This article was published as part of our exhibition on the Italian Campaign: Through Vines and Mines.

Visit our exhibition to learn more about the history of the Canadian soldiers and nurses sent to Italy!

When the Italian campaign began in September 1943, the majority of troops involved were American, British, Canadian, Indian and Sikh. The German and Italian defense was fierce, however, and as the campaign wore on, many other foreign forces were mobilized to support the Allied armies. Thus, in 1944, while the campaign was in full swing, Polish and French troops were sent into the fray.

As mentioned in our previous article, the Polish Army in the West was placed under the command of the British Army and acted as one of its branches, in the same way as the Canadian Army deployed in Italy. As for the French Expeditionary Corps, it acted more autonomously, but in collaboration with the American Army. Although both armies operated on their own side of the peninsula, it was during the Battle of Monte Cassino that they fought side by side.

The Polish Army in the West

History often tends to overshadow Poland’s military participation in the war. While its invasion by Nazi Germany is widely recognized as the event that triggered the conflict, very few people know that the Polish Army continued to fight throughout the rest of the war. Indeed, after taking part in its own way in the famous Dieppe Raid, several elements of the Polish Army of the West later found themselves in Italy.

The Polish Army of the West was formed immediately after the occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the exile of its government. Initially placed under the command of the French Army, the Polish forces were later reorganized under the British Army after the surrender of France in June 1940. The Polish Army then comprised three branches: navy, air force and army. While the first two were largely mobilized in the early years of the war, it was the army that constituted the main Polish force during the Italian Campaign.

In February 1944, the 2nd Polish Corps was sent to Italy to support the British and Canadians on the eastern flank of the peninsula. Formed the previous year, the 2nd Corps was mainly made up of experienced soldiers, veterans of fighting in Africa and the Middle East. By the time they arrived, the Polish presence in Italy had grown to over 50,000 soldiers… and a bear.

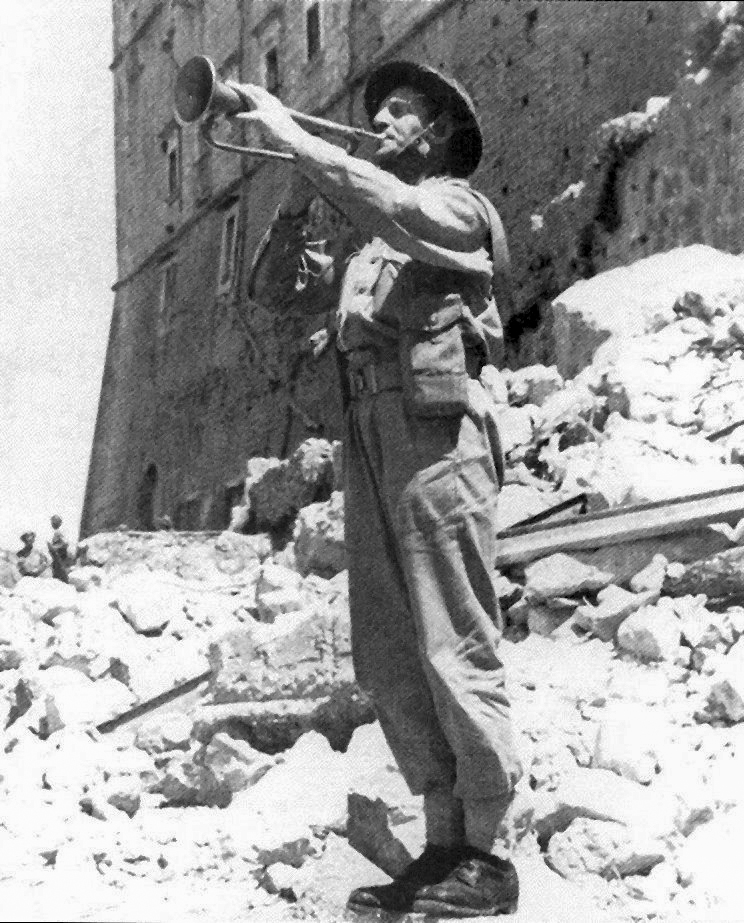

In Italy, the Polish Army particularly distinguished itself at the Battle of Monte Cassino. By this stage of the war, the battle had been underway since January 17, 1944, and the Germans were refusing to cede ground to the Allies. On May 11, 1944, Operation Diadem was launched in coordination with the American, British, Canadian, French and Polish armies, with the aim of dislodging the German defenders once and for all and opening a passage to Rome. During the battle, the 2nd Corps was tasked with capturing Monte Cassino. The fighting was extremely intense, and the Poles suffered heavy losses. At one point, the fighting even turned to hand-to-hand combat. Finally, after fierce fighting on May 17, the Germans were expelled from their position and the few remaining Polish soldiers captured the mountain. For the Poles, the battle came to a close the following day, when they captured the ruins of the Cassino monastery and the few German soldiers inside. It was a major capture, celebrated by the hoisting of the British and Polish flags.

Although the battle of Monte Cassino ended in victory, it came at a heavy price for the 2nd Corps, with a total of 3,885 casualties and 1,179 soldiers killed. Despite these sacrifices, the Poles remained committed until the end of the campaign, taking part in the autumn offensive and capturing the city of Bologna on April 21, 1945.

The French Expeditionary Corps

After its defeat at the hands of Germany in 1940, France found itself rapidly occupied, and was practically sidelined from the conflict. In Europe, however, resistance was alive and well, and several groups organized to hinder the Nazi forces as much as possible. France was also a major colonial power, and although some of its colonies sided with Germany and the Vichy regime in 1940, others joined the liberation forces under Generals Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud. Thus, between 1940 and 1944, France waged war on several fronts: at home, thanks to the Resistance, and abroad, with colonial troops.

