This article was published as part of our exhibition on the Battle of Hong Kong: Impossible Odds.

Visit our exhibit to learn more about the fate of the Canadian soldiers sent to defend the colony!

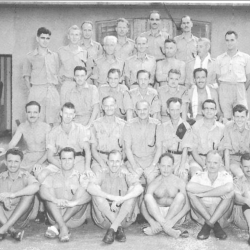

Four POW camps were set up in the former British colony: Ma Tau Chung, Argyle Street, North Point and Sham Shui Po. Ma Tau Chung was a camp for “undesirables,” or Indian soldiers who refused to join the Japanese army, as well as marginalized people who were undocumented or had no legal status. The camp on Argyle Street was initially for British, Canadian and Indian soldiers, but it was later reserved for officers starting in 1942. North Point and Sham Shui Po received the most captured Canadians during the war.

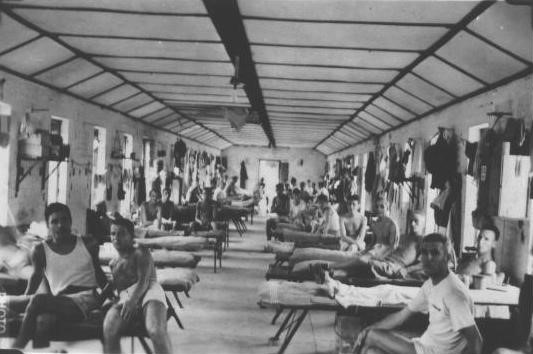

Conditions in the camps

All buildings at the camps were badly damaged from the fighting: their roofs and walls were riddled with shell holes and did not provide adequate shelter for the new prisoners. These paltry wooden abodes were crammed with men and could house up to 175 prisoners. The kitchens and health and hygiene facilities were also in a pitiful state. When the Canadian, British and Indian prisoners arrived at North Point, they did their best to make the camp habitable, but it took time. For example, the camp’s two latrines were only set up on February 2, 1942.

All camps had very poor-quality food that often consisted of white rice laced with sand, old vegetables or rotten meat. The rations are very small, and the prisoners lost dramatic amounts of weight. From December 25 to January 15, some prisoners lost up to 10 kilos! The low vitamin and protein diet gave rise to a host of diseases such as “burning feet” syndrome, beriberi and pellagra. A hospital was set up in the North Point camp, but it had very few beds or medical supplies. Given its leaky roof, patients might lie in an inch of water on the floor during rainy periods.

Some prisoners in Hong Kong were forced into labour and had to rebuild the Kai Tak airport. Their task was to remove an ancient burial hill using only shovels and traditional baskets suspended from a pole and balanced on their bony shoulders. Many men could not do the work, especially because they were chronically malnourished. Conditions at the different sites frequently included brutal treatment, and Canadians reported many abuses. For example, guards often rifle-butted their inmates, breaking their bones and teeth. Slapping and humiliation were also common practices. For example, Japanese guards would tie prisoners naked to stakes for hours or days in all types of weather. As the prisoners were already in poor health, many did not survive the ordeal.

Stanley Internment Camp

The Stanley internment camp was created in January 1942 to house Japan’s entire civilian “enemy” population, i.e., the British, Americans, Dutch and Canadians. Whole families were sent to this camp, whose conditions were no different from those of the military camps: the food was poor and in short supply, the buildings were damaged and overcrowded, and disease was rampant. The 2,800 civilians at this camp included 73 Canadian men and women, who were detained there until their repatriation in September 1943. However, the majority of those interned had to wait until the end of the war to be released.

Transfers to Japan

Starting in the middle of 1942, there were four prisoner transfers from Hong Kong to Japan that included Canadians. This came after two transfers of British prisoners: the first included about 650 men in September 1942 and the second had 1,800 at the end of the same month. Unfortunately, the second cohort had embarked on the Lisbon Maru, which was sunk by accident by an American submarine. Out of the over 1800 captives on board, 843 died in the catastrophe.

Bernard Castonguay and his companions were sent to Japan on January 19, 1943. The men were packed so close together that they couldn’t lie down at the same time. They had nothing to eat or drink during the whole trip save for some small rice balls and water. The air quickly became foul in part from the stench of hundreds of men sweating in the extremely hot temperatures in the ship holds, which had no air circulation. Many of the prisoners suffered from dysentery and diarrhea and had no access to latrines on the boats. Despite the tragedy of the Lisbon Maru, the Japanese did not provide life jackets for the POWs.

As the war progressed, the travel conditions deteriorated even more. The journeys generally became longer, more poorly supplied, and so overcrowded that the men arrived in Japan much sicker and less fit than when they had started the trip. Overall, about 1,100 Canadians were transferred to Japan during the war.

