THE WAR IS OVER!

The belief that the First World War would be “the war to end all wars” prompted the Allies and their supporters to redouble their efforts, despite their immense losses. The Armistice was declared on November 11, 1918, at 11:00 a.m. By the end of the war a staggering number of lives had been lost: more than 20 million civilians and 9 million soldiers. The old world no longer existed and, despite the new frontiers and the emergence of victorious nations, peace was not guaranteed. The League of Nations (which would eventually become the United Nations) was unable to prevent the horrors of the Second World War.

Canada, having proved itself in the First World War, gained control over its external affairs, its commitment to Britain’s foreign policies and decisions to enter into war. Political power struggles over Canada’s internal and external affairs also led to aggressive international policies that concerned the definition of Canadian values, its founding French and English cultures, new Canadians, and the establishment of new rights for women and workers.

Despite the victory and despite the war being over, many continued to suffer from illness and psychological scars. The path to reconciliation spanned generations. We must still ask ourselves today what we have learned from the First World War. Were human sacrifices necessary to move Canada forward on the world stage and make Canada the country it is today? Was it worth it?

Coming back wounded

Known as the ‘’broken gargoyles’’, many men came back from the front wearing the consequence of the war on their faces and bodies. Disfigurement and broken limbs were an important post-war issue as 172,000 Canadian soldiers were reported wounded during the war (approximately 40% of all those who served overseas). These injuries brought serious problems when trying to reintegrate society: difficulty to find a job, social isolation, lost of identity and pride, difficulty finding a life partner, alcoholism, and even suicide.

However, on a positive note, in an attempt to help veterans with social reintegration and provide a better life to the wounded, the years following World War I saw a rapid development of modern plastic surgery and prosthetics.

Facial reconstruction

Seeing the disastrous effects of shrapnels of soldiers faces, Sir Harold Gilles, an officer of the Red Cross from New Zealand, became the driven force of innovation in reconstructive surgery in the Commonwealth. He would treat and experiment in the Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sicup, near London, England, a hospital that specialized in facial wounds.

Masks

In certain cases, men with facial injuries were provided with prosthetic attachments held by straps or incorporated in eyeglasses. These would fully cover the wounds and sometimes based on pre-war portraits of the soldiers. The masks were made from copper or tin, and were painted to match patient’s skin color.

Artificial arms

Prosthetic arms greatly improved after the high demand of wounded veterans returning home with missing arms. Usually made of wood, leather, rawhide and metal, they were considered functional. Most models had interchangeable parts and moveable joints that the user could modify depending of the usage requirements. For example, the user could go from a wooden hand to resemble the allure of a natural arm to a hook to facilitate his task in a work environment.

Artificial legs

The prosthetics legs made after World War I were more efficient than earlier models, but also lighter. Manufacturers replaced traditional materials such as wood and steel to favour aluminium. They also added padding to make the devices more comfortable. To serve the high number of war amputees, the production of prosthetics shifted from being individually custom made to an industrial scale.

Hearing loss

The constant firing of rifles & machine guns, coupled with the explosions of artillery, grenades, and mortars made the trenches a particularly loud environment. During an artillery bombardment the noise on the battlefield could easily reach 140dB for extended periods. Various degrees of hearing damage were recorded within the ranks of the Canadian expeditionary force but the artillerymen suffered the most, firing large guns repeatedly for hours each day, every day.

Less visible wounds

Men returning to the civilian life were also prone to illness due to the long exposure of the harsh and unsanitary conditions of the trenches. Many suffered from chronic pains, tuberculosis, pulmonary problems, and in some case some had contracted a venereal disease.

War: A history of psychological trauma

After the war ended, those who survived the bullets, explosions, shrapnel, poisonous gas, infections from injuries, disease, and other battlefield hazards returned to civilian life. Though many came home with physical injuries, many also returned with far less apparent wounds: the psychological traumas of war. Although such conditions might be as old as war itself, the magnitude of modern combat set in motion a reflection on its effect on individuals.

1678

Diagnoses were given by the Swiss Army to soldiers displaying melancholia, disturbed sleep, anxiety, unwillingness to eat, fever and cardiac anomalies. Though with different names, this condition was being recorded around the world: as Heimweh in Germany, as Maladie du Pays in France or as Estar Roto in Spain.

