The 1960s “Congo crisis” was a complex episode in the history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, here referred to simply as Congo), following its independence from Belgium in 1960. This period was marked by political unrest, ethnic tensions, foreign interventions, and economic challenges, creating a complex and unstable context for the country. In response to these tensions, the United Nations voted to establish a humanitarian mission in Congo called the United Nations Operation in the Congo (Organisation des Nations-Unies au Congo – ONUC). Canada decided to answer the call, sending over 300 soldiers, in addition to thousands of humanitarian workers.

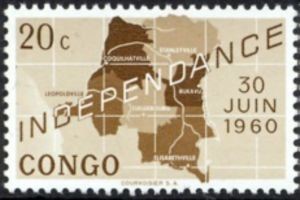

The DRC had been a Belgian colony since the late 19th century under the reign of King Leopold II. During this period, Congo was exploited for its natural resources, primarily rubber and minerals, to the detriment of the local populations. These industries, and their exploitation by the Belgians, led to profound economic and social inequalities. Congolese nationalist movements gained strength in the 1950s, culminating in calls for independence. In 1960, Congo gained independence from Belgium, marking the beginning of a new era. The transition to independent governance happened abruptly, however, leaving little time for the establishment of strong political and administrative structures.

Spreading across a vast territory, Congo is characterized by significant ethnic diversity, with groups such as the Luba, Lunda, Kongo, and others. During the Congo crisis, ethnic tensions were often exacerbated by political rivalries, especially between supporters of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba and President Joseph Kasa-Vubu. These tensions contributed to political and social instability. The Congo crisis was further complicated by foreign interventions, notably from Belgium and the United States. After independence, for example, the resource-rich province of Katanga seceded under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe, with the support of Belgium and several international mining companies. These foreign interventions escalated tensions and complicated the resolution of the crisis.

The United Nations created ONUC in 1960 as a response to the volatile situation. The intent of the mission was to oversee the withdrawal of Belgian troops, to stabilize the situation, and to facilitate a peaceful transition towards independent stability. However, ONUC faced major challenges due to internal rivalries and foreign interference.

In general terms, the Congo crisis of the 1960s resulted from various historical, political, and economic factors. Complex issues, internal rivalries, and foreign interventions contributed to a period of instability with long-term repercussions on Congolese politics and society.

Canada responded to the UN’s call in 1960 by contributing troops, civilian personnel, and diplomats to participate in the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC). Canadian forces, wearing the distinctive UN blue helmets, played a crucial role in maintaining order, protecting civilians, and promoting a peaceful transition to independent governance in Congo. Various regiments joined the effort, including the Royal 22e Régiment. Due to Congo’s colonial past, francophone Canadian military personnel were favoured in selection for deployment. The UN later requested the deployment of French-Canadian signallers, who played a key role in the Congo mission and went on to hold important positions in the UN command structure.

A notable example was the Royal 22e Régiment’s involvement in the Katanga province, which had seceded from the DRC in the crisis. Here Canadian troops faced considerable challenges, from maintaining order in unstable areas to protecting vulnerable civilians. Similarly, the Royal Canadian Air Force provided crucial air support, conducting reconnaissance missions, troop transport, and medical evacuations from the province.

Canadian involvement during the Congo crisis extended beyond military operations. Canadian diplomats were also active in political negotiations, working behind the scenes to encourage peaceful dialogue among different Congolese factions. This multifaceted approach illustrated Canada’s commitment to diplomacy and peace in complex contexts.

The period around the tragic assassination of Patrice Lumumba in 1961 was particularly delicate. The Congolese nationalist Prime Minister was captured and killed in controversial circumstances. His murder had major repercussions on the country’s political stability, reinforcing internal divisions and creating a leadership vacuum. Canadian troops had to operate in an increasingly tumultuous political environment, trying to maintain stability while dealing with challenges posed by rival political factions and heightened ethnic tensions. Canadian military personnel had to operate in a context where political alliances were changing rapidly, and the divergent interests of Congolese factions and international actors complicated the clear definition of the appropriate use of force.

The rules of engagement were strictly defined by the ONUC mandate. Canadian troops were authorized to use force only to defend themselves and to protect civilians in case of direct threats to their security. This often meant that forceful interventions were necessary to prevent violence and maintain stability in vulnerable areas.

Although the use of force was authorized in these specific circumstances, Canada’s mission was deeply rooted in the United Nations’ principles of peacekeeping. The Canadian military sought to minimize civilian casualties and promote long-term stability while adhering to the limits set by the ONUC mandate. When the ONUC troops withdrew in 1964, the situation in Congo remained difficult and turbulent. In the 1990s, a new crisis erupted, leading Canada to return for several weeks. In 1999, the UN established the Crocodile Mission in Congo, which is still active to this day.

In conclusion, Canada’s participation as peacekeepers during the 1960s Congo crisis was characterized by multi-faceted engagement, combining military, diplomatic, and humanitarian operations. Canadian forces operated in a complex environment, strategically force when permitted by the rules of engagement to address on-the-ground challenges while remaining true to the fundamental principles of the United Nations. This chapter in history demonstrates Canada’s ongoing commitment to global peace and its contribution to international peacekeeping efforts in challenging political contexts.

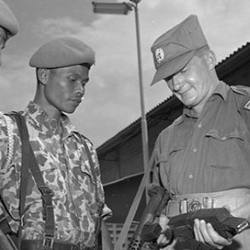

Cover photo: A Canadian soldier shows his Sterling machine gun to two Indonesian soldiers deployed in the Congo, 1961 (source: Government of Canada).

Article written by Aglaé Pinsonnault for Je Me Souviens.

Sources :

- “The Congo“, Gouvernement du Canada/Government of Canada.

- “UN Mission in the Congo: 2 Sept 1960-30 June 1964“, The Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum.

For a more academic approach:

- Michael Carroll, “Canada and the Financing of the United Nations Emergency Force, 1957-1963“, Journal of the Canadian Historical Association/Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 13, no. 1, 2002, pp. 217-234.

- Walter Dorn & David J. H. Bell, “Intelligence and Peacekeeping: The UN Operation in the Congo, 1960-64“, International Peacekeeping, vol. 2, no. 1, 1995, pp. 11-33.

- Daniel Galvin, “A role for Canada in an African crisis: perceptions of the Congo crisis and motivations for Canadian participation“, Mémoire de Maîtrise, University of Guelph, 2004.

- Kevin A. Spooner, Canada, the Congo Crisis, and UN Peacekeeping, 1960-64, Vancouver/Toronto, UBC Press, 2009.