While almost everyone knows how to ride a bicycle, not everyone knows that these machines were also deployed during the infamous Normandy landings. In this short article, Julien Lehoux describes the Canadian Army’s wartime use of these two-wheeled machines.

The Canadian Army and its allies used a plethora of vehicles and transportation methods during the Second World War. From landing crafts to tanks, the Allies designed hundreds of models of motorized vehicles for their military operations. One particularly popular vehicle with the ground army was the bicycle.

Shown to be useful time and again in the field, the bicycle has a very simple mechanical design compared to motorized vehicles, which need thousands of engineers, mechanics and factories for their design and assembly. Bicycles were a go-to transport option during the war for many armies, and the Canadians were no exception.

Wartime transport

Many garrison troops used bicycles as their main mode of transportation, as there was no quicker or more accessible way for a soldier to get around on leave. Bicycles were a mainstay for Canadian soldiers stationed in Great Britain, although they did not have a preference for any particular model. The machine simply had to move on two wheels and they were good to go!

Aside from furlough transportation, bicycles were used to quickly transport infantry en masse from different points during military operations. To compensate for its lack of motorized vehicles in the field, Japan made extensive use of bicycles to move its troops around during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945).

Other armies also adopted the bicycle as a means of transport, with wartime bicycle battalions noted in Denmark, Poland, Finland and Sweden, which had to mobilize and move troops around as quickly as possible when the Nazi army advanced into their territories between 1939 and 1940. Later on in 1944, as Germany seemed to already be losing ground, battalions of the Volksgrenadiers, or infantry units, were forced to travel by bicycle due to the lack of motorized vehicles.

For its part, the Canadian Army did not use bicycles on a large scale to transport its troops. In Italy, where Canada spent its longest campaign of the war, the infantry had to march arduously from point to point. If the soldiers were lucky, they could hitch a ride on a truck! Other exceptions include September 5, 1943, when men from the 48th Highlanders of Canada found a stack of folding bicycles abandoned by the Germans. This fortuitous discovery let the soldiers get to their destinations very quickly

Bicycles were mainly used by dispatch riders, or the troops that carried messages between units. These messengers usually travelled by motorcycle to quickly cover distances. However, the lighter bicycles were much easier to handle during the landings.

Mobilized during the Dieppe Raid, Private Jacques Nadeau of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal was made a dispatch rider just a few hours before the operation! The short-statured Nadeau explained how difficult it was for him to get on the bicycle he was given: “The bicycles were sized for English policemen, who were all over 6 feet tall!” (translated from Martin Chaput, Dieppe, ma prison : Récit de guerre de Jacques Nadeau, Montreal, Athéna Éditions, 2008, p. 51).

Obviously, bicycles were not the easiest to use in the middle of a firefight. During the terrible raid, Nadeau threw his bicycle off the landing craft only to lose sight of it: “I tried to pick out where it landed, but bullets were sizzling all around me. So I just thought to myself, ‘To the devil with the damn thing’,” (translated from Martin Chaput, ibid., p. 59). Fortunately, the Canadian dispatch riders who landed in Normandy did not have the same problems as Private Nadeau.

The dispatch riders in Normandy

Unlike the Dieppe raid, dispatch riders were not deployed for the initial early-morning Normandy landings. The few photos of cyclists taken on June 6 show them disembarking in the middle of a largely secure beach, accompanied by significant contingents of support troops.

The Normandy landings took place in the early hours, when the sun had barely risen. Following the victory at Juno Beach, hundreds of ships followed the first landing craft to unload reinforcements, tanks, and support equipment. As part of the D-Day plan, the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals installed telephone lines so that the units in the field could communicate. However, this Corps did not arrive in Juno until June 8, or two days after the initial landing. In fact, the dispatch riders were the ones who mainly handled communication during those first few days, which is when the bicycles in the photos seem to have been mobilized by the Canadian army.

