Thousands of French Canadians served in the Canadian Army during World War II. Among them, many were mobilized into Force C: the Canadian force sent to defend the British colony of Hong Kong. In this short article, discover Quebec’s baptism of fire during the war!

Quebec’s school curriculum tends to summarize French Canadians’ participation in World War II as the 1944 conscription crisis, with occasional mentions of the Normandy landings and the liberation of the Netherlands. However, very few know the extensive participation of some 160,000 French Canadians who voluntarily enlisted in the army.

Very few people in Quebec know, for example, that the province’s first involvement in World War II was on December 8, 1941, during the Battle of Hong Kong. Although it was not an officially French-speaking unit, nearly one-third of the members of the Royal Rifles of Canada were French-speaking.

The Royal Rifles of Canada

The Royal Rifles of Canada were based in Quebec City and trace their origins back to 1862. Their reputation was already well established in the Canadian military even before the Battle of Hong Kong, as this long-standing regiment had been deployed during the Second Boer War (1899-1902) and the First World War (1914-1918). In 1939, the Royal Rifles were called back into active service. Like many other regiments at the time, in the aftermath of the interwar period, the Royal Rifles faced several challenges in terms of recruitment and equipment supply. To compensate for the shortage of men, on July 20, 1940, more than half of the officers and soldiers of the 7th/11th Hussars (a young armored unit based in Sherbrooke) were transferred to the Royal Rifles.

Unlike the other regiments mentioned above, the Royal Rifles of Canada was not entirely made up of Francophones. Although based near Quebec City, the regiment was officially Anglophone. Yet it did attract many Francophones from the surrounding areas, who made up almost half the regiment at about 40% or so of its strength. Its young soldiers included Jean Leblanc from New Richmond, Quebec, who joined the army in 1940 at the age of 16, and Bernard Castonguay, who was originally from Montreal but who also went to Quebec City to join the regiment.

The language used by the Canadian army at the time was English, even in French-speaking regiments! However, the soldiers easily understood orders and often translated them into French, as Lucien Dumais of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal explained: “You’ll no doubt notice how I often say ‘Monsieur,’ at the beginning, in the middle and even at the end of sentences when conversing with the colonel. This is a translation of the English ‘Sir’ that English-speaking Canadian soldiers got from the British” (Lucien Dumais, 1968, p. 94).

This was also not a major problem for the Royal Rifles of Canada, as many volunteers were already bilingual when they enlisted. Therefore, for many Francophones, English was the language they used for both their training and missions.

In Hong Kong

The Royal Rifles of Canada landed in Hong Kong in November 1941 with the rest of “C” Force. At the risk of stating the obvious, the experience of French-speaking soldiers there was no different from that of English-speaking soldiers. Indeed, Like any other soldier, whether English-speaking, British, Chinese, or Indian, the Francophone soldiers were no less involved in the fray against the Japanese army during its invasion of the colony in December 1941.

The Japanese first captured the Kowloon Peninsula, before reaching Hong Kong Island a few days later. It was there that the Royal Rifles took part in combat for the first time. As a signaller, Bernard Castonguay was one of the first to hear the Japanese arriving. In an interview in English, he said:

“[…] And really that was quite a shock. The first bomb that fell close to me by planes, that was really something but after that I was not nervous at all. It could come.” (source).

This first wave of bombing claimed one of the first Quebecois victims of the war: Officer Albert Bilodeau. From Richelieu, the sergeant in Company C was wounded by a bomb. Fortunately, he survived the battle, but was ultimately captured by the Japanese, along with the rest of his regiment.

The Allies are quickly overwhelmed by the Japanese army after landing on the island. However, the Royal Rifles were some of the last to fight in Hong Kong, which meant that several French-speaking soldiers were among the final resisters during the final assault on Stanley Village. The battle ultimately ended in tragic defeat, with all of the defenders being taken prisoner until the end of the war.

The Japanese made no distinction between Francophone and Anglophone soldiers and put them together at the camps, where they all experienced the same appalling conditions. The only difference was that the Francophone soldiers had to communicate with their families in English, as the Japanese lacked the resources to read each letter in French to ensure the missives did not contain compromising information.

