This article was published as part of our Dieppe Raid exhibit: Courage in Chaos.

View our exhibit to learn more about the sacrifice of the Canadian soldiers sent to attack the beaches of Dieppe!

As mentioned in our previous article, Canadian soldiers underwent strenuous training when they arrived in the British Isles in December 1939. However, they also had to deal with a lot of downtime. They did everything they could to mark off the days, whether through hobbies or other attempts to escape the boredom of the training camps.

Any Entertainment Was Good Entertainment

Fortunately for the garrisoned Canadians, the camps were often located near major British cities. Although London was supposed to be off limits due to ongoing German attacks, the city was a regular destination for soldiers from the surrounding area. The British capital was an appealing attraction with lively streets the men could stroll down.

Besides walking around the city, the men often went to the nearest movie theatre to watch the latest movies. Many cinemas and theatres were also set up at the camps themselves to entertain the soldiers. André Vennat of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal described how he went to the movies about twice a week, as there were two theatres near where he was stationed.

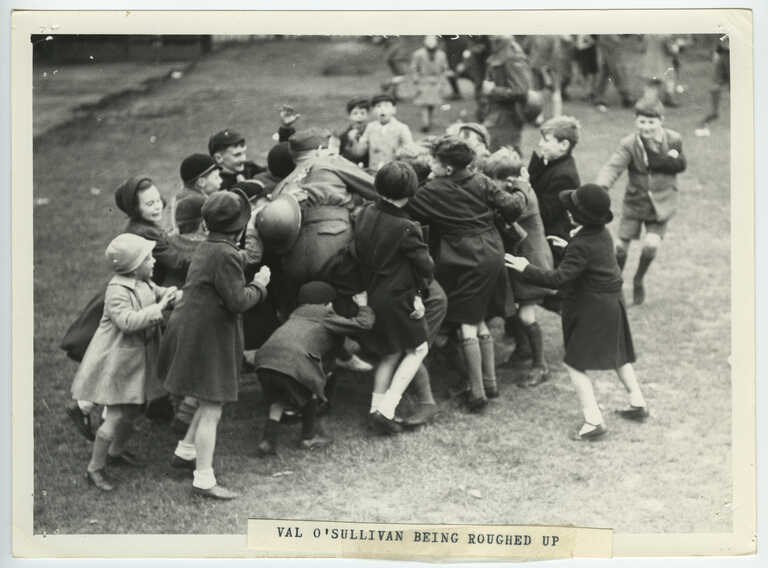

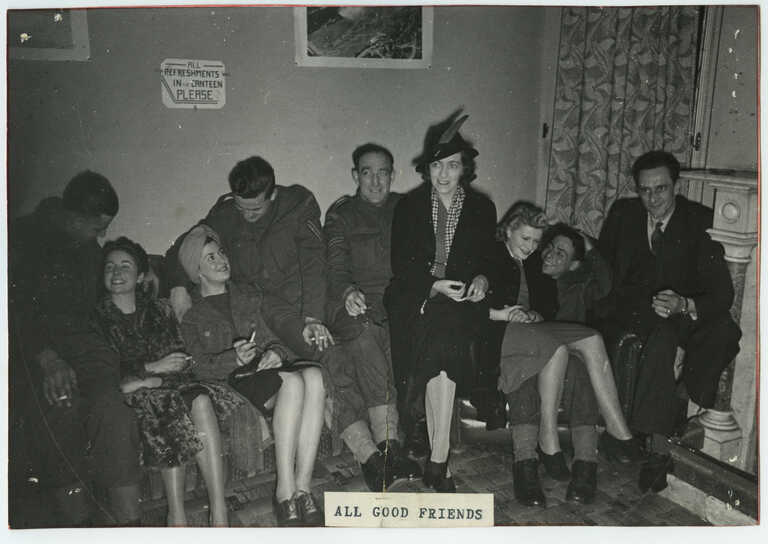

Naturally, the soldiers socialized with British civilians. Private Jacques Nadeau, who was also a member of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal, described how he learned English from a family living near his camp. Many social events were also organized between the soldiers and British military and civilian women. For example, in the London borough of Sutton, the “Montreal House” held many social evenings for the soldiers of the Royal Montreal Regiment and local women. Engagements and weddings were frequent. Jacques Nadeau said that he became engaged twice during his time in the garrison: “You were engaged to a girl as soon as you dated her more than once. The word described just as much a relationship with a stable friend as someone you hoped to marry.” (Martin Chaput, Dieppe, ma prison. Récit de guerre de Jacques Nadeau, Montreal, Athéna Éditions, 2008, pp. 38-39).

