This article was published as part of our exhibition on the Battle of Hong Kong: Impossible Odds.

Visit our exhibit to learn more about the fate of the Canadian soldiers sent to defend the colony!

Quebec’s school curriculum tends to only make quick mention of how French Canadians participated in the Second World War during the Conscription Crisis of 1944. While many people may recognize the names and heroism of soldiers like Léo Major and Lucien Dumais, very few know the particulars of how Quebec and French Canadians became involved in the conflict. In fact, over 160,000 voluntarily enlisted in the army during the war.

The province had four fully Francophone regiments at the time: Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal (Montreal), Le Régiment de Maisonneuve (Montreal), Le Régiment de la Chaudière (Lévis) and the Royal 22nd Regiment (Quebec City). These military units were mobilized in Europe and saw action during the war, with Le Régiment de la Chaudière participating in the famous Normandy landings in June 1944. However, other regiments also had French Canadians in their ranks, such as the Royal Rifles of Canada, which was sent to Hong Kong in 1941.

The Royal Rifles of Canada

In recent articles, we described the role of the Royal Rifles of Canada in Hong Kong as part of C Force. However, their reputation was well established in the Canadian military even before Hong Kong, as this long-standing regiment had been deployed during the Second Boer War (1899-1902) and the First World War (1914-1918).

Unlike the other regiments mentioned above, the Royal Rifles of Canada was not entirely made up of Francophones. Although based near Quebec City, the regiment was officially Anglophone. Yet it did attract many Francophones from the surrounding areas, who made up almost half the regiment at about 40% or so of its strength. Its young soldiers included Jean Leblanc from New Richmond, Quebec, who joined the army in 1940 at the age of 16, and Bernard Castonguay, who was originally from Montreal but who also went to Quebec City to join the regiment.

The language used by the Canadian army at the time was English, even in French-speaking regiments. However, the soldiers easily understood orders and often translated them into French, as Lucien Dumais of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal explained: “You’ll no doubt notice how I often say ‘Monsieur,’ at the beginning, in the middle and even at the end of sentences when conversing with the colonel. This is a translation of the English ‘Sir’ that English-speaking Canadian soldiers got from the British” (Lucien Dumais, 1968, p. 94). This was also not a problem for the Royal Rifles of Canada, as many volunteers were already bilingual when they enlisted. For many Francophones, English was the language they used for both their training and missions.

In Hong Kong

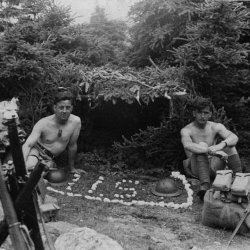

The Royal Rifles of Canada landed in Hong Kong in November 1941 with the rest of C Force, and the Francophone soldiers were no less involved in the fray against the Japanese army during its invasion of the colony in December 1941. As a signaller, Bernard Castonguay was one of the first to hear the Japanese arriving. In an interview in English, he said: “[…] And really that was quite a shock. The first bomb that fell close to me by planes, that was really something but after that I was not nervous at all. It could come.”

The Royal Rifles were some of the last to fight in Hong Kong, which meant that a number of French-speaking soldiers were among the resisters, as we saw in our article on the final assault on Stanley Village.

The Japanese made no distinction between Francophone and Anglophone soldiers and put them together at the camps, where they all experienced the same appalling conditions. The only difference was that the Francophone soldiers had to communicate with their families in English, as the Japanese lacked the resources to read each letter in French to ensure the missives did not contain compromising information. Bernard Castonguay’s family had no news about him for almost two years, save for some letters from the government or newspaper articles. It wasn’t until September 11, 1943 that Castonguay’s family received a first letter written by him, dated May 31, 1942.

When the war ended in August 1945 with the surrender of Japan, the French Canadians could finally return home. But what about their legacy? The Francophone regiments listed above exist today and continue to celebrate their comrades’ achievements. However, the Royal Rifles of Canada was reduced to nil strength in 1966. Although the Sherbrooke Hussars pay homage to the Royal Rifles by wearing its badge with the year 1941 on their uniforms, few people remember the tremendous contribution of Francophone soldiers from Quebec to the war effort.

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (www.traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- « Canada and the War – Francophone Units », Musée canadien de la guerre/Canadian War Museum.

- « Individual Report: E30659 Bernard CASTONGUAY », Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association.

- « La force francophone – Military », Gouvernement du Canada/Government of Canada.