Photos taken that day indicate that the dispatch riders disembarked from two ships: the HMC LCI(L)-299 and the HMC LCI(L)-125. The first mainly carried members of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (SDG). According to the Juno Beach Centre, the SDG arrived at Bernières-sur-Mer at around 12:20 p.m. but could not advance far due to obstacles set up by the Germans as well as celebrations by the French. They sustained enemy mortar attacks and had a total of 14 casualties, with 1 fatality and 13 injured. The second ship transported the Highland Light Infantry of Canada. This Ontario regiment arrived an hour earlier than their SDG comrades but suffered no casualties.

The Citadelle’s BSA bicycle

In September 2024, the Musée Royal 22e Régiment was proud to acquire a BSA bicycle for its collections. As mentioned above, the Canadian army did not use any particular bicycle model for its troops. This bicycle now housed by the Museum was built by the Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited, a British firm renowned for its vehicles, weapons… and bicycles! BSA built its first models in 1880 and distributed them widely.

During the war, BSA Limited continued to build bicycles for both civilians and the military, as the bicycles in either case required few resources to build and could be used by virtually anyone.

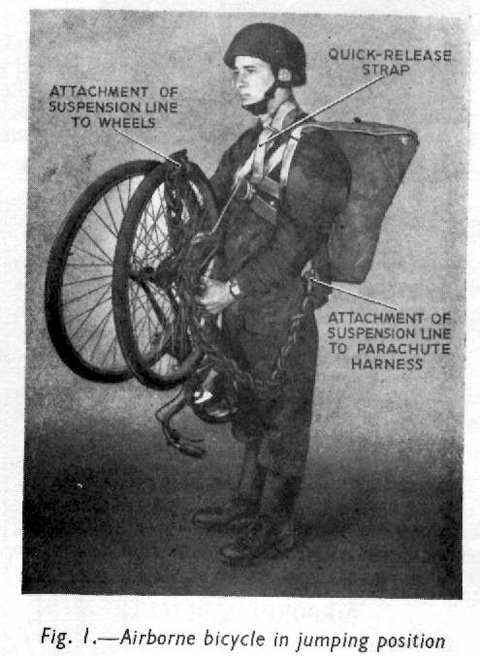

The Model 40 in the Museum’s collection is a folding design ideal for commandos and paratroopers. A soldier could fold up the bike and carry it by hand while parachuting with the rest of his equipment! BSA bicycles in particular were crafted so that the handlebars and seat hit the ground first after a jump.

It is unknown whether the bicycle acquired by the Museum was deployed at the Normandy landings or during an airborne operation. The available information shows that this bicycle was purchased from an army surplus store after the war and then carefully stored for many years. According to the donor, the original owner was very impressed with its mechanical ingenuity!

A little-known weapon in the Allies’ arsenal

When we think of the Normandy landings, or any other military operation at that time, bicycles do not really come to mind as a tool of war for the Canadian Army. However, they were indeed a common way for soldiers to get around both on leave and during war operations.

BSA models are still very popular among collectors, and the Musée Royal 22e Régiment is very lucky to have such a fine specimen in its collection. Indeed, any of these bicycles still with us today should be preserved—and not thrown off a boat or plane!

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca). We’d like to extend our warmest thanks to the Musée Royal 22e Régiment team for sharing their photos of their BSA bicycle!

Sources:

- “1939-1945 WW2 BSA ‘Airborne Bicycle’ Folding Paratroopers Para Bike“, Oldbike.eu.

- “Bicycles in WW2“, Eden Camp Modern History Museum.

- “Highland Light Infantry of Canada on D-Day“, Centre Juno Beach/Juno Beach Centre.

- “HMC LCI(L)-125“, NavSource Online: Amphibious Photo Archive.

- “HMC LCI(L)-299“, NavSource Online: Amphibious Photo Archive.

- “Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders on D-Day“, Centre Juno Beach/Juno Beach Centre.

This article was published as part of our exhibition on D-Day: When Daylight Comes. Visit our exhibition to learn more about the history of the Canadian who landed in Normandy!