1870s

Studied and reported by Jacob Mendes Da Costa after the American Civil War, “Soldier’s Heart” was a condition wherein the patient displayed persistent heart problems without physiological abnormalities.

1914

Soon after the first battles in the Great War, men with no physical injuries were seen to display medical symptoms (headaches, insomnia, tremors, amnesia, impairment of vision, etc). A large percentage of those injured in battle displayed these symptoms and were sent to field hospitals where they stayed until they were able to be reintegrated back into the battlefield.

1915

By 1915, the condition had a name used widely among the Allies: Shell Shock. Nonetheless, it remained poorly understood and was perceived negatively as a sign of cowardice. The German troops also experienced this war trauma; the condition was named Kriegszitterer, which translates to war tremors.

1939-1945

During World War II and, later, the Korean War, the terms combat exhaustion and combat fatigue were used to identify psychological war trauma. The more the condition was studied, the more it was taken seriously, and it became crucial to replace soldiers displaying symptoms in order to preserve unit cohesion.

1972

Many Vietnam War veterans were diagnosed with stress response syndrome in the United States of America. This also marked an important moment for psychological war trauma awareness as veterans started to protest for their mental health care and demanded that this illness be perceived as a normal reaction to witnessing atrocities, rather than as a sign of mental weakness.

1980

The illness was reclassified under post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and gained the definition that we know today. PTSD is now recognized as a mental illness that involves a traumatic experience. PTSD is not limited to combat experience because trauma can be caused by various experiences: crimes, natural disasters, accidents, sexual assaults and other stressful events.

Remembering

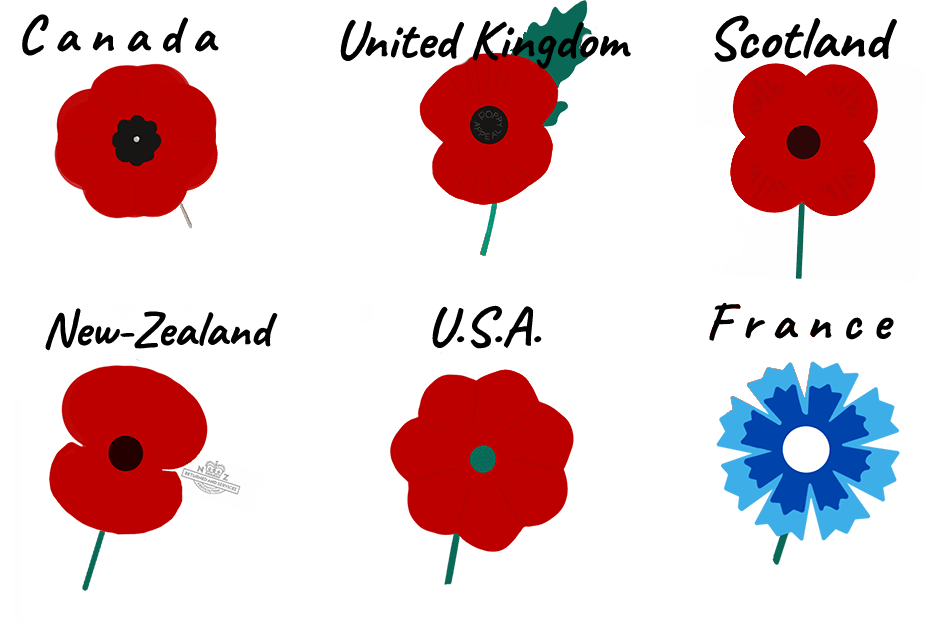

What’s a Poppy?

The papaver rhoeas, known as the common poppy, is an annual flower that blooms in late spring in Europe. The flower thrives when the soil is disturbed. Due of the continuous bombardments in Belgium and other battlefields, the red poppies were a prominent feature near the trenches and over the soldier’s graves.

Did you know that the pollen of papaver rhoeas cause no allergic reaction via inhalation?

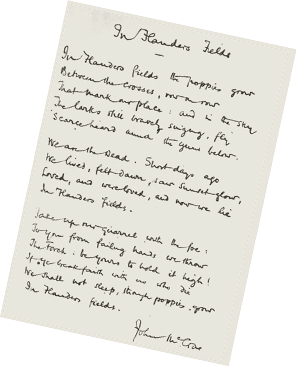

John McCrae’s Poem. May 1915

Inspired by the sight of the poppies, Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, a Canadian Medical Officer, wrote a short poem during the Second Battle of Ypres soon after the death of a close friend. McCrae was not very proud of his poem but was encouraged by friends to send it for publication.