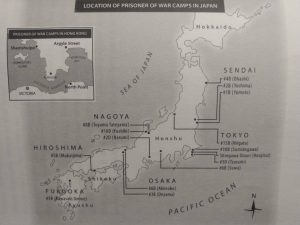

The Japanese Camps

Living conditions at the camps in Japan were much the same as in Hong Kong, with the same problems of discomfort, lack of food and disease. In some camps further north, the prisoners also had to deal with colder weather and harsher winters, which brought on a whole other set of problems.

The camps in Japan were mostly labour camps to support the war effort. While the Canadians had a small chance to avoid hard labour in Hong Kong thanks to different strategies, they could not do so in Japan. All prisoners were subjected to forced labour under extremely difficult conditions. Accidents were frequent and abuse was common.

There were many more camps in Japan than in Hong Kong, and here are the ones that housed Canadian prisoners:

Niigata 5B and Niigata 15D/15B: These camps were located in the small coastal town of Niigata. About 500 prisoners (200 Canadians and 300 Americans) worked at the Rinko coal mines, the Marutsu shipyard, or the Shintetsu iron foundry. Copper was also mined in the area. The men there suffered from malnutrition and avitaminosis. The most common symptoms were beriberi and edema. The malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies affecting most prisoners were aggravated by illness, poor living conditions, and intense physical labour.

Sendai 2B: This camp’s first 200 prisoners arrived in May 1944, and they were forced to work in the coal mines of the Furukawa company. Work in the mines was hard, and food was lacking. The prisoners could wear only a fundoshi—the traditional Japanese loincloth—and what were termed “hard hats” but which were actually cotton hats lined with pieces of felt.

Oeyama (Osaka No. 3): Oeyama is a village on the northwest coast of the island of Honshu. At the camp, enlisted men worked in the nickel mines or at the refinery, while officers were assigned moderately heavy duties. This camp had 148 Canadians in September 1944.

Ohasi: In April 1945, 200 Canadians were transferred to this camp in northern Japan. They worked on motors, generators and electric trains. The conditions were harsh, but some said that the Japanese treated the prisoners under their command very well.

Omine: Located near the small town of Kawasaki, this camp held 163 Canadian and 37 British POWs. The prisoners had to mine coal for the Furukawa Mining Company. The quarters were better than at most camps, but the working conditions were still grim. Food was insufficient in quality and quantity, and disease was incessant.

Omori: This camp, located on a small sandy island in Tokyo Bay, was a disciplinary camp where “bad interns” were sent. The prisoners there worked as handlers at the cargo terminals and shipyards in Tokyo and Yokohama. Some groups worked at the Mitsubishi warehouses and others unloaded tobacco at railroad stations.

Narumi (Fukuoka No. 2): This camp was located a few kilometres from downtown Nagoya. The men there worked in a factory that made locomotive engines, but many others were transferred to factories for airplanes and war ships. Given its proximity to Nagoya, which was heavily bombed, many of the camp’s detainees were moved in spring 1945.

Tsurumi (Tokyo 3D, Kawasaki): A camp located in the western suburbs of Tokyo that housed 500 prisoners in early 1943. Most men worked at the Nihon Kokan Shipbuilding Yard, where they did a variety of jobs: painting, work with oxygen tanks, ironwork, work with chisels and other tools, etc. In 1943, sixty-three Canadians died from diseases brought on by malnutrition, overwork or accidents at the unsafe mines, factories and shipyards

This work was gruelling, and many Canadians died in captivity. Finally, Japan signed its surrender in August 1945 and the war ended for good. A few weeks later, the Canadian prisoners in Hong Kong and Japan were repatriated. However, the road back was long, and most men had to spend weeks in recovery. Many came out of these camps with tremendous physical and psychological scars that would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens with notes provided by Flavie Vaudry. Translated by Amy Butcher (www.traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- “Canadians in Hong Kong“, Anciens combattants Canada/Veterans Affairs Canada.

- “Canada and the Battle of Hong Kong“, L’Encyclopédie Canadienne/The Canadian Encyclopedia.

The Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association website also has many stories and testimonials about the imprisonment of Canadian soldiers in Hong Kong and Japan. For a more academic approach, we suggest the following books:

- Tony Banham, The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain’s Forgotten Wartime Tragedy, Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 2006, 342 p.

- Tony Banham, We Shall Suffer There: Hong Kong’s Defenders Imprisoned, 1942-45, Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 2017, 260 p.

- Geoffrey Charles Emerson, Hong Kong Internment, 1942-1945: Life in the Japanese Civilian Camp at Stanley, Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 2008, 268 p.

- Nathan M. Greenfield, The Damned: The Canadians at the Battle of Hong Kong and the POW Experience, 1941-45, Toronto, Harper Collins Publishes, 2010, 462 p.

- Charles G. Roland, Long Night’s Journey into Day. Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941-1945, Waterloo, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2001, 449 p.