This article was published as part of our exhibition on the Battle of Hong Kong: Impossible Odds.

Visit our exhibit to learn more about the fate of the Canadian soldiers sent to defend the colony!

While the many soldiers sent by Canada to fight in the Second World War have been commemorated time and again for their service, Indigenous veterans have not received the same attention. Official figures show that at least 3,090 Indigenous people, 72 of whom were women, joined the Canadian military during the war, which does not include the thousands of Métis, Inuit and non-registered First Nations people who also reportedly enlisted. By some estimates, 14,000 soldiers from these communities served in the Canadian army during the Second World War.

Fighting in the Second World War with the Canadian Army

Unfortunately, systemic racism plagued the military services at the time, as the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) required their recruits to be of “Pure European Descent and of the White Race” until 1942 and 1943, respectively. The Army also imposed strict health and education requirements that blocked the recruitment of many volunteers from Indigenous reserves. Due to these obstacles, it is estimated that only 29 Indigenous people served in the RCAF, 9 in the RCN, and at least 1,800 in the Canadian Army at the beginning of the conflict.

Many Indigenous people enlisted voluntarily in the military for various reasons. Like other Canadians at the time, many Indigenous people were probably attracted by the benefits offered by the military. With its regular meals, salary and pension, the army represented an attractive option at a time of economic crisis. As one Métis veteran explained:

“Men couldn’t get a job… In the army they paid a dollar-and-a-half [per day]. The most you could get around here for farming or whatever, was a dollar. A dollar-and-a-half sounded awfully good.“

Soldiers such as Charles Byce, Tommy Prince and Brigadier Oliver Martin also had a strong desire to serve Canada and went on to have long careers in the military. Some volunteers had specific reasons for joining, as they feared their treaties with Canada would be annulled if the Axis Powers won. According to Elder Isabelle Mercier of the Mishkeegogamang Nation:

“When an aboriginal person goes in and makes a contract, they will do everything they can to fulfill that contract, and many of our veterans stepped up to ensure that our treaties were secure. Because if the other side won, the other signatory would no longer be able to commit to those treaties and the treaties would be non-existent. This was talked about in my family many, many times.”

The draft that started in 1944 directly affected Indigenous communities, as many men were called up to join the army. In return, some leaders organized protests, arguing that it was unfair to force people to serve a country that did not recognize their basic rights. While we know that some Indigenous people were drafted into the army, it is hard to pinpoint the exact number who served and even harder to know how many were sent to the front lines.

In Hong Kong

Very little formal documentation and research exist about First Nations, Inuit and Métis soldiers. Many soldiers were not registered as Indigenous for all sorts of reasons. This lack of documentation makes it difficult to get an accurate idea of who these soldiers were. While we do know that some Indigenous soldiers served in “C” Force, the military contingent sent to the British colony of Hong Kong in October 1941, we do not know their exact numbers.

According to some sources, 16 Aboriginals served in “C” Force and 9 died during the fighting or while held in captivity at POW camps. Unfortunately, we have little information about them.

In the database of Indigenous soldiers maintained by amateur historian Yann Castelnot, John Murdock Acorn of the Royal Rifles of Canada is listed as being of Mi’kmaq origin. Acorn and his cousin Joseph Amon Acorn reportedly enlisted in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, in 1940. During the fighting, the two cousins were part of a group of soldiers who retreated from the Repulse Bay Hotel, which was seized by the Japanese after intense fighting. They were ambushed by machine-gun fire on their way to their new position and killed instantly.

