary coalition.

On stage with them were members of the Vietnamese delegation, who explained that their struggle, like that of the Black Panthers, was at the forefront of a Third World revolution that they called for before concluding: “You are Black Panthers, we are Yellow Panthers!”

The next day, local newspapers such as The Montreal Star or Le Soleil and international publications such as French daily Le Monde all reported on the speech by Seale, describing him as an incredible speaker who galvanized his audience and stirred them with the lyricism of his words. By fixing the movement’s leadership within past processes and future actions, the conference concluded with all delegates raising their clenched fists in the Black Panther salute and chanting, “Panther Power to the Vanguard!”

Revolutionary internationalism

The three days of the Hemispheric Conference also saw relations established between the BPP and FLQ based on the solidarity between oppressed people, as Seale spoke about during his speech. Quebeckers and African American activists discussed how each group may have to take refuge with the other. At the start of 1969, to escape arrest for a series of bombings in Montreal, two members of the “Geoffroy” network, Pierre Charette and Alain Allard, found safe harbour in Harlem with the Black Panthers before fleeing to Cuba, where they stayed in exile for ten years.

Again in 1969, Eldridge Cleaver, Minister of Information for the Black Panthers, established the party’s “International Section” in Algiers. In this city, the capital of revolutionaries from all over the world at the end of the 1960s, African American activists reconnected with their allies from North Vietnam and Quebec, as the FLQ had also set up a very official “Foreign Delegation” that, despite having only two permanent members, received funding from the Algerian authorities.

The fight for a new world order

Before expanding across the Atlantic, the foundations of the Black Panther’s internationalization through transnational revolutionary solidarity were laid at the “Hemispheric Conference to End the Vietnam War” during those days in November and December 1968, when Montreal became the local site for a world revolution.

[1] These laws adopted in July 1964 and August 1965, respectively, prohibited all forms of discrimination against Black people and represented significant wins for the rights of African Americans. However, the lack of enforcement in those early years, especially in the southern states, led to disillusionment and prompted many young African Americans to become radicalized.

[1]The BPP thought of itself as an actual government party and structured itself as one.

Cover photo: Bobby Seale delivering his speech during the conference with members of the North Vietnamese delegation by his side (source: Black Panther Newspaper, vol. II, no. 18, December 21, 1968, p. 5).

Article written by Clément Broche, PhD candidate in history at the Université du Québec à Montréal, for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources :

This article mobilized a number of first-hand sources for its writing. Here is a small list of some of the archive sources that were used:

- Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Libération in America, New York, Vintage Books, 1967, 211 p.

- Eldridge Cleaver, Post-Prison Writings and Speeches, New York, Random House, 1969, 211 p.

- David Hilliard, This Side of Glory, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1993, 450 p.

- Raymond Lewis, “Montreal: Bobby Seale-Panthers Take Control“, Black Panther Newspaper, vol. II, no. 18, december 21, 1968, p. 5-6.

- Bobby Seale, “Complete Text of Bobby Seale’s Address“, Black Panther Newspaper, vol. II, no. 18, december 21, 1968, p. 6.

For a more academic approach:

- Paul Alkebulan, Survival Pending Revolution: The History of the Black Panther Party, Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 2012, 196 p.

- Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, Berkley, University of California Press, 2013, 539 p.

- Kathleen Cleaver and George Katsiaficas, Liberation, Imagination and the Black Panther Party: A New Look at the Black Panthers and their Legacy, London, Routledge, 2001, 336 p.

- Sean L. Malloy, Out of Oakland: Black Panther Party Internationalism During the Cold War, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2017, 280 p.

- Elaine Mokhtefi, Alger, capitale de la révolution : de Fanon aux Black Panthers, Paris, La Fabrique, 2019, 279 p. (in french).

- Caroline Rolland-Diamond, Black America : une histoire des luttes pour l’égalité et la justice (XIXe–XXIe siècle), Paris, La Découverte, 2016, 576 p. (in french).