In any case, communication was poor. Bernard Castonguay’s family had no news about him for almost two years, save for some letters from the government or newspaper articles. It wasn’t until September 11, 1943, that Castonguay’s family received a first letter written by him… dated May 31, 1942!

Conclusion

Finally, the war ended for them in August 1945 with Japan’s surrender. The French Canadians were thus able to return home. But what about their legacy? Most of the French-speaking regiments still exist and continue to celebrate their military achievements, perpetuating the memory of veterans who are now gone. However, the Royal Rifles of Canada were disbanded in 1966. Although, due to their transfer in 1940, the Sherbrooke Hussars now wear the Royal Rifles badge with the year 1941 on their uniforms in their honor, this significant participation of French-speaking soldiers from Quebec is still largely unknown.

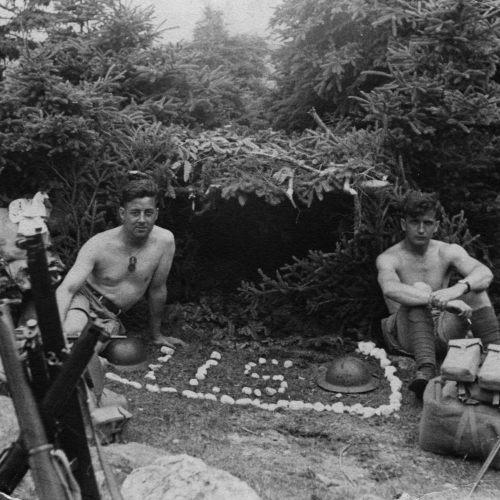

Cover photo: Lauréat Bacon (left) and a comrade training in Newfoundland (source: Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association). View his file here.

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (www.traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- “Individual Report: E30659 Bernard CASTONGUAY“, Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association.

- “Le Canada et la guerre – Les unités francophones“, Musée canadien de la guerre/Canadian War Museum (in french).

- “Military“, Gouvernement du Canada/Government of Canada.

In 2024, Julien published a scientific article on the memorial treatment of the Battle of Hong Kong in Quebec. You can read it for free right here:

- Julien Lehoux, “« Souvenons-nous de Hong Kong » : la bataille de Hong Kong et son absence mémorielle au Québec de 1941 à aujourd’hui“, Études Canadiennes/Canadian Studies, vol. 97, 2024, pp. 35-60 (in french).

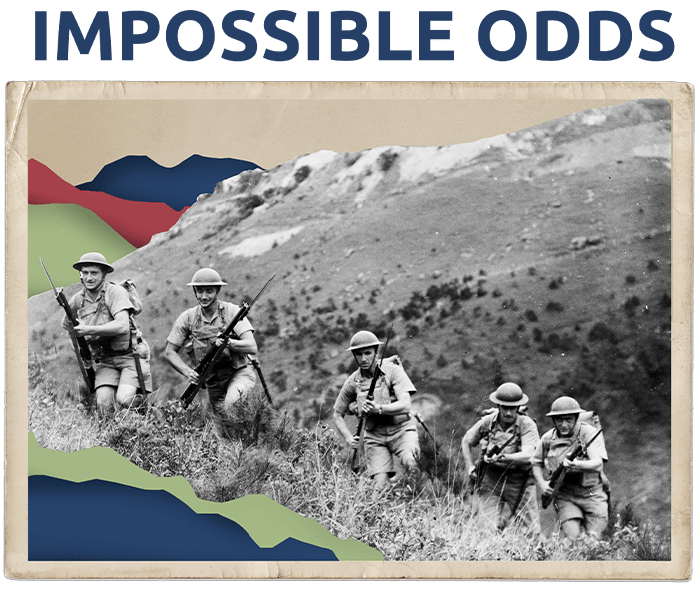

This article was published as part of our exhibition on the Battle of Hong Kong: Impossible Odds. Visit our exhibition to learn more about the history of the Canadian who defended the colony of Hong Kong!