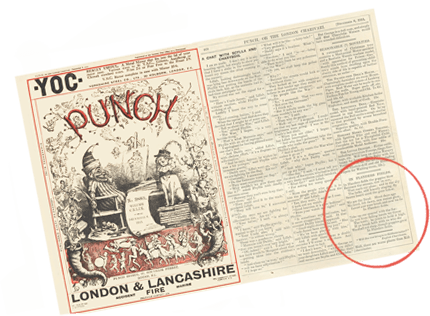

Punch Magazine, December 1915

Punch, or the London Charivari was a British satirical publication focused on short articles, poems and small print. Prior the war, Punch was a well-established and very popular magazine. In December 1915, they decided to publish John McCrae’s 13 lines poem.

Did you know that Punch Magazine published anti-war content prior to World War I? Quickly after the beginning of the conflict, the magazine did not publish anti-war statement and became very supportive of the war effort.

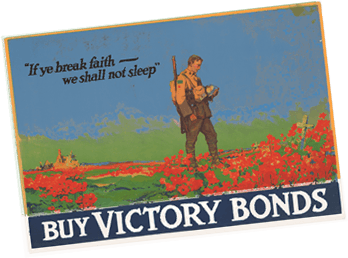

Recruitment tool, 1917

John McCrae’s poem along with the poppies were often used in propaganda posters to sell war bonds and for the recruitment effort. This was especially true in Canada as the country was going through the conscription crisis and needed a symbol of perseverance.

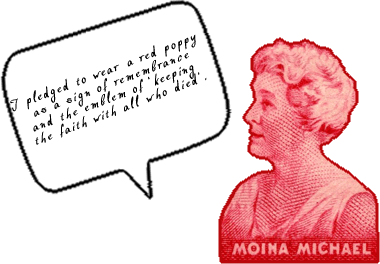

Moina Michael, 1918

An American teacher, miss Moina Michael was touched by reading John McCrae’s poem and vowed to wear a red poppy as a remembrance symbol for those who served during the War of 1914-18. As she was teaching wounded veterans at the University of Georgia at the time, she realized there was a financial need to support these men, and so she started raising funds by selling silk poppies.

Madame Anna Guerin was inspired by this initiative during a visit to the United States and brought the idea to France, and she drove multiple campaigns to help widows and orphans of the war.

Veterans’ Associations, 1921

The ancestor of the Royal Canadian Legion, the Great War Veterans’ Association in Canada made the poppy their official remembrance symbol in July 1921. The same year, the Royal British Legion ordered 9 million poppies in the hope to sell them on Armistice Day (11 November). In both countries the poppy campaign was a success and the profits went to support veterans of the war.

White Poppy, 1926

After the popularization of the red poppy in the Commonwealth, pacifist movements in the United Kingdom started to use a white version of the traditional remembrance poppy to add the hope of a world without war. Today, many anti-war organizations support the White Poppy Movement but it’s popularity has diminished by the controversy surrounding the meaning of the white poppy, which is perceived as a lack of respect for the veterans and those who paid the ultimate sacrifice.

Today

Red poppies are worn on lapels every year in Canada from the last Friday in October until November 11th to remember those who died in combat, and not exclusively during World War I. They can be procured from the Legion during this period in exchange of a donation to help support veterans. Poppy Appeal Campaigns are usually the biggest fundraising activities of Legion organizations. Based on an act of parliament on 30 June 1948, only the Legion has the authority to sell poppies, “entrusted by the people of Canada to uphold and maintain the Poppy as a symbol reminding us to never forget the sacrifices Veterans made to protect our freedom.”

Additional resources

For your research:

Government of Canada Service Files for WWI (personnel records)

https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/personnel-records/Pages/search.aspx

Veterans Affairs Canada- Book of Remembrance

http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/books/search

Circumstances of death registers- WWI- Library and Archives Canada

http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/mass-digitized-archives/circumstances-death-registers/pages/circumstances-death-registers.aspx

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

https://www.cwgc.org/

Multimedia material:

Armistice Celebrations: New York, Paris, London, 15:18 mins

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pqgnSXwPfCw

Treaty of Versailles and German responsibilities end of WWI, The Telegraph, 1:35 mins

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/germany/8029948/First-World-War-officially-ends.html