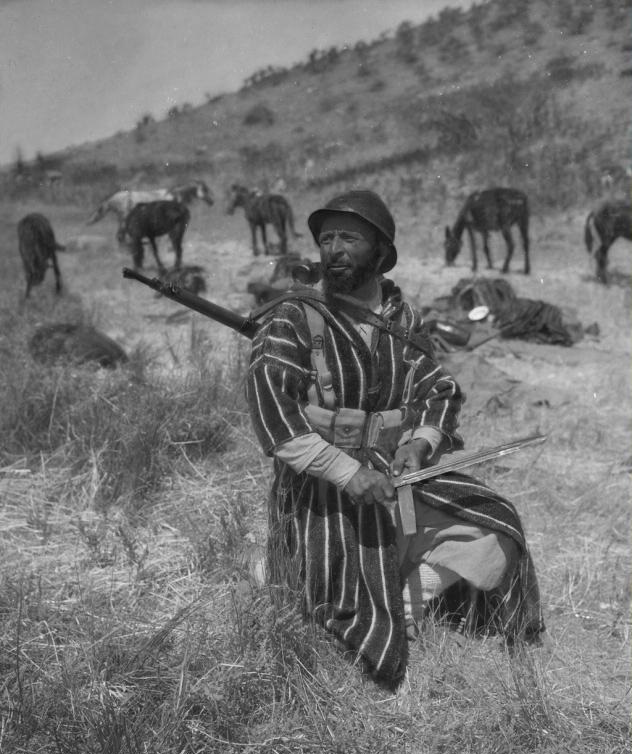

France’s participation in the Italian campaign began in 1943, after the Allies overthrew the Vichy regime. The result of the union of the forces of General de Gaulle and General Giraud that same year, the French Expeditionary Corps of Italy was sent to the peninsula in November to support the Allied effort in the campaign. Sending the Corps was a major undertaking for France, as between 95 and 112,000 troops, led by General Alphonse Juin, were mobilized in 1944. Most of the soldiers sent were from the French colonies in North Africa: Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. These troops were also joined by a number of French officers, in a structure typical of colonial armies. The Corps was then placed at the service of the American 5th Army.

As soon as they arrived, the troops of the French corps took part in various military operations alongside the other Allied armies. However, it was at the battle of Monte Cassino that France proved, according to historian Julie le Gac, that it had returned to the ranks of the great Allied powers. As explained above, Monte Cassino was a battle that had been bogged down for many months, and Allied losses were mounting. In preparation for a last-ditch effort in May 1944, General Juin persuaded the Allied General Staff to modify their strategy and give greater importance to the French Corps, so that it could surprise the Germans in an unexpected position. Juin’s plan was a success: on May 12, French and North African soldiers captured their objectives and supported British, Canadian and Indian soldiers. In fact, for two days, the colonial troops fought bravely and forced the German defenders to retreat on several fronts. The victory at Monte Cassino was not entirely due to the French army, but its contribution was certainly decisive.

Serious controversy marred French participation in the campaign, however. During operations, several units from colonial troops were accused of various abuses and agressions against civilian populations. War crimes are unfortunately a tragic consequence of war, and no army can claim to be immune from committing the worst abuses[1]. However, the actions committed by the soldiers of the French Corps were such as to tarnish an otherwise glorious operation. For many years, the controversies surrounding French participation in the Italian campaign overshadowed the sacrifices and successes made.

Conclusion

For Canada and its troops, the Italian Campaign was their first opportunity in the entire war to prove themselves as an independent nation. It is clear, however, that such a desire was also present among other foreign forces. For Indian and Sikh soldiers, their service in Italy enabled them to better assert their rights – or, at least, to better fight – for their countries’ independence. For Poland and France, Italy was a significant message that the humiliating defeats at the start of the war were not a sign of military incompetence. Finally, for Brazil, the campaign was an opportunity to show that it was a power equal to the western nations.

History has not always been kind to the Italian campaign. Overshadowed by the success of the Normandy and Provence landings, the efforts of one army or another in Italy have often been overlooked. Indeed, the campaign was long perceived as a secondary and unimportant front. However, a brief study of the various battles waged by the different Allied armies reveals a general determination to liberate the peninsula from Fascist and Nazi domination.

[1] Indeed, the Canadian Army was itself found guilty of war crimes in the destruction of the village of Friesoythe, Germany, on April 14, 1945. This attack took place after rumours circulated that a Canadian commander had been shot dead by a German civilian using a sniper rifle. In response, the Canadian Army expelled the town’s inhabitants and set fire to the houses. Although no civilians were murdered during the expulsions (although 20 deaths were recorded during the fighting the previous day), this episode nevertheless remains one of the Canadian Army’s most unfortunate during the war.

Cover photo: A Polish commando climbs a mountain in Italy in 1944 (source: Wiki Commons).

Article written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens.

Sources :

- “Free French Divisions“, Stone & Stone.

- “The battles of Monte Cassino and Belvedere“, Monte Cassino Belvedere.

- “The Polish II Corps in Italy“, Warfare History Network.

For a more academic approach:

- Julie Le Gac, “Le corps expéditionnaire français en Italie : un sacrifice inutile”, Jean Lopez & Olivier Wieviorka (dir.), Les mythes de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Tome 1, Paris, Perrin, 2018 [2015], pp. 277-290. To learn more, we also recommend her book Vaincre sans gloire – le corps expéditionnaire français en Italie (2013) (in french).