The Heavy Toll of Boredom

Garrison life could be very monotonous. Boredom always loomed whenever the soldiers weren’t training or spending time on hobbies. As mentioned, the first Canadian troops went to Britain in 1939 and they had to wait almost two years before Operation Jubilee. For these soldiers itching to see action, the almost two-year wait seemed interminable.

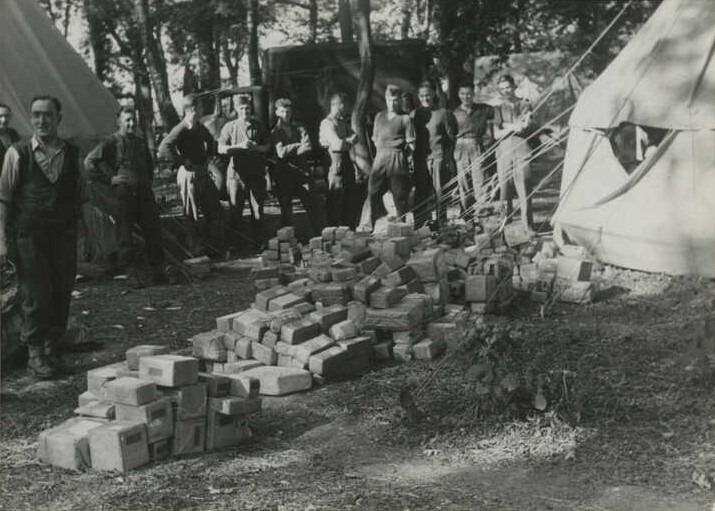

Many soldiers found work as a good way to pass the time. Jacques Nadeau said that he and a friend took on a construction job that lasted several months just to get the chance to leave the camp. In letters sent to his wife (compiled by his son Pierre Vennat), André Vennat went on at length about his boredom in the garrison. He said that the days were long and that he wasn’t interested in the few types of entertainment that were available. Only his daily tasks and classes helped alleviate the tedium. As he wrote to his wife, “The most important thing is to have something to occupy my time, and that’s good, because sometimes I get so bored that I don’t want to do anything.” (Pierre Vennat, Dieppe n’aurait pas dû avoir lieu, Montreal, Éditions du Méridien, 1991, p. 116).

As shown by André Vennat’s many letters to his wife, communicating back home was particularly important for the garrisoned soldiers. When they had time, the soldiers would write many letters to their families and friends in Canada. As communication systems were not like they are today, it could take many days for soldiers to get the great joy of hearing back from their loved ones.

Mission: Distraction

Overall, the days in Britain could be very long for these men who were anxious to join the fighting. Finding ways to amuse themselves was important, especially considering the rigorous training they went through. Boredom was a terrible punishment for these soldiers with too much time on their hands.

Cover photo: Couples recently married in Britain on their way back to Montreal (source: Royal Montreal Regiment Museum collection).

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

For this article, we recommend that you read the books by Martin Chaput and André Vernat (both in French), referenced here several times, to learn more about garrison life in Britain:

- Martin Chaput, Dieppe, ma prison. Récit de guerre de Jacques Nadeau, Montréal, Athéna Éditions, 2008, 140 p.

- Pierre Vennat, Dieppe n’aurait pas dû avoir lieu, Montréal, Éditions du Méridien, 1991, 199 p.

The Royal Montreal Regiment Museum also has several online photos from its collection showing the daily life of the soldiers there that can be viewed at this link.