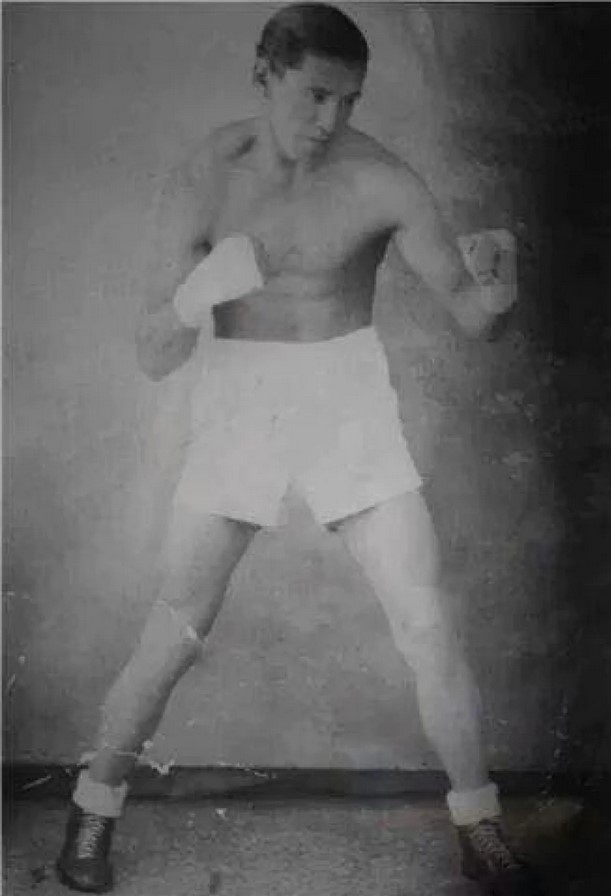

Three other Mi’kmaq soldiers from Listuguj in the Gaspé region, named Paul Martin, Frank Methot and Patrick Metallic, were also in Hong Kong. A boxer before the war, Metallic is described by his grandson, Ivan Gray, as being very involved in his community. All three voluntarily enlisted in the army. As Ivan Gray explains:

“[…] they didn’t have the right to vote as Canadian citizens. And […] it was just out of, I guess, emotions and just wanting to help and want to do something for their country.”

The three men joined the Royal Rifles of Canada and were sent to Hong Kong. Paul Martin may have died during the battle. According to historian Tony Banham in his book Not the Slightest Chance (2003), Paul Martin was among the 39 soldiers who died during the assaults on Stanley Mound and Stone Hill on December 22. He probably died at the same time as the Acorn cousins, but few details exist beyond this information.

The survivors of the battle were taken and held prisoner by the Japanese until the war ended in 1945. Most soldiers returned home with many scars from the atrocious conditions in the camps and abuse by the guards. Ivan Gray mentioned that his grandfather contracted malaria and died at the age of 55 of an aneurysm. Gray thinks that this illness could have been caused by some trauma that his grandfather sustained during his imprisonment.

Back Home

Medical institutions at the time did not recognize post-traumatic stress disorder, and many veterans of the war and camps received little care for these mental health conditions. Some men resorted to self-medicating with alcohol and drugs to quell their personal demons. Patrick Metallic, unfortunately, was one of these men. Ivan Gray reported that his grandfather would sometimes have attacks and wake up in a panic.

While Canadian soldiers received benefits for their service, Indigenous veterans were denied these rights, and the benefits were refused to most for discriminatory reasons. Very few Indigenous veterans received the pensions they were promised or any financial compensation. The military bureaucracy did not work in favour of Indigenous veterans. While their Canadian comrades were under the responsibility of the Department of Veterans Affairs, which was created in 1944, Indigenous veterans did not fall under this department’s responsibility. The management of Indigenous peoples on Canadian soil varied from one part of the government to another; for example, from 1936 to 1950, the Department of Mines and Resources was responsible for Indigenous Affairs. From 1966 to 2019, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development oversaw veteran issues. However, officials in this department were ill-equipped to deliver the compensation deserved by Indigenous veterans, few of whom received what they should have for their services.

The relationship between Canada and the Indigenous communities within its borders has been fraught, to say the least. For many reasons, the role of Indigenous soldiers has long been overshadowed and under-recognized in our national memory. Although a national monument was put up in Ottawa in 2001 to honour Indigenous veterans from the World Wars and the Korean War, little has been done to redress the many wrongs against them. These people served their country, but it took a long time for their service to be recognized.

Cover photo: Mi’kmaq soldier Paul Martin of the Listuguj Reserve. Martin was one of the indigenous soldiers who died during the Battle of Hong Kong.

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens, with edits by Joel Beauchamp-Monfette and Simon Berger. Translation by Amy Butcher (www.traductionsamyb.ca). Re-printed here with the permission of Quebec Heritage News as part of a collaboration between JMS and QHN. The article is already available in the Spring 2022 issue of QHN and available here. To see more articles like this one, check out their archive.

Sources:

- “ACORN John Murdock – F/40906 (NA)“, Military Database Project.

- “Indigenous Peoples and the Second World War“, L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- “Indigenous People in the Second World War“, Anciens combattants Canada/Veterans Affairs Canada.

- “Indigenous Soldiers – Foreign Battlefields“, Anciens combattants Canada/Veterans Affairs Canada.

- “Indigenous Veterans: Equals on the Battlefields, But Not at Home“, Indigenous Corporate Training Inc.

- “Individual Report: E30097 Patrick METALLIC“, Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association.

- “National Aboriginal Veterans Monument“, Anciens combattants Canada/Veterans Affairs Canada.

- “Remembering a Mi’kmaw soldier who spent years as a prisoner of war“, CBC.